What scares you? More to the point, what kind of movie scares you? It’s been 100 years since Max Schreck climbed out of his coffin in Nosferatu, and directors have been harnessing and refining cinematic tricks to terrify their audiences ever since. One of the pleasures of the horror genre is its versatility—its infinite methods for exploring madness. This past weekend featured the release of two creepy pictures that take decidedly different approaches in their similar effort to raise the goose bumps on your arms and the hackles on your neck. One tries to dig under your skin; the other carves your skin clean off.

David Cronenberg is the father of modern body horror—or maybe the grandfather, given that the Canadian envelope-pusher is now 79 years old. But the director’s latest grotesquery, the arresting and impressive and ultimately empty Crimes of the Future, proves that age hasn’t sapped him of his enthusiasm for staging imaginative corporeal brutality. In the film’s opening scene, an eight-year-old boy living off the coast of a Grecian island munches on a plastic wastebasket, swallowing its synthetic fibers with no apparent difficulty; shortly thereafter, his mother smothers him to death with a pillow. This shocking, vulgar sequence is arguably the least inexplicable thing that happens in the entire movie.

For Cronenberg, vulgarity is not purely a matter of provocation. He has spent much of his five-decade career subjecting his characters to inhumane (and often literally inhuman) punishment, not as an exercise in sadism but in a sincere inquiry into the human body’s potential for change and expansion. This is his first feature in seven years, and it follows a brief philosophical detour in which he examined the ravages of capitalism (in the dreary Cosmopolis) and the crassness of celebrity (in the dreadful Maps to the Stars). Crimes of the Future, with its drillings of bone and distensions of muscle—it conceives of a world where people spontaneously grow and excise new organs—marks the director’s return to physical substance, if not to actual form.

Despite its narrative weaknesses—as a storyteller, Cronenberg once again proves indifferent to basic elements of plot and character—Crimes of the Future is a notable achievement of misshapen design; rarely has a motion picture been so vividly, creatively nauseating. Set in an unspecified but assuredly bleak future, its main character, Saul (a sturdy Viggo Mortensen), sleeps on a suspended bed that looks like a dinosaur’s carcass, with sinewy claw-like arms protruding from the ceiling and jutting into his wrists. When he eats, he sits in a skeletal chair that buffets his neck and arms like a hygienist from hell, preventing his fork from reaching his mouth. He and his partner, Caprice (Léa Seydoux), own an autopsy machine whose ghastly instruments they control by operating a squishy remote that looks like a gizzard, its black surface concealing flashes of darkly colored light within. Compared to other demented figures we meet, Saul and Caprice are the normal ones; they do not, for example, sew severed ears all over their arms and stomach, nor do they munch on purple candy bars made of plastic.

This stuff is undeniably gross. But it is at least evocatively gross; accentuated by Howard Shore’s doomy score, Cronenberg’s bizarre monstrosities leap from a dark place of genuine curiosity. They can also yield perversely memorable scenes. The sequence where Caprice performs surgery on Saul in front of a crowd of fascinated onlookers (they’re performance artists, you see) is a foully gripping medley of slicing blades and exposed flesh, while the moment where an overeager bureaucrat (a game Kristen Stewart) impulsively thrusts her fingers inside Saul’s mouth is hypnotically weird.

I wish I could tell you that Cronenberg connected his strikingly repulsive images to a set of correspondingly inflammatory ideas. Alas, the opposite is true. Thematically, Crimes of the Future is a work of pseudo-profundity, a stiff and awkward parade of the same intellectual psychobabble which doomed Cosmopolis. Throughout, characters discuss supposedly weighty issues such as human evolution, environmental catastrophe, and erotic desire. (Stewart’s line reading of “Surgery is the new sex” has already stormed the internet—no matter that it means nothing.) Most of the dialogue is stilted and unconvincing, like footnotes from a student’s term paper randomly inserted into a crude videogame. These ponderous exchanges diminish any prospect of philosophical gravity, instead lending the film a studied, pompous air.

This intellectual vacuity might be more forgivable if the movie nonetheless gathered narrative momentum. But unlike in A History of Violence or Eastern Promises, where Cronenberg channeled his incendiary antics into dramatically engaging stories, Crimes of the Future has no interest in urgency or coherence. There is the specter of a mystery involving a cop, a renegade, and a pair of murderesses who periodically waltz onto the screen with wide smiles and enigmatic agendas. None of it makes any sense, and I’m not sure it’s meant to; Cronenberg cares far more about jangling nerves than building intrigue.

A compelling plot isn’t a prerequisite for an engrossing movie, but Crimes of the Future’s refusal to tell a lucid story scans less as tantalizingly ambiguous than artistically lazy. The shame of this apathy is that it squanders a committed lead performance from Mortensen, who uses his fearsome physicality to amplify Saul’s anguish. (For her part, Stewart seems to understand that nothing can be understood, and she ignores emotional legibility in favor of raw intensity.) This is Mortensen’s fourth collaboration with Cronenberg—following the spectacular one-two genre punch of Violence and Promises, he played Freud in the underrated A Dangerous Method—and it’s the first time his natural charisma has been overwhelmed by his director’s shameless showmanship. Cronenberg continues to wield his ugly flair to punish our bodies, but in doing so, he starves our minds.

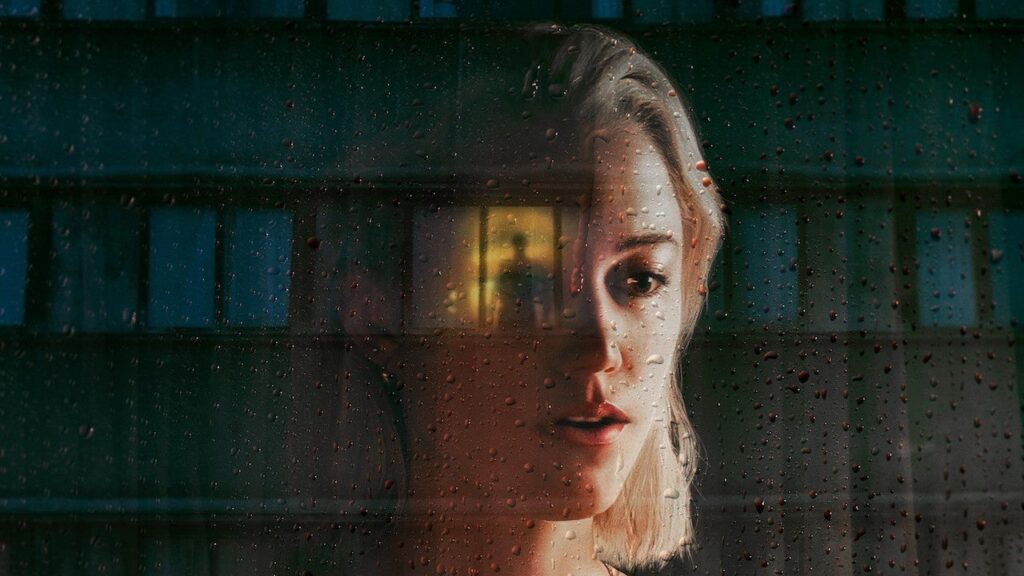

Watcher, the feature debut of Chloe Okuno, belongs to a different school of horror filmmaking. It is a smoother and more patient creature, disdaining garish violence and aggressive shocks in favor of sustained creepiness and psychological terror. Crimes of the Future may pile on the vivisections and bloody organs, but for sheer suspense, it can’t hope to match the moment in Watcher when Maika Monroe freezes with fear as an unknown figure takes his seat behind her in a movie theater.

Monroe, you may or may not recall, made her bones last decade as a so-called “scream queen” in the superior chillers The Guest and It Follows. Her career never received the stardom bump it deserved (she’s quite good in the silly Greta), but here she slyly leverages her experience. Her character, Julia, is an American expat newly settled in Bucharest, where her husband (Karl Glusman) schmoozes at a white-collar gig while she languishes in their handsome apartment and struggles with the language barrier. Julia spends most of Watcher in various states of fright, and Monroe leans into her innate gift for articulating anxiety while supplementing it with layers of strength and steel.

She’ll need them. Or maybe she’s just seeing things. Much like 2020’s The Invisible Man, Watcher is a movie about a woman afraid of a man, which means everyone else in her orbit deems her paranoid or hysterical. Whiling away the solitary hours with little to occupy her restless mind, Julia becomes convinced that the dude who lives across the street is constantly watching her from his window. (The title is a virtual homophone for “watch her.”) Meanwhile, a serial killer dubbed “The Spider” is decapitating girls in the neighborhood. Has Julia laid eyes on the perpetrator? Or is she a hyperactively imaginative troublemaker whose senseless fretting keeps interfering with her frustrated husband’s career? Does it make a difference that her possible stalker takes the inherently disturbing form of the English actor Burn Gorman? Do you know what gaslighting is? Last question: Does Chekhov’s law apply to guns discovered in the second act?

The premise of Watcher isn’t especially complicated; it’s yet another vaguely Hitchcockian exploration of how the innocuous pleasures of voyeurism can curdle into the noxious fumes of suspicion. What makes it (ahem) watchable, beyond Monroe’s silkily magnetic performance, is Okuno’s masterful choreography. She and her cinematographer, Benjamin Kirk Nielsen, understand how to convey the mutuality of eye contact: If you’re looking at someone, they’re just as likely to be looking at you. The best scenes in Watcher imbue that fundamental principle with a visceral, heart-pounding kick. Camera placement is key; much like M. Night Shyamalan, Okuno favors tight close-ups of Monroe’s face to emphasize the narrowness of her field of vision, which she then communicates through carefully framed point-of-view shots. The result is that ostensibly simple sequences of Julia just looking around—whether at the movies, on the subway, in her apartment, or (most memorably) at the grocery store—seethe with agonizing tension and trepidation.

The vast majority of Watcher is so enveloping—just look at Monroe’s face when she realizes that she’s been the butt of one of her husband’s Romanian jokes, and marvel at how fluidly her posture shifts from ingratiating to icy—that its final scenes are a bit deflating. To be fair to Okuno, who based her screenplay on a script originally penned by Zack Ford, it’s difficult to wrap up dread-accumulating movies in a satisfying way. (This is one of many reasons that It Follows is so exceptional.) Still, she arguably makes the opposite mistake that fells Cronenberg in Crimes of the Future, cleanly sweeping up the film’s tendrils of possibility and repackaging them into an overly tidy resolution.

All the same, Watcher remains a supple and invigorating work, coursing with energy and craft; even its dubious finale manages to supply a breathtaking shot in which two adversaries at long last stare into each other’s eyes, mirror images of power and desire. Crimes of the Future may provide the more ghoulish and exotic displays of stomach-churning bloodletting. But it’s Watcher’s smooth technique—and Monroe’s mounting desperation—that prevent you from ever looking away.

Crimes of the Future grade: C+

Watcher grade: B+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.