Among the innumerable genres represented in Everything Everywhere All at Once—the universe-hopping, tone-mutating, brain-scrambling whatsit from Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (collectively known as Daniels)—is the martial-arts instruction picture. Like Ralph Macchio in The Karate Kid and Uma Thurman in Kill Bill, its protagonist receives tutelage from a wiser, more experienced combat veteran. But here, rather than preaching about the virtues of discipline or the importance of practice, the seasoned mentor encourages our hero to weaponize absurdity. “The less sense it makes,” he insists, “the better.”

This is a matter of opinion, at least when it comes to movies. At the cinema, the twin values of logic and imagination are often in tension with one another, resulting in an artistic seesaw in which adding weight to one sacrifices the other. The brilliance of Everything Everywhere All at Once isn’t that it strikes the perfect balance between these qualities but that it loads up so heavily on one as to render the other irrelevant. Here is a work of bold, boisterous originality, teeming with rich ideas and vivid images and the quixotic thrill of genuine inspiration. It isn’t better because it doesn’t make sense. It’s better because it redefines the concept of making sense entirely.

Despite its title (which it means more literally than you might expect), Everything Everywhere takes awhile before revealing the full breadth of its maniacal ambition. Its opening scenes are instead a flurry of domestic bustle and commercial aggravation, suggesting a hectic but intimate family melodrama. Evelyn (Michelle Yeoh), its weary and vibrant center, is a harried laundromat owner beset by personal and professional problems. She’s anxious about throwing a party for her aging father (James Hong), who can convey decades’ worth of generational disapproval with a single, withering glance. Fear of antagonizing him leads Evelyn to closet her gay daughter, Joy (Stephanie Hsu), who understandably resents her mother’s latent bigotry and laments her lack of backbone. Meanwhile, Evelyn’s husband, Waymond (the delightful Ke Huy Quan), flutters nervously on the periphery, and their strained exchanges—along with the ominous appearance of an unsigned document titled, “Petition for Dissolution of Marriage”—imply an irreconcilable conflict. And a different sort of existential threat looms in the form of Deirdre (Jamie Lee Curtis), an unsmiling IRS auditor who is combing through Evelyn’s finances with pitiless rigor and a perpetual scowl.

Daniels map out these character dynamics swiftly and efficiently—and good thing too, given how much additional material they have in store. The first hint that something is gleefully amiss arrives during an early glimpse of a bank of cruddy surveillance monitors, where we see a shuffling character inexplicably straighten his posture and leap purposefully onto a washing machine. Not long after, Waymond—who, with his meek voice and deferential bearing, is the quintessential beta male—suddenly transforms into a literal alpha; his consciousness, he breathlessly explains to a thunderstruck Evelyn, has travelled to this unremarkable realm from the Alpha Universe, where…

But I shouldn’t say too much. Or maybe I can’t. Daniels have constructed Everything Everywhere with dizzying attention to detail, but they have also concocted a storyline that defies logical description—or at least that makes any description sound illogical. Expect, perhaps, to label the film a spiritual cousin to The Matrix. Like Keanu Reeves’ baffled hero in that epic franchise, Evelyn learns that she is a messianic figure whom all of humanity is depending on for their very survival. Aided by a ragtag group of upstart rebels—in addition to Alpha Waymond’s bursts of expository guidance, we periodically see a bunch of weirdos in a van fiddling with gizmos and chattering instructions into headsets—she must master her newfound abilities and do battle against a fearsome, malignant heavy who’s hell-bent on the world’s (or worlds’) destruction.

Naturally, it isn’t quite that simple; in fact, it isn’t remotely simple. Yet the genius of Everything Everywhere is that its cockamamie premise—Evelyn is capable of tapping into parallel selves (a Kung Fu actor, a sign-spinner) and exploiting their peculiar abilities for her own desperate ends—functions as a launching pad for its makers’ restless whimsy and freewheeling creativity. The result is a parade of glorious nonsense which, in its own bizarre way, carries a certain artistic integrity. The movie spirals off in infinite directions (remember: multiverse), yet it still maintains a consistent through line, a governing principle of scrupulous lunacy.

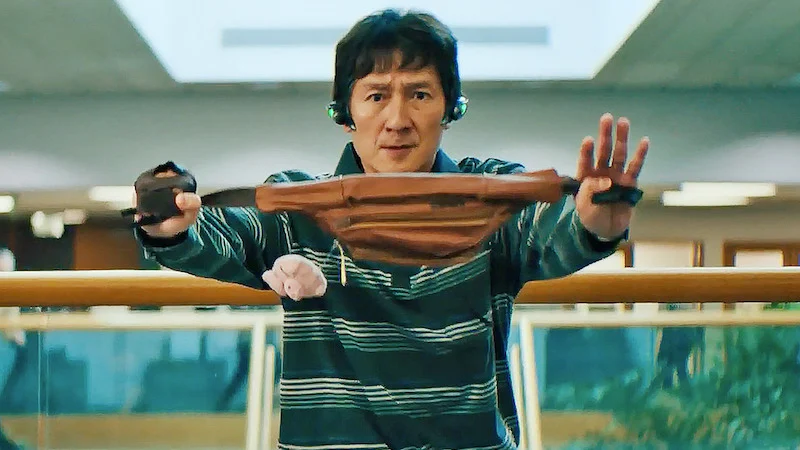

Everything Everywhere careens madly (though not quite randomly) between genres—it is by turn a science-fiction thriller, a marital drama, a mother-daughter bickerfest, a madcap comedy, and more—but its greatest triumph is as an action movie. Despite their relentless invention, Daniels—whose prior collaboration, Swiss Army Man, was an utterly deranged adventure that now feels positively mundane by comparison—are unusually disciplined fight choreographers, and their combat scenes pulse with kinetic clarity. Of course, the particulars of these mayhem-filled moments remain thoroughly gonzo. In one joyous sequence, Waymond dispatches a troop of security officers by wielding the world’s deadliest fanny pack; in another, Joy makes mincemeat of her overmatched pursuers via a pair of bloody dildos. And that Auditor of the Month trophy which sits on Deirdre’s desk and looks suspiciously geared for penetrating a certain orifice? You don’t want to know.

The constancy of the chaos is occasionally exhausting—there are perhaps a few too many scenes set in a perverse universe where fingers have been replaced by hot dogs—but Daniels have more on their mind than simply assaulting their audience with crisply calibrated goofiness. They are also attempting to mount a serious thematic argument. The nominal villain of Everything Everywhere is a malevolent, all-consuming being called Jobu Tupaki, who strides through the scenery in an array of magnificent, glittering costumes, and who seems to have targeted Evelyn for specific retribution. Yet the real forces of evil whom Evelyn must defeat aren’t bad people but bad feelings—in particular a suffocating combination of depression, isolation, and shame. To save humanity, she must first save her family, which means she must conquer this confluence of misery—visually represented, in yet another inspired touch, as a giant everything bagel—by drawing on the powers of acceptance and compassion.

The challenge for Daniels is to connect their idiosyncratic zaniness—the loopy strangeness that contemplates an alternate version of Ratatouille featuring a raccoon, and that makes significant totems out of googly eyes—with an emotional message that is fundamentally corny. I am not entirely sure they pull it off. The film’s central notions—be kind to each other, embrace your children—can feel trite as well as poignant. I suspect that there’s a different multiverse out there where Everything Everywhere’s wild ingenuity integrates more gracefully with its inherent tenderness.

This isn’t to say that the film is insufficiently moving, in both senses of the word. Daniels are fiercely committed to their characters’ individuality, and while the fraught relationship between Evelyn and Joy is suitably heartrending, the stealthy soul of Everything Everywhere is Waymond. He’s kind of a mess—struggling to communicate with his wife, demeaned by his father-in-law, diminished by his daughter—but he behaves with an abiding sweetness that goes beyond basic decency; it’s also a potent rejection of the seductive nihilism that threatens to overwhelm everyone he holds dear. Quan, forever known as Indiana Jones’ sidekick in The Temple of Doom, imbues Waymond with a simple goodness that’s overpowering in its sincerity. Sure, there’s a ludicrous (and painful!) scene where he gives himself paper cuts in order to access certain gifts, but that sacrifice reveals just how deeply he’s committed to his family. And once you look at Everything Everywhere All at Once through that lens—as a crucible of loyalty and love—then this giddy, unhinged, wonderful movie starts to make an awful lot of sense.

Grade: A-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.