Early in Ad Astra, James Gray’s searching, often astonishing, deeply frustrating new film, a man finds himself sitting alone at a kitchen table. A woman, whom we presume to be his wife, enters the background of the frame and starts to walk into an adjoining room, then stops and tilts her head to look at her husband. At this point, most directors would pull focus from the man to the woman, allowing us to discern her expression, be it pensive, affectionate, or disapproving. Gray, however, keeps his camera trained on the man in the foreground, watching his impassive features as he remains still, refusing to turn and look at his spouse. The woman leaves the room as she arrived, a blurred outline: hazy, indefinite, unknowable.

In terms of plot, this is one of Ad Astra’s least essential scenes. But it’s still a revealing moment, demonstrating both its director’s purposeful technique and his thematic and visual priorities. The man at the table isn’t just the movie’s main character but our sole point of entry. He appears in every scene of the film and conveys its lofty ideas, whether through his wistful demeanor or via one of his numerous, egregiously unnecessary voiceovers; here, he informs us that he is focused on his mission to the exclusion of all else. Yet while Ad Astra aspires to be both a bold adventure and a poignant character study—a somber interstellar epic that explores the mysteries of the universe by way of one man’s scarred psyche—its more accurate embodiment is the blurred outline of that faceless woman. With his customary craft, Gray has made a sweeping study of humanity that, despite its strenuous efforts, never feels especially humane.

Then again, maybe Gray didn’t pull focus away from the man because he didn’t want to take his eyes off Brad Pitt. Who can blame him? Now 55 and still every inch a matinee idol, Pitt’s face is both chiseled and delicate, underlined by a square jaw and topped by casually perfect hair. His work here matches the overall texture of Ad Astra: gorgeous, sensitive, and not particularly resonant. To be fair, his character—a supremely competent astronaut named Roy McBride—is a challenging role, requiring him to internalize feelings of grief and loss mostly through his eyes, those baby-blue windows to the soul. The problem is that, for all his beauty and charm, Pitt has never been the most soulful actor. As Roy, he supplies the idea of a great performance—heavy sighs, thousand-yard stares, the occasional tear—without generating much depth.

And oh, how Ad Astra yearns to be deep. Gray’s screenplay, which he wrote with Ethan Gross, is strewn with moments of pseudo profundity, virtually all of which are clumsily delivered through Roy’s thudding, on-the-nose voiceover. Among other things, the film is a study of parental desertion and filial devotion. Roy’s father, Clifford (Tommy Lee Jones), was a legendary space-walker who disappeared years ago while executing the Lima Project, a mission designed to scour the solar system for signs of intelligent life. With Earth now being beset by a series of mysterious power surges, Roy’s superiors inform him not only that his father might still be alive, but that his spacecraft was carrying a deadly substance that could be causing the surges; they thus task him with contacting Clifford in the hope that he might be moved by a plea from his long-lost son.

It’s sort of 2001 crossed with Apocalypse Now, only if Colonel Kurtz had once been a proud papa. If you’re unsure about the hardships that Clifford’s absence has caused Roy, all you need to do is listen; there’s a sequence where Roy explicitly states that sons are prone to suffering for—and repeating—their fathers’ sins. It’s an oddly literal concession from Gray, a filmmaker who typically allows his movies to gather force through the grand scale of his narratives and the majesty of his images.

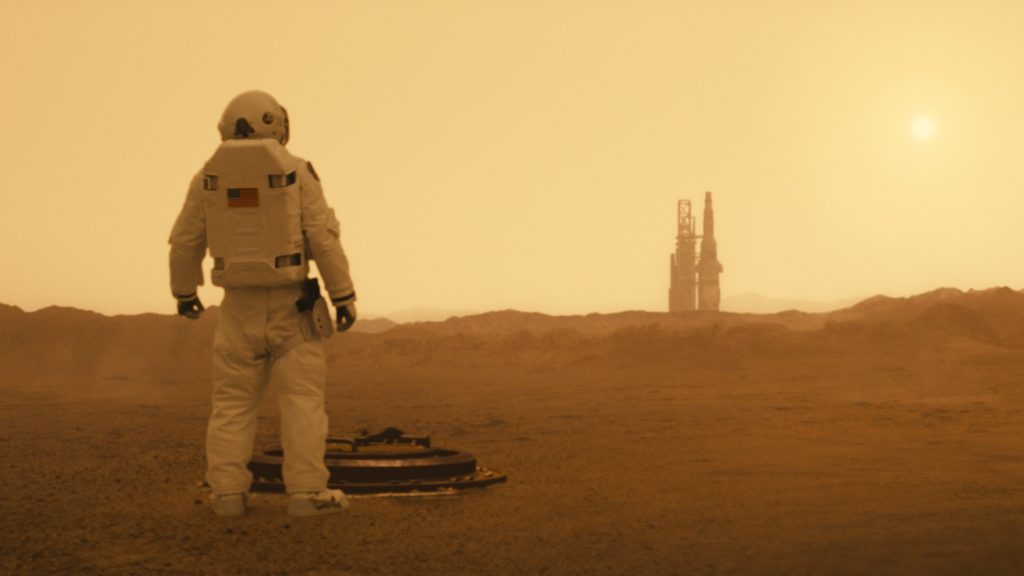

And Ad Astra certainly has plenty of those. Working with Hoyte Van Hoytema, the cinematographer who shot Interstellar (still, for this critic’s money, the best space-set movie of the new century), Gray skillfully communicates the sheer vastness of the cosmos—that familiar shot of Earth, glimpsed from beyond as a giant blue orb, has rarely been so striking—while also making room for smaller, more intimate sights and sounds. (The score, by the great Max Richter, is predictably lovely.) A handful of scenes set on Mars pulse with an amber glow, while sequences that take place in outer space possess their own peculiar but rigorous geography, vessels seamlessly interacting with one another as they float along in the void.

In a way, Ad Astra is a logical progression for Gray, whose prior film, The Lost City of Z, gracefully charted a colonist’s mounting interest in the ancient tribes of Amazonia, watching mournfully as his enthusiasm gave way to obsession. Now, Gray has turned from the past to the future—and from the jungle to the stars—while still exploring weighty themes of family, discovery (of the self and of the world), and masculinity. He’s a naturalistic director who is nevertheless well-suited for science-fiction, a genre that encourages artists to ask probing, metaphysical questions about the nature of existence; hell, the very concept of space travel invites rumination on the makeup of our species, as well as its uncertain prospects.

Yet for all its noble ambitions, Ad Astra never clicks emotionally because it fails to create interesting characters. All of the supporting players are one-note, including Liv Tyler as Roy’s (mostly silent) wife, Ruth Negga as a scientist with a vendetta, and Donald Sutherland as a wizened conspirator. (Natasha Lyonne shows up for a pointless cameo that nonetheless injects some random energy into the proceedings.) And despite abundant shots of Pitt looking sullen inside his pristine helmet, Roy himself is a distant presence whose superhuman abilities only make him more remote. He’s so good at his job—we learn that his heart rate has never exceeded 80 beats per minute, not even when he’s free-falling through the atmosphere—he makes Ryan Gosling’s Neil Armstrong look like a fourth grader. Curiously, he’s at his most vulnerable when he submits daily self-evaluations to a computer, describing his state of mind and testifying as to his mission readiness; these de facto therapy sessions are designed to provide insight into his personality, but they really just reinforce the character’s central blankness.

These failures are disappointing, but Ad Astra is still very much worth seeing, both for the splendor of its visuals and the vitality of its set pieces. The movie’s tone may be solemn and sedate, but it feels most alive when it’s in motion, with Gray delivering a handful of showstopping sequences. The opening is a stunner, following Roy as he clambers around on a space station and then suddenly tumbles downward into the atmosphere and toward the rapidly encroaching ground; as Roy calmly updates command on his predicament, Gray communicates the breathlessness of the fall with both intensity and clarity. Later, there’s a car chase on the moon—behold, space pirates!—which is both invigorating and oddly realistic, as is a claustrophobic knife fight that takes place in a ship’s cabin, the zero-gravity air soon flecked with suspended droplets of blood. And a wayward rescue mission takes a wonderfully terrible turn, momentarily rattling the film’s sterile interiors with animalistic savagery.

It’s hard to fault Gray for seeking to graft these robust scenes onto an operatic story of purported philosophical meaning: about man’s selfishness, his loneliness, his desperate need to come face-to-face with his creator. All the same, the film feels empty, its collage of prettiness never coalescing into the powerful statement it craves to make.

At one point, Roy recounts how his father was fortunate enough to witness sights that were “magnificent and beautiful” but that he never dug below their surface. It’s a stark assessment that feels like an acute diagnosis of Ad Astra itself. Gray wants to wield his considerable cinematic gifts to bring us closer to humanity, to ourselves. But as this admirable, elegant, ultimately unsuccessful movie plunges ever deeper into the unknown, it only moves increasingly further away.

Grade: B-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.