During one of the many ruminative exchanges in David Lowery’s The Green Knight, a common young woman scoffs at her paramour’s obsession with greatness. “Why is goodness not enough?” she wonders with a combination of selfishness and curiosity. Like most of its maker’s movies, The Green Knight operates—or attempts to operate—as both a sincere answer to the question and an emphatic rejection of its premise. In films like the Malick-infused crime drama Ain’t Them Bodies Saints and the austere metaphysical puzzler A Ghost Story, Lowery wasn’t aiming for passable entertainment; he wanted to make high art, true masterpieces that reshaped our attitude toward what cinema can be. (His Ghost Story follow-up, The Old Man & the Gun, was enjoyable in part for how atypically relaxed it was.) Judged against that impossible standard, he failed both times, and does so again here; The Green Knight is no masterpiece. But it is undeniably a mighty work, and its towering ambition—the way it takes an epic poem and updates it with its own combination of beauty, whimsy, and nonsense—is itself commendable.

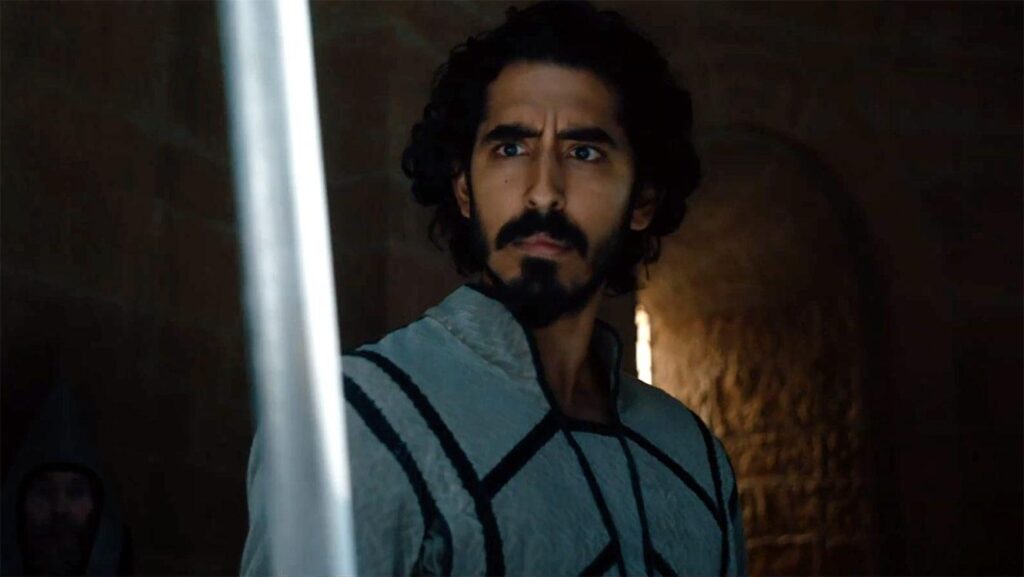

The title of that poem, “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” (by Anonymous), briefly emerges on screen, in an Old-English font that’s nigh unreadable; over the course of the proceedings, other headings make similarly quick appearances, each harder to decipher than the last. In fact, illegibility is something of a precept for the movie, be it vocally, visually, or narratively. Actors often mumble lines, their “thees” and “thines” drowned out by the clangs of nature or Daniel Hart’s moody score. The image, especially in the opening scenes, is often dark, as though a fog of war has settled over the screen. And the trajectory of the story, which follows Gawain (Dev Patel) on a picaresque adventure, is regularly interrupted by strange sights and odd digressions.

None of this is accidental. Rather, obscurity is one of Lowery’s tools, a device he wields to draw you in to the picture’s sinister world and to deepen its mysteries. For all its eye-catching splendor, The Green Knight occasionally feels less like a movie than a vibe. Conversations quaver with unspoken longings and double meanings. Pieces of cloth become totems of vitality. Ghosts walk, and animals talk. “You’re not very good with questions,” a man teases Gawain at one point, and his mockery is both accurate and misjudged; it’s more that Lowery is not very interested in supplying answers.

This doesn’t mean the film disdains familiar themes; to the contrary, it traffics in hoary medieval concepts like honor, duty, and hubris (not to mention the most ubiquitous human weakness of all myths: forbidden lust). Its inciting incident occurs when its titular warrior, portrayed with eerie menace by Ralph Ineson under coats of impressive prosthetics, arrives at Camelot and challenges those seated at the famed round table to “a game”: any knight who can whack him shall win temporary custody of his fearsome battle-ax, but in exchange the victor must venture north to his Green Chapel in one year’s time and see the blow repaid. Now, this reciprocal offer does not strike me as especially enticing. But Gawain, dispirited upon realizing that he has no tales of valor with which to regale his considerate king (an unusually gentle Sean Harris), leaps at the chance and decapitates this colossal he-man, whose body then promptly bends down and picks up its own noggin, seemingly unharmed. Gawain (pronounced GAR-win), despite being the proud owner of a shiny new weapon, is less than overjoyed, seeing as he’s now headed for a beheading.

What follows is an episodic journey that’s less memorable for what happens than for how it happens. Lowery gives his regular cinematographer, Andrew Droz Palermo, ample latitude to experiment, and he obliges with images that are arresting for both their classicism and their verve. Though the movie’s early scenes are quite dim, its palette brightens over time, with different environments receiving their own color scheme; in one sequence, Gawain rides through a dusk that breathes with an ominously yellow hue, while in another, he dives into a pool whose water suddenly pulses with a dull red glow. Much like its plotting, the film’s visual construction is patient, as in a spellbinding moment where the camera rotates away from a bound-and-gagged Gawain and slowly revolves 360 degrees to rediscover him as an apparent skeleton, then reverses course and recircles, finding him alive once more.

What does that shot mean? The Green Knight shuns such an inquiry as prosaic; to pose it is to reveal yourself as a rube. Yet it seems only fair to interrogate the movie’s enigmatic nature, and to wonder if it shrouds itself for any greater purpose beyond academic inscrutability. Over the course of his travels, Gawain encounters a number of peculiar folk, all of whom presumably have Something To Say about the meaning of life. He is waylaid by a chatty scavenger (Barry Keoghan, reliably disreputable), encounters a redheaded woman (Erin Kellyman) who may be a ghost, and takes shelter at the castle of a friendly lord (Joel Edgerton), whose wife (Alicia Vikander) looks suspiciously like Gawain’s lowborn lover. These scenes are independently interesting—Vikander gets to make an impassioned speech about the title color, and also to engage in passion of a more robust and chilling sort—without adding up to much of anything. Perhaps such unknowability is the point, an idea that crystallizes when Gawain asks the ethereal redhead whether she’s real or a spirit, and she responds, “Does it matter?”

I would argue that it does. My quarrel with The Green Knight isn’t that it refuses to “make sense” in any traditional manner. It’s that Lowery never bothers to imbue his collage of prettified weirdness with any articulable theme. Some may deem such abstention virtuous, as it allows viewers to imprint upon this blank canvas the message of their choice. But I find the film’s vagueness less tantalizing than irritating. It delivers plenty of intrigue—an upside-down painting, a startling kiss, a bizarrely attuned fox, a woman (Sarita Choudhury) who seems to be both puppet master and sorceress—but it never assembles its eccentricities with any cohesion. Lowery may think his commitment to ambiguity as a storytelling principle is noble, but it strikes me as a childish form of defiance.

And yet, as he flaunted in A Ghost Story, Lowery is still exceedingly capable, especially when it comes to endings. In its final scenes, as if by miracle (or perhaps by the hand of one of those giants roaming across the wilderness?), The Green Knight shrugs off its own elusiveness and acquires kinetic, elemental force. It’s a remarkable passage—mostly wordless, racing through time but nonetheless telling a sweeping and elegiac fable in a matter of minutes. Of course, while it’s thrilling cinema, whether it fully redeems the film’s prior flaws is an open question. I suppose that’s only fitting. After all, in a movie as deliberately knotty and perplexing as this, discerning whether it’s good or bad becomes just another unsolvable mystery.

Grade: B-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.