Movies lie. They lie not as a callous display of dishonesty, but as a matter of literal operation; deception is a necessary function of the medium. Actors pretend to play other people. Directors manipulate their environments. Set dressers and production designers falsify the scene just so. Special effects wizards show us things that don’t really exist. Every movie is a lie, even if the best ones search for the truth. It’s an art form based on artifice.

The Father, which is currently contending for six Oscars (including Best Picture), explores this inherent contradiction to peculiar and unnerving effect. It features an unreliable narrator, but instead of mining that trope for suspense, it wields it for the purpose of immersion. That’s because The Father, which was directed by Florian Zeller from a screenplay he wrote with Christopher Hampton (based on Zeller’s play), actively grapples with dementia in a way that’s especially unsettling. It uses familiar cinematic tricks, often better associated with genres like horror or thriller, to bring you inside the diseased mind of its protagonist. It lies to you because lies are all its hero knows.

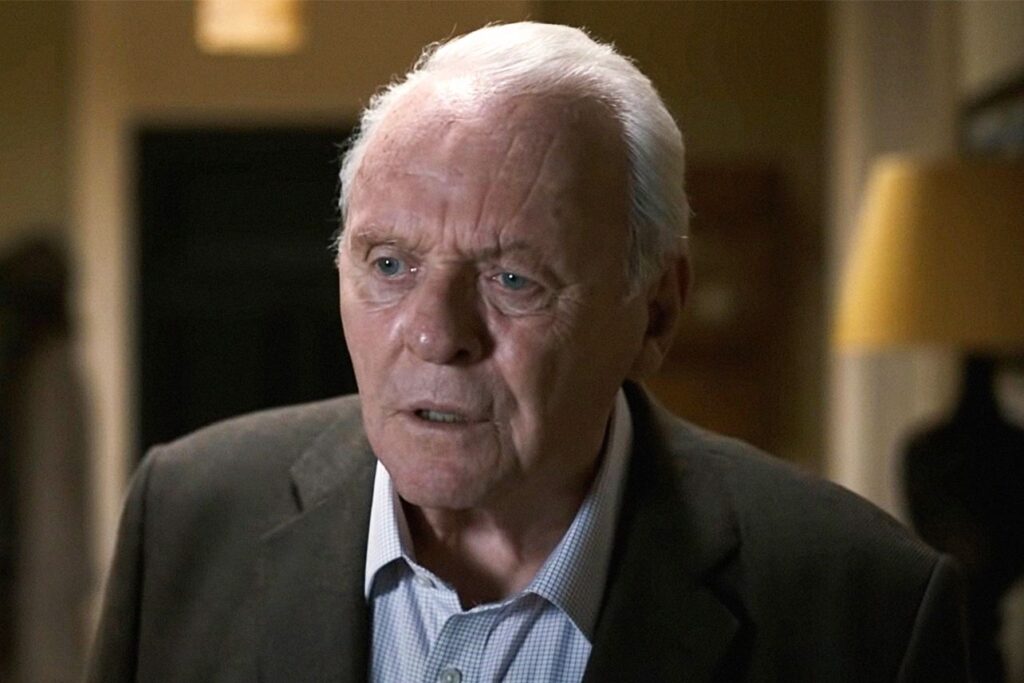

That hero is Anthony (Anthony Hopkins, giving his best performance in decades), a proud old man who lives alone in a smartly appointed flat in London. Or maybe he lives with his daughter, Anne, in her apartment. She’s played by Olivia Colman, except when she’s played by Olivia Williams. Regardless, Anne is divorced, or wait, is she still married? Her apparent husband, whose name is definitely either Paul or James, appears periodically, and in the guise of either Mark Gatiss or Rufus Sewell. Anne is Anthony’s only living child, or does he have another one? The caretaker whom Anne hires for the belligerent Anthony looks a lot like his younger daughter, Lucy, at least when she’s portrayed by Imogen Poots; at other times, she is instead played by… Olivia Williams.

Are you confused? Anthony sure is. And that, of course, is the point. The terrible genius of The Father is the way it loads up on these baffling incongruities with what might be called haphazard rigor. It calmly and cleanly presents a series of scenes that make no real sense next to one another, yet which all contribute to its ruthless depiction of mental decay.

This is a challenging exercise, fraught with danger. When we watch movies, we willingly accept the falseness of their construction, convincing ourselves that what we see on screen is real. (To quote Michael Caine in The Prestige: We want to be fooled.) But what happens when we can’t believe our eyes? The more directors toy with their audience, the greater risk they face of shattering the illusion—of inadvertently emphasizing the boundary between the watcher and the watched. The line between fascination and frustration can be thin.

And when I first saw The Father, I found myself rebelling against its careful organization, even as I admired its discipline and craft. Despite the film’s sober themes and sedate setting, Zeller’s shooting style isn’t that far removed from a horror picture, given how he builds tension and unease. One of his pet techniques—announcing another character’s arrival through sound while keeping the frame tight on Hopkins, then slowly revealing the new actor’s presence, like the unveiling of a ghastly surprise—is almost cruel in how effectively it develops suspense. In the moment, this method struck me as cold, even gimmicky. Should a man’s intellectual deterioration really be reduced to a succession of feints and shocks?

Yet having since wrestled with the film, I’ve warmed to its cool approach. The chief goal of The Father is to thrust you inside Anthony’s jumbled headspace—to make you struggle with a world where things are constantly off or out of place. Dementia has besieged his brain so thoroughly, it attacks everything, large and small, whether it means he’s failing to recognize members of his own family or repeatedly misplacing his wristwatch. In essence, Anthony is imprisoned in his own minimalist horror movie; his very life is a perpetual state of fear and mistrust, of being unable to understand what he sees—what we see—on screen.

And viewed through this lens, the film’s ostensible chaos—a parade of fakeouts, false starts, twisted repetitions (chicken for dinner, again?), and scattered callbacks (“They don’t even speak English there”)—becomes honest rather than manipulative. There’s an integrity to the presentation, both structurally and emotionally, because it functions as a clear-eyed look into a man’s increasingly blurry observations; the starkness underlines the empathy. And while it’s tempting to scour different scenes to determine what’s “real” versus what’s imagined, Zeller wisely avoids any moments of clarity, because to Anthony, everything is real.

The casting of Hopkins proves crucial here, and not just because the knighted Briton commits himself fully to the material. Hopkins is a naturally commanding presence, and his foremost quality is his withering intelligence; whether he’s a serial killer or an abolitionist lawyer or a robot-park designer, he is always the smartest guy in the room. The Father brilliantly leverages our inherent acceptance of his cerebral supremacy, which makes the faltering of his certitude all the more devastating. There is something profoundly disturbing about the sight of Hannibal Lecter crying for his mommy.

That late scene is the only moment where Zeller allows Anthony (and Sir Anthony) to break down. Otherwise, there is no catharsis to be found—only gnawing, quivering dread. It’s classic horror, only the demon here is disease. I headlined this piece with a question, wondering if The Father plays fair with dementia, but the answer might be irrelevant. What really matters—and what this movie illustrates with agonizing lucidity—is that dementia doesn’t play fair with the father.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.