Some original screenplays are more original than others. Last week, for example, I reviewed Disney’s Free Guy, a jumbled, weirdly fascinating action comedy that prides itself on not being based on any existing intellectual property, then spins an entire film from references to (and rip-offs of) other intellectual properties. I was happy to see Free Guy perform well (it’s now spawning a sequel, naturally), if only because I want studios to keep making original movies. As if by magic, this past weekend featured the release of three such pictures, a veritable bonanza of novel #content. (Technically there were four, but I failed to make time for Martin Campbell’s The Protégé.) None is a perfect film—in fact, all three have considerable problems—but my disappointment is tempered by my enthusiasm for their very existence. I didn’t love any of these movies, but I did love that I was able to watch them.

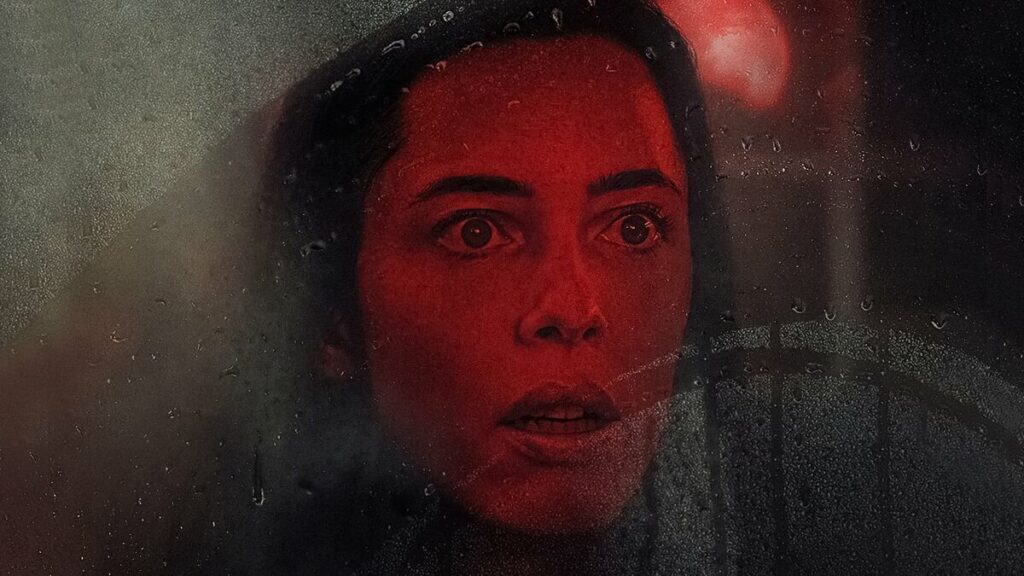

Of the trio, The Night House is the most conventional, which isn’t to say it’s typical. Directed by David Bruckner from a script by Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski, it’s a ruminative ghost story that’s less interested in freaking you out than pulling you in. Its heroine, a high school English teacher named Beth (a fantastic Rebecca Hall), isn’t just the frightened resident of a haunted house; she’s also a little bit scary herself. An early scene, in which she calmly shames a grade-grubbing parent into stunned silence, reveals her capacity for blunt anger, while a night out with colleagues quickly turns into an unhappy hour where busybodies tiptoe around a powder keg.

Beth has good reason to be mad. Her seemingly happy marriage to Owen (Evan Jonigkeit) has just ended after he rowed out to the middle of the lake that bounds their handsome Upstate New York home and shot himself in the head. Struggling to comprehend her husband’s actions, Beth is troubled by strange dreams and unexplained phenomena—bloody footprints, swinging doors, oddly behaved electronics. Is her grief just playing tricks on her? Or is there actually a shadowy presence lurking in her house, longing to pull her down to a darker realm?

As a horror movie, The Night House is uneven. It features some striking images, especially when it leverages its preoccupation with mirrors, as when Beth stares into the night sky and discovers two moons, a menacing red one opposite the ghostly white one. And it mostly plays fair, building suspense through an atmosphere of steadily encroaching dread rather than cheap jump scares; the handful of jolts it does provide tend to be diegetic—a knock at the door, a suddenly activated radio—rather than shakes of the camera or screeches in the score. Even the numerous dream sequences, so often a crutch for the genre, make sense here given that Beth finds herself sleepwalking, her subconscious constantly seeking out an explanation for Owen’s inexplicable death.

At the same time, The Night House’s mythology can feel blurry, both visually and thematically. Bruckner keeps the lighting dark, which is meant to make things spooky but which deadens some of the impact; there’s a difference between being terrified of the unknown and literally squinting at a hazy frame. (Some fault may lie with my local multiplex, which bafflingly refused to turn off the side lights.) And while the film wrestles with concepts of bereavement and depression, it struggles to articulate a coherent statement. This murkiness may be intentional—it would be lazy and crude to reduce Beth’s plight to a straightforward platitude—but the imprecision is nonetheless frustrating, as though a more powerful and provocative movie is just out of reach.

Where The Night House succeeds, and smashingly so, is as a star vehicle for Hall. An actor who improves everything she’s in yet remains perennially underappreciated, she captures Beth’s mounting fear without sanding down her more prickly qualities, like the glint of superiority that flashes beneath her interactions with a sympathetic friend (Sarah Goldberg, very good) and a potential romantic rival (Nymphomaniac’s Stacy Martin). The movie’s third act is its richest, and not just because of a faintly beautiful ending that splits the difference between tidy resolution and haunting ambiguity. It also features a showcase sequence where Hall strips away all of the character’s logical doubts and succumbs to the otherworldly. Even with its chilling kicker, it’s an enchanting moment, one that temporarily resolves The Night House’s central mystery. Hall isn’t playing off of anything but herself, but that’s plenty; the most potent presence on screen is the force of her own talent.

If The Night House puts a melancholic spin on one genre, Reminiscence tackles multiple familiar prototypes and attempts to meld them into something new. The feature debut of writer-director Lisa Joy (best known as the co-creator of Westworld), it grafts the darkly glittering futurism of sci-fi epics like Blade Runner onto the skin of a hard-boiled noir ripped straight from the pages of Raymond Chandler. There are newfangled technologies and half-drowned cities and a helplessly addictive drug called “baca”; there is also a world-weary specialist with a haunted past, a femme fatale with a secret agenda, and a conspiracy plot involving domineering men covering up their misdeeds. In a different universe, the movie might be titled, “Do Androids Dream of The Big Sleep?” (Bonus tagline: the stuff that nightmares are made of.)

In raw empirical terms, Reminiscence has roughly as many minuses as pluses. Its characters are thin and familiar. Its writing is clumsy and obvious, most painfully in its subplot about a literal underclass that toils in the shadows of the rich and powerful. Its handful of set pieces are sloppily choreographed. And it saddles its hero, Nick (Hugh Jackman), with one of those nonstop explanatory voiceovers, the kind that screenwriting workshops devote entire sessions around when illustrating the axiom of show, don’t tell.

Yet Reminiscence is nevertheless rewarding, often deeply so, thanks to its enveloping aesthetic and its overall grandeur. The production design, by Soderbergh regular Howard Cummings, is especially impressive. Joy sets the film in a near future where climate change has ravaged coastal cities, and the ruined Miami where the events take place is a marvel of watery streets and clogged canals, like an archipelago of skyscrapers. But the movie’s signature achievement is interior. It’s the Tank, the facility inside an abandoned bank where Nick plies his dream-soaked trade. Working with his old war buddy, Watts (Thandiwe Newton), Nick is a professional purveyor of nostalgia; clients eagerly climb into a water-filled cylinder and tell him a memory, which—thanks to some mysterious combination of electric voltage and Nick’s gumshoe intuition—they literally relive, and which play out for us on a ringed dais in the center of the building’s large, airy ground floor.

The interplay between dreams and reality is hardly a novel cinematic conceit, but Joy’s execution here is inspired. Nick, who guides his customers through their fog of memory with soothing prompts, is both a director and an observer, and Joy frequently clouds the boundary between past and present, turning Nick into an unwitting participant in his own production. In one gorgeous shot, he faces the figment of a particularly significant client (Rebecca Ferguson, bringing color to the picture in a parade of high-slit dresses), and the camera captures their profiles, the tortured man staring intently at this enigmatic woman who looks past and through him. And a late sequence, in which Nick tries to supplant the visual echo of an odious gangster (Cliff Curtis), is a wonderful blend of new-age ingenuity and old-fashioned romanticism.

And ultimately, Reminiscence’s poetic sweep overwhelms its more prosaic failings. Logically, the film doesn’t quite track; Joy’s writing is too clunky to imbue her action with the desired emotional heft. (For a superior example of this kind of story, see Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days, which leans beautifully into its own excess.) But conceptually, the movie teems with provocative ideas, and some of its images—a broken piano sinking into a sun-pierced pool, a reconstructed clock shop designed to thwart dementia, a ramshackle sanctuary floating in the ocean—possess independent force. Reminiscence may not work as a piece of drama, but its heady mix—of thriller and weepie, of grit and gloss, of classic emotion and bold imagination—will nonetheless linger in your memory.

Neither Reminiscence nor The Night House is particularly conformist, but both still operate in the standard way we expect movies to function—y’know, with a plot, characters, and dialogue. Not so for Annette, the absolutely bonkers musical from the French director Leos Carax. Every musical is unreal to a certain extent, but this one is defiantly unorthodox, eschewing traditional narrative and instead manufacturing a mood of persistent absurdity. And so: One character sings while performing cunnilingus. Another breaks the fourth wall, only to apologize and briefly return to his on-screen duties. A child’s toy becomes a gateway for a voice from the netherworld. And I haven’t even mentioned the titular puppet baby.

This is Carax’s first feature since 2012’s Holy Motors, the incomprehensible and largely beloved (though not by me) art film whose most memorable scene was a sudden intermission in which its hero randomly strode through a warehouse while playing the accordion, gathering a swell of supporting musicians in his wake. (Sample lyrics: “Three, twelve, shit!”) Essentially, Annette aspires to translate that sequence to feature length, in terms of both its silky craft and its resolute illogic.

It succeeds, which doesn’t necessarily make it a success. By which I mean, Annette is simultaneously a triumph of filmmaking and a failure of storytelling. The cinematography, by the veteran lenser Caroline Champetier (who also shot Holy Motors), is entrancing, most notably for its pervasive use of green; virtually everything in the film—from the forest that surrounds the principals’ nestled home, to the robes and dresses that adorn the characters, to even the water that glows in a fateful pool—is a vibrant shade of emerald. The arresting color(s) and the fluid camerawork amplify the fantastical quality of the images, which often take on a fairy-tale otherness, as when a married couple dance on the deck of a boat that pitches against the waves of a merciless storm.

It’s almost magical. Yet in terms of plot—that pesky aspect of cinema which concerns what happens to the characters, and why—Annette is pretty fucking stupid. Ostensibly, it considers the asymmetrical marriage between a famous opera singer, Ann (Marion Cotillard), and her comedian husband, the ludicrously named Henry McHenry (Adam Driver). But any attempt to divine meaning from the film’s batty structure is pure guesswork. Is it a satire of our unhealthy obsession with celebrities? An allegory of domestic abuse? A rebuke of “cancel culture”? I can’t say, and I can’t imagine Carax cares; he’s too worried about shocking his audience to bother developing his characters or articulating his themes.

Speaking of audiences, the film spends a great deal of time watching Henry’s endless performances, where he endeavors to deconstruct the very notion of comedy, or whatever. The crowds initially laugh riotously before booing lustily, but either way, they seem to be part of the show itself; how else to explain their ability to chant in time to Henry’s rhythmic taunts? If the best way to ruin a joke is to explain it, the surest way to stop a musical in its tracks is for a nominal comedian to deliver a rambling monologue about murderous tickling.

Aside from Henry’s interminable sets, virtually all of the dialogue in Annette is sung. (The screenplay is by the band Sparks, aka Ron and Russell Mael, who also composed the music.) It’s an audacious approach that’s in keeping with Carax’s demented ambition, but the hit rate is low. The opening number, “So May We Start”—one of those casually bravura single-take sequences that follows the characters from a recording studio out into the street, collecting new members along the way—is a hypnotic beginning, but later songs such as “We Love Each Other So Much”—which literally features Ann and Henry cooing the title to each other over and over—are forgettable. (I’ve heard people likening the movie to La La Land, and while there are glancing similarities—technical magnificence, artistic aspirants wrestling with their careers—I find the comparison offensive.) As for the performances, Driver isn’t much of a singer, but he suitably conveys Henry’s dark intensity; for her part, Cotillard’s usual luminosity feels oddly diminished, perhaps because of the flatness of the role.

But what about Annette herself? With a body of wood and the voice of an angel, her preposterous ascension to stardom allows the film to acquire a sliver of dramatic interest, beyond its gonzo trappings. And in its final scene—a gripping duet between Henry and his suddenly changed offspring—Annette threatens to become genuinely moving. I can’t quite say it overpowered me, and I remain suspicious that this routinely dazzling, utterly bizarre movie is thematically and morally vacant. But that doesn’t make it worthless. So maybe Henry’s cackling audiences were on to something, laughing hysterically at things that aren’t funny. This emperor may have no clothes, but the fabric sure is stunning.

The Night House grade: B-

Reminiscence grade: B-

Annette grade: B-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.