The traffic light works. That’s how we know, even before the appearance of a freighted title card (“Day 1”), that the opening scene takes place during the era has become colloquially known, during our collective struggle with COVID-19, as the Before Times. (Remember, even movies that were made before the pandemic are totally still about the pandemic.) So even though the small town’s main square seems oddly deserted, the signal’s automatic flickering from green to yellow to red instantly communicates an attitude of relative safety. Yet at the same time, the introduction’s formal composition—the smoothness of the camera, the emptiness of the streets, the chaotic footage glimpsed on a news broadcast—articulates an undeniable sense of Damoclean danger. The apocalypse may not have arrived yet, but it’s surely on the way.

This expertly staged opening sequence, which builds from needling anxiety to clammy tension before erupting into all-out mayhem, confirms John Krasinski’s considerable skill as a director. He’s only made a handful of features, but here he again evinces a talent for conveying information and atmosphere through canny visual details. When he supplies a simple shot of a timid boy wincing in panic as a fastball buzzes past him during a Little League game, he isn’t watching a sport; he’s defining a character.

A Quiet Place Part II, the follow-up to the surprise smash hit from 2018, presents Krasinski with a challenge that’s both familiar and peculiar. The Law of the Sequel demands that he expand the template of the original and refit its elements to a larger scale: bigger scares, higher stakes, more elaborate set pieces, the works. Yet what made the original A Quiet Place so wonderful was its smallness. It reimagined the post-apocalyptic thriller as a taut domestic melodrama, with only four characters, a handful of smartly designed locations, and an inimitably lethal threat. For the next chapter, Krasinski must recharge the proceedings with newfound complexity without sacrificing any of its marvelous simplicity.

He mostly pulls it off. Inevitably, Part II isn’t quite as ruthlessly tense as its forebear, and the delightful ingenuity of its premise—make a sound, end up in the ground—has lost some of its novelty. There is now far more dialogue, which dilutes the film’s uniqueness and blunts its visual flair. There are also quite a few new characters, a necessary evil that nonetheless diminishes the familial tenderness of the first installment.

What remains, happily, is the sure sense of rhythm. The Quiet Place movies are tales of survival, which means they alternate between slam-bang sequences of abject terror and more brooding scenes designed to both enrich the characters and amplify the pervasive sense of dread. Krasinski again balances these ingredients perfectly in Part II, and his set pieces are still tack-sharp; not long after that explosive prologue, he delivers another corker, switching between the perspective of his fleeing principals—fighting not just those malevolent creatures who hunt via sound, but also more mundane threats like a trip wire and a bear trap, the latter of which activates with a sickening crunch—and the ominous sight of a sniper rifle.

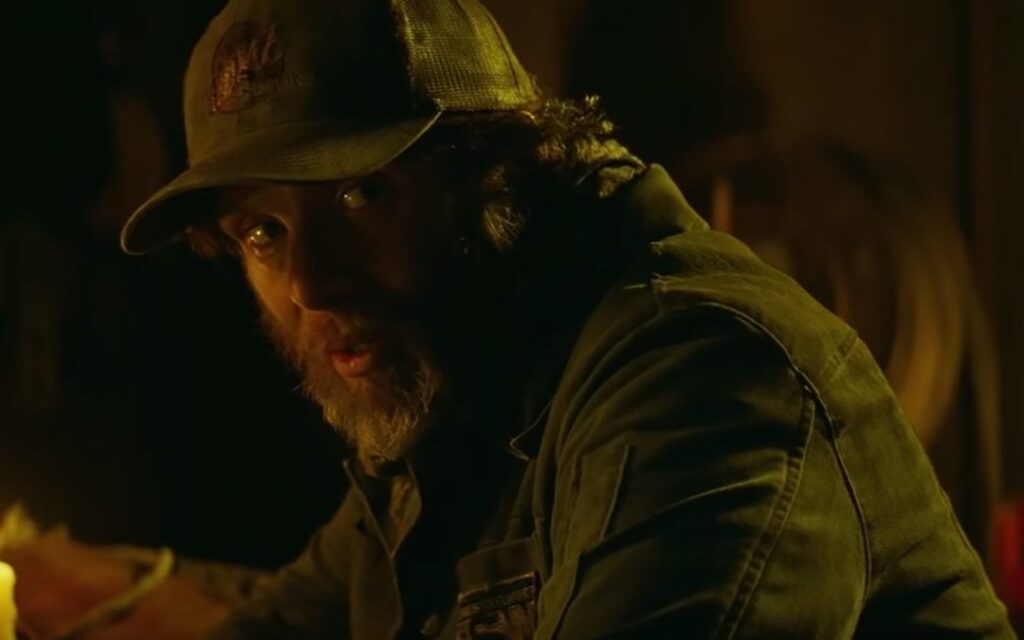

Speaking of those principals—they’re again the Abbotts, comprising Evelyn (Emily Blunt), Regan (Millicent Simmonds), and Marcus (Noah Jupe)—the most notable change in Part II is that Krasinski’s Lee is no longer among them, a consequence of (spoiler alert!) the sacrifice he made near the end of the first film. He’s been replaced, after a fashion, by Emmett (Cillian Murphy), a former family friend who’s grown more feral and less trustworthy. I don’t mean to minimize the Abbotts’ pain over their patriarch’s death, but purely in terms of casting, this is a sizable upgrade. If the original Quiet Place had a flaw, it was that Krasinski’s inherent sweetness nullified the ostensible discord between Lee and Regan. Murphy, sporting a grimy grey beard beneath those baby blues, is a shiftier and more enigmatic presence, and the tension that simmers between Emmett and the Abbotts—who early on crash his adopted pad at an abandoned foundry—feels genuine. You can’t risk taking your eyes off Emmett; you also don’t want to.

Structurally, where A Quiet Place functioned as a pure survival story, Part II operates as more of a quest narrative. Regan, upon hearing a certain Bobby Darin song on the radio, hatches a plan to mass-produce the makeshift weaponry—an ear-splitting procedure which combines a hearing aid, an amplifier, and a shotgun—that she and Evelyn previously stumbled onto, in the hope of eradicating the aliens. (Perhaps because the sequel takes place immediately after the original, the creatures are the one component that hasn’t been artificially upsized; they remain a deadly hybrid of Alien’s xenomorphs and the blind, sonar-wielding monsters from The Descent.) This requires her to leave the shelter of her family—an early scene, in which the Abbotts finally venture beyond the carefully soiled ground of their prior bungalow and begin treading on foreign land, nicely symbolizes their journey into the unknown—and travel to a possibly mythical haven. Splitting up his characters allows Krasinski to engage in some devious cross-cutting; a mid-film sequence in which he toggles between three very different predicaments, all equally perilous, is suffocating in its triple-pronged suspense.

There still isn’t a ton of weight to the picture, which mostly works in its favor; loading up on forced allegory would just bog down the pitiless intensity. That said, it’s worth grappling with the movie’s themes. In some ways, Part II is a far bleaker outing than its predecessor, at one point introducing a cabal of backsliding, tooth-and-claw predators whose primeval nature would fit snugly within the works of Cormac McCarthy. (The character actor who leads this chilling band of subhumans will delight cinephiles of a certain disposition.) Yet despite his merciless execution, Krasinski remains a rank sentimentalist. Ultimately, A Quiet Place Part II is a paean to some of humanity’s finest qualities: our resourcefulness, our perseverance, our enduring sense of hope.

Is that all bunk? Maybe, but whether it registers dramatically is unimportant. What matters here is the momentum, the desperation, the ubiquitous menace. Krasinski sprinkles the film with apocalyptic iconography—cars littering a bridge at haphazard angles, the wreckage of a train, the occasional desiccated corpse—that only deepen this world’s hellish descent into horror and madness. He also coaxes quality performances across the board. Blunt, who by critical law I must remind you is the director’s wife, is reliably persuasive, even if she has less to do this time around, while Jupe, despite looking markedly older than the timeline warrants, proves a capable shrieker. But Simmonds is the key. She has a preternatural talent for expressing her emotions through facial and body language, which makes her the perfect standard-bearer for a franchise in which speech is verboten. Together, she and Murphy create a marvelously dyspeptic partnership; a scene in which Regan quietly instructs Emmett to “ee-nuhn-see-ate” is startling in its whispered intimacy.

And A Quiet Place Part II is somehow both eerily hushed and fantastically loud. Again borrowing liberally from Steven Spielberg (to be fair, this time he lifts a different touchstone from Jurassic Park), Krasinski’s set pieces are inventive and invigorating, with enough wit and variety to stave off any sense of repetition. Periodically, he transitions to the deaf Regan’s point of view, and this change in perspective—invariably accompanied by a creature’s emergence in the background, something we can see but she can’t hear—is always gripping. He also uses patience to transform simple objects—a sprinkler, a cell phone, a dirty towel precariously placed on a vault door—into life-or-death totems. And of course, he pays off seemingly insignificant early moments (such as Emmett learning the sign for a particular baseball maneuver), contributing to the film’s overall economy and precision.

“How does it work?” Emmett asks Evelyn early, inquiring about the mechanics of her ad-hoc, alien-slaying workaround. “I don’t know,” she responds, “it just works.” It’s an honest answer, but there’s no real mystery behind the success of the Quiet Place movies. They’re classic examples of a director applying his craft, and of skilled actors imbuing a production with dimension and sincerity. Part II isn’t anything special, except that it’s pure filmmaking—the kind of painstakingly calibrated technique that compels you to lean forward in your seat, widen your eyes, and strain your ears amid the sound of silence.

Grade: B+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.