One of the main characters of M. Night Shyamalan’s Glass suffers from dissociative identity disorder. That illness is not shared by its director. Shyamalan may have his flaws, but he wields his camera with a confidence, a sense of self, that’s unusual in the Hollywood studio system. Good thing, too, because when reduced to its building blocks, Glass is a ridiculous movie, a bizarrely plotted thriller that makes astonishingly little sense. Yet it also flaunts a genuine personality, along with an exhilarating degree of style, that elevate it comfortably above its stupidity. There’s a school of critics who insist that Shyamalan should stop penning his own screenplays, arguing that his shaky writing hampers his gifts as a director. Maybe that’s true, but consider the flip side: How many other filmmakers could have taken this script and turned it into something so effortlessly, indecently entertaining?

An ungainly, tantalizing hybrid of two superior genre movies, Glass positions itself as the climax of a suddenly uncovered cinematic universe. Way back in 2000, Unbreakable—still Shyamalan’s best film—followed the uneasy partnership between David Dunn (Bruce Willis) and Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson), with the latter insistently tugging at the former to accept his destiny as a real-life superhero. Separately, Split followed the murderous exploits of Kevin Wendell Crumb (James McAvoy), a Sybil-like serial killer who occasionally transformed into a savage, animal-like entity called The Beast. Shyamalan is often accused of repeating himself, but these two movies weren’t remotely alike in terms of either plot or tone; Unbreakable was a powerful study of obsession, confusion, and self-discovery, whereas Split was a hammy, razor-sharp, predator-versus-prey thriller. Yet the (admittedly delightful) stinger of Split revealed that it in fact occupied the same world as Unbreakable, and from those still-glowing ashes, Glass was born.

The basic premise of Glass—take three larger-than-life characters, shove them into the same confined space, and let the machinations fly and the blood flow—carries a certain elemental appeal, not unlike that of the comic-book crossover. So it’s puzzling that Shyamalan insists on tamping down the film’s explosive potential for the better part of an hour. After conveniently assembling our mythological triumvirate in a Philadelphia mental institution—the kind with antiseptic hallways, weary security guards, and ominous storage rooms full of random bookshelves—the movie brings in Dr. Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulson), a psychiatrist who specializes in convincing people who think they’re superheroes that they’re really just suffering from delusions of grandeur. “It’s becoming more common these days,” she informs her mystified charges.

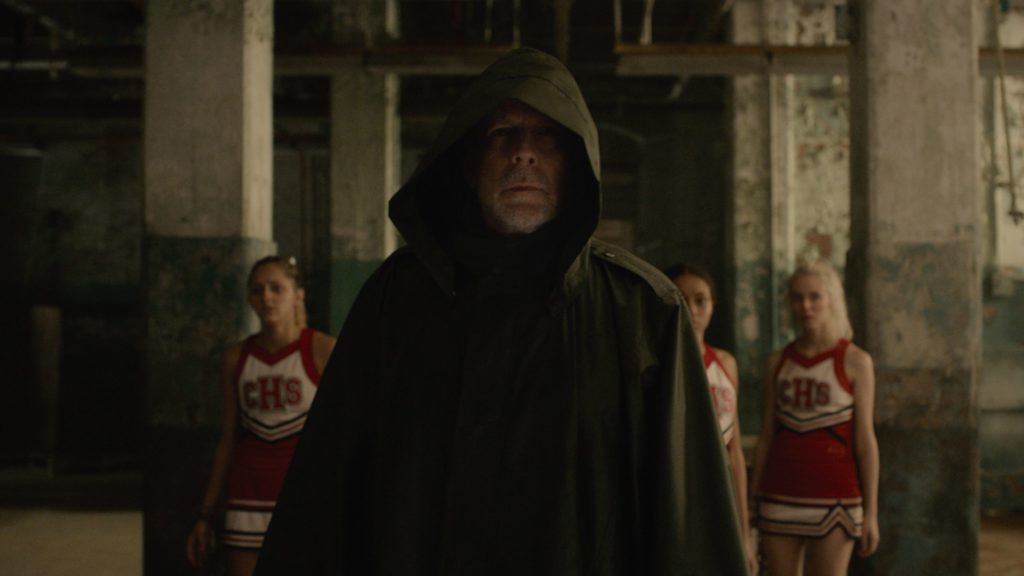

Ha! But even if Shyamalan’s films are more distinctive than those churned out by the superhero industrial complex of Marvel and DC, his conception of Dr. Staple remains a grave miscalculation, dulling Glass’s suspense and throttling its pacing. Having already seen Unbreakable and Split, we know with certainty that these characters are extraordinary, which means that Dr. Staple is either a complete moron or a gaslighting fraud; neither of these scenarios is very interesting, especially not during talky scenes when she tries to convince David that his tangible visions of the future can be attributed to his possessing the intuitive gifts of a magician, or to compare Kevin’s beastly wall-crawling to the feats of professional rock-climbers. (In this sense, Glass recalls the scene from The Terminator where cops and therapists try to convince Sarah Connor that she’s crazy, only it’s about four times as long.) Of course, it’s possible that Shyamalan is less interested in making us question his characters than in forcing them to question themselves—many of his movies, including Unbreakable and Signs, center on crises of faith—but even then, it’s difficult to find Dr. Staple’s probing compelling. After all, according to the timeline of this cinematic universe, David has been flexing his superhero muscles—typically in the guise of a hooded vigilante called The Overseer—for nearly two decades; he’s really going to start doubting his abilities because some shrink says he’s the bald David Copperfield?

So from a storytelling perspective, Glass fails to capitalize on its potential. But writing isn’t everything, and even when Shyamalan’s screenplay stumbles, his camera continually supplies tasty treats for the eyes and ears. The location helps: The asylum has a weird flavor all its own, most notably in a cavernous room with faded pink walls where Dr. Staple jointly interviews her three superhuman patients, each seated along the same horizontal plane, spaced apart with geometric precision. Their living quarters are similarly distinctive; David, whose kryptonite is water, is shunted to a large room that’s adorned with a spidery array of menacing pipes that promise to blast liquid at him if he makes a wrong move, while Kevin’s cell is outfitted with two massive banks of motion-activated strobe lights that flare to life whenever he gets too close, thereby forcing him to switch identities on command. (McAvoy obliges with evident glee.) These colorful decorative touches help lend even the banal interrogation scenes some visual kick.

Elijah’s room is more spartan, though here Shyamalan is playing the long game. The brittle-boned mastermind of Unbreakable spends the first half of Glass in an apparent stupor, strapped to a wheelchair and unresponsive to all external stimuli. It takes nearly an hour before he opens his mouth, but it’s worth the wait, with a killer jolt that gives literal, gory meaning to the film’s title. And once Elijah and The Beast decide to team up—a villainous collaboration that necessarily requires David to activate his rugged heroism—Glass starts to take off, operating as both a giddily escalating thriller and an actorly showcase. Jackson can still be a ferocious screen presence when he wants to be, and he invests Elijah with delectable superiority without ever leaving his chair. The physicality is left to McAvoy, who once again throws himself into his performance completely, giving each of Kevin’s identities not just different vocal tics and mannerisms but their own apparent bearing, as though his body somehow transmogrifies with each blinding flash of light. Compared to them, it’s hard not to feel sorry for Willis, who doesn’t get to have nearly as much fun, and who lacks the requisite screen time to accumulate the soulful melancholy that helped make Unbreakable so quietly devastating.

That movie—and diehards will recognize some of its deleted scenes here, now repurposed as flashbacks—explicitly wrestled with the role of comic books in American fiction. It’s a theme Shyamalan revisits here, and his palpable affection for the graphic novel can be both enlivening and enervating. Sometimes he channels his love of the form with playfulness and wit, as when a character finds himself in a novelty store staring up at a neon sign that reads “Villains”, or when Elijah casually imagines the splash panels that might pop above the head of a bewildered orderly shortly before his grisly death. On other occasions, particularly when it involves weaving comics directly into the film’s plot, Shyamalan’s mania scans as affectation, a fanboy’s insistence that his movies are made for the people, by the people.

But he is an entertainer, and even at its bluntest and broadest, Glass thrums with energy and propulsion. It isn’t really an action movie, but Shyamalan’s auteurist approach gives the handful of fight scenes a strange intimacy, the camera digging in close to absorb his combatants’ sweat and capture the weight of their grunting exertion. And while the climactic showdown between The Overseer and The Beast occasionally suffers from superhero smackdown syndrome—two titans can only pummel one another for so long before it becomes monotonous—there’s still a level of flair to the brouhaha that feels bracing. “You must think you’re in a toy store,” Elijah memorably said in Unbreakable; “this is an art gallery.” Glass may be little more than Shyamalan mashing his toys together in a giant sandbox, but he’s making art all the same.

So is McAvoy, who again proves that it’s possible for a professional actor in a genre picture to hone his craft and have a blast at the same time. Yet if his delirious performance is the heart of Glass, its soul belongs to Anya Taylor-Joy. She again plays Casey, one of The Beast’s terrified victims in Split who escaped his clutches through a combination of ingenuity and empathy. Casey is hardly essential to the story, but unlike the other returning secondary characters—Spencer Treat Clark again shows up as David’s now-grown son, while Charlayne Woodard is back as Elijah’s insistently supportive mother—her presence really means something. Her few conversations with Kevin are freighted with tenderness and loss, and in just a few short scenes, Taylor-Joy uncovers a whisper of genuine pathos that the rest of the film eagerly courts but struggles to secure. Perhaps that’s fitting for the disjointed Glass, an enjoyable mess of a movie that is deeply silly, sharply executed, and, in the briefest of moments, softly shattering.

Grade: B

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.