The COVID-19 pandemic has ruined lives, crippled economies, and paralyzed entire nations, but what has it meant for the movies? The received wisdom is that 2020 has been a lost year for cinema, and there’s a degree of truth to that; I’ve lost count of how many major studio releases have been delayed until 2021 or beyond, and many other films—which ordinarily would have had the opportunity to chase eyeballs on the big screen—were unceremoniously interred in the graveyard that is VOD. But while it’s understandable to lament the movies that this year has taken from us, it’s also important to acknowledge those that it’s given us. The dearth of blockbusters created a cinematic vacuum that was promptly and happily filled by scrappier, less conventional titles: quirky comedies, chilling horror flicks, tender romances, robust actioners. And many of these movies came from a demographic that Hollywood has long neglected: They were directed by women.

Perhaps this has nothing to do with COVID-19; maybe 2020 was already shaping up to be the Year of the Woman even before the coronavirus reached American shores. Regardless of causality, it’s oddly invigorating to survey the year’s best films and to see how many were helmed by women, and with such variety. Consider: the quiet agony of The Assistant and the boisterous fun of Birds of Prey. The contemporary sadness of Cuties and the classical enchantment of Emma. The male friendship of First Cow and the female solidarity of Never Rarely Sometimes Always. (I dissented on both The Old Guard and Shirley, but other critics would surely point to them as well.) Women have always been making good movies, but their collective voice seems to be growing louder now, telling stories of ever-greater urgency and vitality.

Last month saw the arrival of two more female-directed streaming releases: Julie Taymor’s The Glorias, a biopic of Gloria Steinem for Amazon, and Rachel Lee Goldenberg’s Unpregnant, a road-trip comedy for HBO. Both movies grapple directly with women’s rights, though in dramatically different ways; The Glorias, which runs nearly two-and-a-half hours, is designed to be a sweeping epic that spans decades, while the 104-minute Unpregnant is a defiantly small-scale venture that takes place over a few days. Not surprisingly, the shorter, spikier film is comfortably the better one.

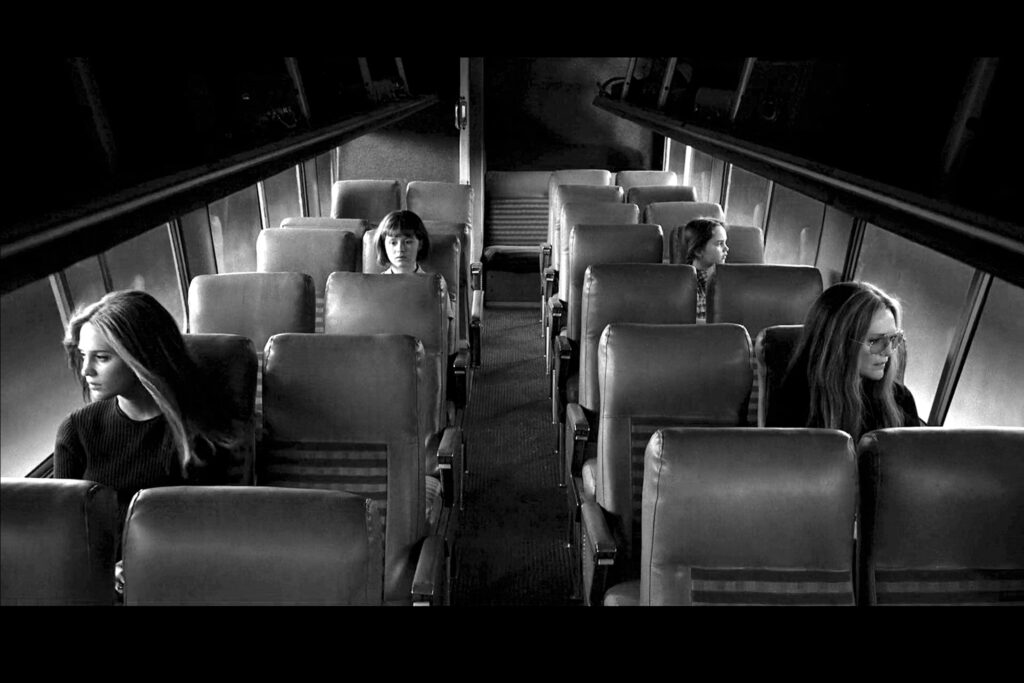

But while The Glorias isn’t a particularly good movie, it isn’t a boring one either. Taymor, perhaps suspecting that a linear recreation of her subject’s ascent would be dismissed as prestige “Oscar bait”, has taken great pains to infuse her production with cinematic energy and visual flair. Her most visible conceit is the creation of a metaphorical black-and-white tour bus, in which she strews together the four actors playing Steinem—they are, in ascending order of age, Ryan Kiera Armstrong, Lulu Wilson, a good-enough Alicia Vikander, and the always-good Julianne Moore—and allows them to interact with one another, relitigating past decisions and mulling future prospects. The editing is very busy, especially during the film’s first half, when it repeatedly loops back on itself, often returning to that bus which continually transports the Glorias (hey, that’s the title!) toward their symbolic destination. Later, there’s a surrealistic scene in which a misogynistic interview inexplicably transforms into a montage to The Wizard of Oz.

All of this is abstractly interesting; very little of it actually works. I commend Taymor for resisting the temptation to tell yet another straightforward story about an Important Person, but her repeated flourishes feel like random embellishments, rather than the product of a coherent filmmaking strategy or theme. Ironically, Taymor’s restless style only serves to underline the prosaic nature of her material; the bravado functions as a showy illusion, desperate to distract you from the picture’s narrative banality.

That said, as a piece of pop-culture hagiography, The Glorias isn’t without merit. The screenplay, by Taymor and Sarah Ruhl (based on Steinem’s book, My Life on the Road), does an estimable job compressing the key events in its protagonist’s life—her struggles breaking into the boys’ club of elite journalism, her creation of Ms. Magazine, her steady rise from “sex object” to equal-rights icon—with care and lucidity. The actors are steady, especially Moore, who never oversells Steinem’s larger-than-life stature and somehow makes her even more mythic as a result. (Timothy Hutton performs nicely as Steinem’s itinerant father, an unusual breed of movie parent whose flighty personality doesn’t take on undue meaning in his daughter’s development.) And the film’s message, about the complex intersection of social empowerment and personal sacrifice, carries undeniable force.

But its power is nonetheless diluted, not just by Taymor’s chaotic approach but also by her overly expansive scope. Gloria Steinem is an American hero, but The Glorias paints with such a broad brush, it never satisfactorily articulates her peculiar genius. She becomes just another organizer, a trailblazer, a Woman with Hopes and Dreams. We’ve met people like her at the movies before, and her on-screen familiarity diminishes her real-world significance.

Unpregnant supplies a more potent vision of feminine solidarity, if in a nominally less ambitious package. Directed by Goldenberg from a novel by Jenni Hendriks and Ted Caplan, its plot is decidedly simple: Veronica (Haley Lu Richardson) is a popular 17-year-old who gets pregnant. Scared of becoming a pariah, but unable to obtain a legal abortion in her native Missouri without parental consent—something she’s unlikely to receive from her devout family—she pleads with a long-estranged friend, Bailey (Euphoria’s Barbie Ferreira), to give her a ride to a clinic in Albuquerque.

What follows traces the typical trajectory of the road movie. Veronica and Bailey embark on an episodic adventure: meeting colorful characters, exploring new places, and falling into (and climbing out of) various predicaments, all while learning a bit more about each other along the way. As with most such films, some of the incidents work better than others; it’s always delightful when Giancarlo Esposito shows up (here as a paranoid survivalist with a heart of butter), but I could’ve done without the girls’ exaggerated run-in with right-wing activists, one of the rare times when this deceptively nuanced movie slips into caricature.

But the rich core of Unpregnant is the complex relationship between Veronica and Bailey. Goldenberg, a television veteran making her second feature (following the Valley Girl remake earlier this year), may not possess Taymor’s visual verve, but she exhibits a keen understanding of teenage friendships, depicted here as a syncopated medley of jealousy, dependency, rage, and love. Her actors are both on point; Richardson, so wonderful in both Columbus and Support the Girls (not to mention Split), resists broad gestures in favor of a gentler sincerity, while Ferreira is the ideal counterpuncher, hiding her scars beneath a mask of reflexive sarcasm.

Oddly enough, Unpregnant plays a bit like a distaff spin on Pixar’s Onward, another tale of two not-quite-simpatico teens racing against the clock in pursuit of an elusive goal. Yet its more obvious analogue is Never Rarely Sometimes Always, Eliza Hittman’s searing study of two young women battling an array of obstacles—financial, governmental, patriarchal—in their effort to gain access to healthcare. Unpregnant is a far sunnier picture, both figuratively and literally; there’s a quiet clarity to the way Goldenberg emphasizes the vivid spaciousness of the Southwest, illustrating just how long Veronica and Bailey’s journey is. But despite its comic overtones, it shares with Never Rarely a palpable fury—a sense of disgust that its heroine must take such drastic measures in order to vindicate her own bodily autonomy.

About which: The same day that I saw Unpregnant, Donald Trump announced his Supreme Court nomination of Amy Coney Barrett, intended to replace the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg. That bit of anti-serendipity lent my experience of watching the movie a greater charge; as this particular cinematic subgenre emerges, it’s hard not to wonder what it might look like a decade or two from now, and whether it will feel even more dystopian.

But Unpregnant isn’t successful purely on the basis of its message. It’s too vibrant for that, effortlessly accumulating the fine-grained texture that The Glorias badly lacks. It’s present in the way Veronica’s boyfriend (Alex MacNicoll) imagines himself to be a gallant hero when he’s really a possessive jerk, and in how her mother (Mary McCormack) wrestles with the conflict between her personal beliefs and her maternal love. One of the film’s sharpest touches lies in the seated dance duet that Veronica and Bailey ritualistically perform whenever they cross state lines. It’s a blissfully silly moment, but it also evokes true intimacy, silently communicating the depth of the girls’ shared history. The Glorias may chronicle the birth of second-wave feminism, but in lovely little moments like that, it’s Unpregnant that beautifully shatters the feminine mystique.

The Glorias grade: C+

Unpregnant grade: B

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.