Of course Uncut Gems opens with an extreme close-up of a colonoscopy. After all, this nasty, edgy, oddly exhilarating movie is the work of Josh and Benny Safdie, those sibling purveyors of stomach-churning New York City sleaze. Their prior film, Good Time, steeped itself in grimy brutality, featuring all manner of crimes, deaths, and maulings. Their new picture, as its initial footage of a man’s digestive tract suggests, in no way eases up on the throttle; it’s another portrait of a desperate man, and it’s uncompromising in its vulgarity and intensity. Yet there’s something strange about Uncut Gems, something shiny buried within its crusty shell of unfiltered savagery and heedless aggression. It is—and I can’t believe I’m writing this, given that the Safdies’ filmmaking ethos seems to involve making the viewing experience as nauseating as possible—fun to watch.

Whether it’s pleasant to look at is another matter. With each new feature—before Good Time, they made the low-budget addiction drama Heaven Knows What, starring mostly non-professional actors—the Safdies grow increasingly accomplished in refining their distinctive style. It is not an aesthetic I particularly care for. The camera is wobbly, the music (again by Daniel Lopatin, aka Oneohtrix Point Never) is invasive, and the lighting is, well, not very light; many scenes play out in dim interiors, with unflattering illumination that makes the actors look wan. Occasionally, they subvert their grungy approach in productive ways, such as when a musician activates a black light at a nightclub, suddenly brightening the screen with bolts of neon. The veteran cinematographer, Darius Khondji, has worked with David Fincher, Bong Joon-ho, and Michael Haneke, and he helps modulate the Safdies’ signature freneticism with a measure of discipline. Still, for the most part, this movie looks gritty, sickly, and ugly.

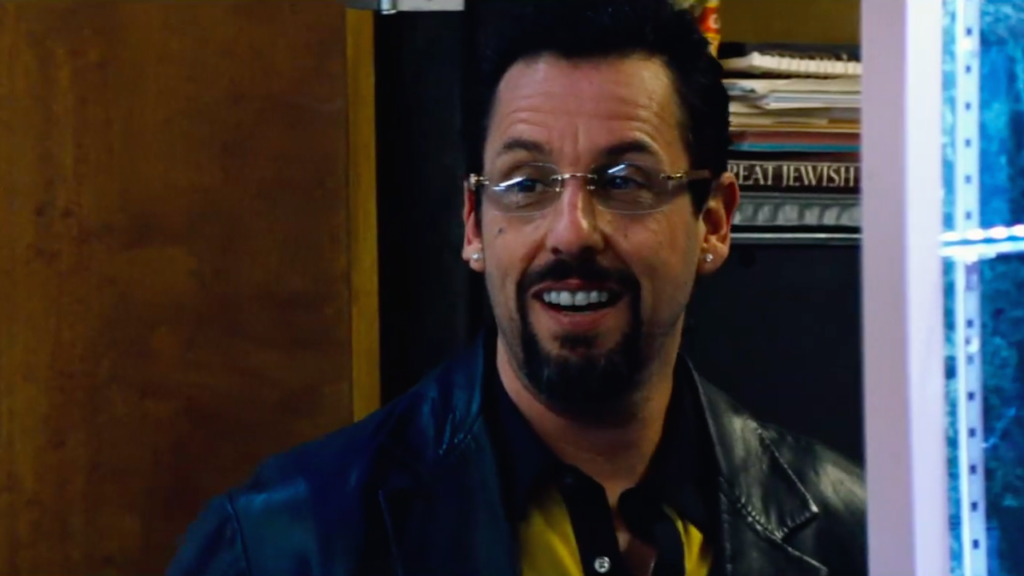

Again, this is hardly accidental, especially given the way it aligns with the film’s characters and themes. Running 135 bruising minutes, Uncut Gems is an unyielding odyssey of stupidity and panic. Most of the people we meet, if not outright evil, are either vain, selfish, or cruel. They engage in beatings, humilitations, double crosses, and profane insults. Tempers are always heating up as a clock keeps ticking down. But while the Safdies’ visuals are unappetizing, the atmosphere that they conjure—a miasma of incipient chaos and vertiginous anxiety —is weirdly engrossing. And the primary reason for their success—once again, I can’t believe I’m writing this—is Adam Sandler.

Actually, this one I sort of can believe. Amid his phoned-in comedies and glorified celebrity hangout productions, Sandler has periodically proved that he’s a talented actor, one who’s especially skilled at throwing himself into characters afflicted with a type of mania. (Punch-Drunk Love is the most obvious example of his gifts, though he was also quite good in Funny People, The Meyerowitz Stories, and even The Week Of.) That description surely applies to Howard Ratner, the Diamond District jeweler and gambling addict whose misadventures form the heart of Uncut Gems, and whom Sandler depicts with a singular combination of duplicity and sincerity.

Howard is, to be polite, a mess. When the film opens, he owes six figures to a loan shark named Arno (Eric Bogosian), who has dispatched a burly enforcer (Ketih Williams Richards, terrifying in his first ever role) to collect his debt. He is separated from his wife, Dinah (Idina Menzel, underserved), and possessive of his girlfriend, Julia (Julia Fox, making an impression). His teenage daughter can’t stand him, and his chief employee, Demany (Lakeith Stanfield), doesn’t respect him. His compulsion requires that, whenever he comes into money, he immediately places another bet. He is foolish, irresponsible, and untrustworthy.

And also kind of charming. As Sandler plays him, Howard is a gregarious presence: always in motion, always talking, always eager to yammer about diamonds or Passover or the Knicks. The Safdies hardly shy away from illustrating the predatory nature of the gambling trade—a vicious cycle of spiraling, where the only thing worse for an addict than losing a bet is winning one—but they also conceive of a vibrant and interconnected world, a fraternity whose members are united by shared knowledge and common interests. As Howard streams into pawnshops and restaurant kitchens, he takes evident joy in the camaraderie he feels with the bookies and brokers who are all too happy to take his money. Sandler imbues this hapless, cheerful jeweler with a certain buoyancy, a friendly agitation and quixotic enthusiasm that makes him both thoroughly pathetic and deeply likable.

It’s crucial that we sympathize with Howard, because the plot of Uncut Gems centers on him making one terrible decision after another. This cascade of self-inflicted misfortune begins after Howard acquires from Ethiopian miners a black opal, which he hopes to sell at auction for over a million dollars; overwhelmed by his excitement, he immediately parades the precious stone to everyone in his shop, catching the eye of Boston Celtics star Kevin Garnett (playing himself, and well). In the midst of a second-round playoff series (the movie is set in 2012), Garnett convinces Howard to let him hold the opal for an evening, offering up his 2008 NBA championship ring as collateral. (The Safdies are basketball junkies; six years ago, prior to making Heaven Knows What, they directed a documentary about failed phenom Lenny Cooke.)

What follows, much like in Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant, is an exponential daisy

chain of high-stakes maneuvers, as Howard continually takes greater risks and becomes

helplessly overleveraged; he hocks Garnett’s ring to a pawnbroker, who lends

Howard cash that quickly makes its way to a bookie, which inspires a visit from

an enraged Arno, and so on. The Safdies convert Howard’s recklessness into fuel

for an escalating nightmare, which also happens to be disturbingly plausible; it’s

easier to follow if you have a gambling problem yourself are fluent in

the language of sports betting, but you don’t need to understand terms like “parlay”

or “money line” to recognize the depths of Howard’s pathology. An early scene,

in which he repeatedly insists that customers not lean on the glass countertops

which shield his jewels, functions as a perfect metaphor; as the film progresses,

you keep waiting for that glass to break, and for its protagonist’s world to

shatter.

It’s queasy stuff that could have disintegrated into glumly assaultive schlock, but what rescues Uncut Gems—besides Sandler’s relentlessly watchable performance—is the relationship between Howard and Julia. The obvious differences between Sandler and Fox—in terms of both age (he’s 53, she’s 29) and attractiveness (she’s a former model, he’s… Adam Sandler)—suggest that their characters’ love affair will be transactional rather than romantic. The surprise of the Safdies’ screenplay, which they wrote with Ronald Bronstein, is that it considers this seemingly mismatched pairing with honesty and sentiment, resulting in a bond that is, if not entirely persuasive, legitimately tender. For the most part, the movie is a work of ruthless momentum and unstoppable force, but its sweetest scene has nothing to do with its narrative of catastrophe; instead, it finds Howard hiding in a closet, exchanging sexts with Julia as he secretly watches her undress. In a film that otherwise draws its power from unwavering harshness and distress, it’s an oasis—playful, happy, and hot.

And while its defining fervidness never slackens, in its final act Uncut Gems shifts from an unnerving movie to an entertaining one. Its climax features little more than Howard watching TV, but it’s nonetheless riveting thanks to Sandler, who brilliantly communicates the unparalleled euphoria of the bettor, the diseased man who lives and dies with every whistle, turnover, and foul shot. It’s a truly thrilling sequence, and it locates a sort of valor within its hero’s derangement. Howard may be a lunatic and an addict, but he sure as hell believes in something.

And so do the Safdies. Specifically, they’re adherents of the notion that cinema should be an energetic and immersive medium, and while I don’t fully admire their technique, I can’t quarrel with their commitment. Among the many dubious schemes that Howard contrives in the film is the peddling of a counterfeit Rolex. It’s yet another dangerous move with looming consequences, but it’s also something of a feint itself. Uncut Gems may be raw, but it is definitely not a fake.

Grade: B+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.