Jane Austen’s Emma is a comedy of manners, which of course means that nobody in it is actually polite. It may unfurl in high society—the kind where estates have proper names, like Donwell Abbey and Hartfield —but its veneer of decorum is a mere smokescreen, camouflaging base instincts of lust, greed, and jealousy. Its language is unfailingly civil, with a premium placed on honorifics—Mr. Elton! Miss Smith!—but its characters wield words like weapons, brandished with lethal force and sheathed with calculated fury. It’s a frolicsome tale of romance and friendship; it is also blood sport.

This duality can be bracing, but for most viewers it is no longer surprising, given how frequently Austen’s novels have been transmuted to the screen. Her works provide a certain comfort, a warm and familiar blend of sophisticated wordplay, comic misunderstandings, and graceful resolution. This new adaptation of Emma, which has been directed by Autumn de Wilde from a screenplay by Eleanor Catton, respects its author deeply and faithfully. Unlike Clueless, which boldly transplanted Austen’s narrative and themes to the frivolous exploits of mid-’90s teenagers, this Emma is frank and straightforward. You might think that such a rigorous approach would result in the diminution of risk, in an absence of artistic identity or imagination. To be sure, the movie is predictable. It is also magical.

The spell that it casts is easy enough to learn but difficult to master. De Wilde enters this battle armed with the bristling wit of Austen’s prose, but her unenviable challenge is to infuse the novel’s tart intelligence with cinematic vitality. She succeeds by mounting a production whose achievements are visual as much as verbal. Certainly, the dialogue sparkles with droll humor, featuring a dizzying array of one-liners that are simultaneously refined and savage. But de Wilde’s Emma is more notable for its skillful presentation—for the way it enlivens the novel with pictorial verve.

This is not just a matter of pretty pictures, even if the picture is very pretty. The production design is beatific, full of verdant grass and handsome homes and soft candlelight. The costumes—a veritable fleet of waistcoats, hats, and gowns—are resplendent. The music, by David Schweitzer and Isobel Waller-Bridge (yes, Phoebe’s sister), ripples with genteel energy. But de Wilde has done more than helm a nice-looking period piece. She has also created a complex choreography of visual emotion, a symphony whose instruments are glances, smiles, and scowls.

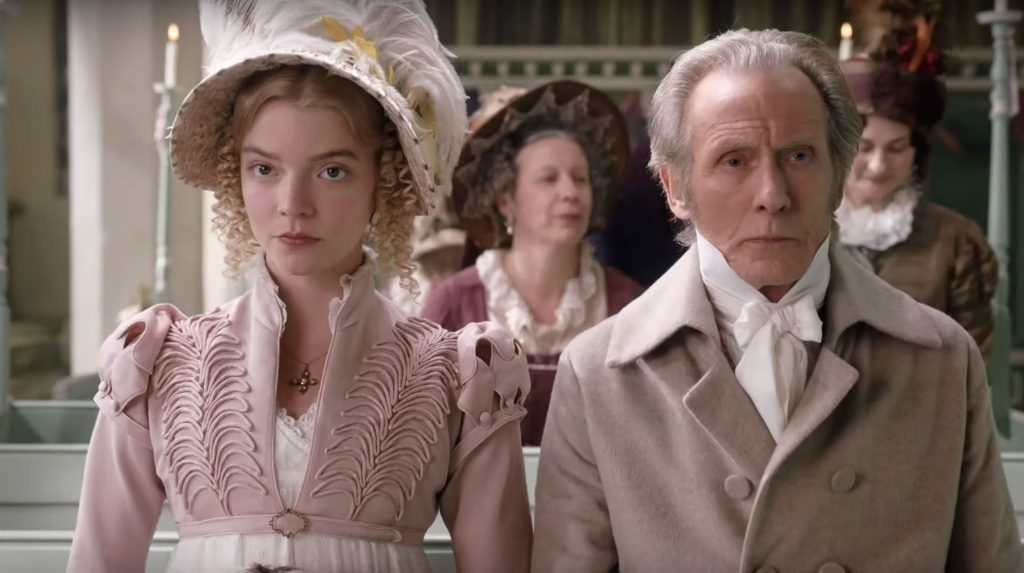

In Emma, where even the harshest insults are smuggled inside the most delicate phrases, facial gestures tend to speak louder than words. De Wilde, a photographer and music video director making her first feature, understands how sentiment can be conveyed through movement and body language. The film is full of moments of expressive silence; when two characters arrive for a sermon and discover that their customary pew is already occupied, their look of aggrievement is such that you might expect them to start a riot. De Wilde mines such sequences eagerly, illustrating how her players’ placid surfaces disguise the anger roiling underneath. In this, she relies heavily on her star, which is sensible, because the greatest thing about Emma is the woman playing Emma.

Over the past several years, Anya Taylor-Joy has quietly established herself as one of American cinema’s most gifted young actors. She specializes in playing reserved, watchful characters: a wary ingénue in The Witch, a terrified kidnapping victim in Split (and again in Glass), a maladjusted sociopath in Thoroughbreds. That’s what makes her performance here such a revelation. Emma Woodhouse is a lot of things—clever, vain, superior, conniving, sad—but she is in no way timid. And Taylor-Joy emphasizes her unwavering confidence even when she isn’t speaking in clipped, precise tones. When she glares at someone, her eyes dart with cruel purpose. When she turns her head—which is framed by a set of dainty blond ringlets that might as well be pieces of chain mail—she swivels it with ferocity. And when her lips curl upward into a smile, her face emanates with the heat of the sun.

No doubt Emma would pooh-pooh such praise as hyperbolic, even if she might secretly approve of it. As Austen heroines go, she’s a curious creature: smart, charming, and kind of awful. She’s delightful company, no question; her conversations with her father, Henry (a typically wonderful Bill Nighy), ooze with haughty intellect, while her rapier exchanges with her brother-in-law, Mr. Knightley (Johnny Flynn, soon to play David Bowie in Stardust), carry a charge that’s part poetry, part combat. But she is also a busybody and a snob, and her righteousness mingles dangerously with her taste for manipulation. The pleasure of Emma lies not in the havoc that its title character wreaks on others’ lives, but in her own gradual reconciliation between her innate stubbornness and her dawning self-awareness.

The catalyst for this process is the arrival of Harriet Smith (Mia Goth, from Suspiria and High Life), a young woman of unknown parentage; Emma instantly befriends Harriet and decides to mentor her, which means she inadvertently risks ruining the poor girl’s life. Harriet is smitten with Mr. Martin (Sex Education’s Connor Swindells), but Emma determines that this meager farmer is beneath her new companion and instead resolves to pair her with Mr. Elton (The Crown’s Josh O’Connor), the simpering local vicar. He’s more interested in Emma herself, who in turn has her eye on Frank Churchill (Callum Turner), a wealthy fop who seems to share her liking for trivial amusements. Emma also finds herself ensnared in a rivalry of one-upmanship with Jane Fairfax (Amber Anderson), a highly accomplished governess whose cordiality might be masking something more sinister. (Later, a woman with ridiculous hair shows up to further complicate matters; she’s played by a fabulous Tanya Reynolds, also from Sex Education.) All the while, Mr. Knightley looms with apparent dispassion, his arch wisdom occasionally giving way to flashes of genuine emotion.

You know how all of this plays out, even if you haven’t read Austen’s book or seen one of its many prior screen adaptations. There will be devious double-dealings, ghastly misapprehensions, and painful realizations. Villains will reveal their true natures, while meek characters will discover their inner strength. Hearts will temporarily break, but in the end, true love will prevail.

Again: None of this is surprising. Austen was a born crowd-pleaser, and in translating her novel with such care and conviction, de Wilde appears to share her thematic preferences, favoring fidelity and buoyancy over transgression and rebellion. As recent period pieces go, Emma is not as aesthetically luminous as Joe Wright’s Pride & Prejudice, nor is it as structurally daring as Greta Gerwig’s Little Women. And in hewing to her source material so closely, de Wilde inevitably retains some of its limitations, in particular its archaic equation of matrimony and happiness.

Yet much like Emma’s own failings are mere stumbling blocks on her way to salvation, these flaws seem insignificant in the face of a movie so full of joy. It’s there in the big dance sequence, one of those numbers where everyone knows all of the fancy steps, and where the slightest touch brims with unspoken longing. It’s there in Nighy’s marvelous exaggerations—his character’s sheer terror at the prospect of “Snow!? Tonight?!” is alone worth the price of admission—and in the way he pointedly orders servants to place windscreens all over his drafty house. It’s there in Taylor-Joy’s face when Emma delivers a respectable rendition on the piano, then smugly turns things over to Jane (“Such a shame you didn’t bring your music!”), only to be flabbergasted by the latter’s powerhouse performance. And it’s there even in moments of confusion and shame; a sudden nosebleed will make you gasp, as will the scene where Emma blithely insults a poor, kindhearted woman (a very fine Miranda Hart), her cutting remark cracking out louder than any gunshot.

Speaking of shame, I’ve thus far elided the period that appears in Emma’s official title, which I deemed a pointless punctuative flourish. It probably still is. But perhaps it’s designed to underscore the declarative nature of its protagonist—how she acts with such self-assurance, and how she refuses to suffer fools, even though she is one herself. In that spirit of bluntness, allow me to sum up. Emma may indeed be awful. But Emma is sublime.

Grade: A-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.