Ah, the ’80s: that glorious decade of unvarnished patriotism, jubilant synth music, and pop-culture cheese. As artifacts of this ancient era go, Tony Scott’s Top Gun has aged more poorly than most; it now plays as a silly, occasionally diverting genre exercise that doubles as a military recruitment ad, and while it entertains as a tribute to the glistening machismo of Tom Cruise, it also suffers from thin characters and a profoundly stupid story. So when I tell you that Top Gun: Maverick, the 36-years-in-the-making follow-up directed by Joseph Kosinski (from a script credited to Ehren Kruger, Eric Warren Singer, and Christopher McQuarrie), improves on its predecessor in every conceivable way, what I really mean is, it’s not bad.

Honestly, that assessment is perhaps unfair to Kosinski and Cruise, who have approached this legacy assignment with a canny combination of reverence, intelligence, and playfulness. Not content with merely avoiding stupidity, Maverick is often genuinely smart. Its character dynamics are sharp, its plot makes structural (if not geopolitical) sense, and its action is mostly engaging and occasionally electrifying. It’s a pretty good movie that also wrestles with the obligation of being a Top Gun sequel.

And there is a bit too much of that. The initial moments of Maverick, which begins with the exact same explanatory crawl that opened Scott’s picture (just in case you forgot the basis for the film’s title) and follows it with faux-euphoric footage of jets launching from an aircraft carrier, portend a sequel that is feverishly beholden to its original. Thankfully, Kosinski proves adept at tweaking the franchise blueprint rather than copying it, interrogating some of its muscular traditions even as he commits to providing another rush of adrenaline. Still, much of the insistent echoing—the constant micro-flashbacks, the triumphant motorcycle rides, the intractability of the hard deck, the murmurs of “Talk to me, Goose”—comes off less like a course correction than a dutiful autopilot tracing an identical route.

But about those tweaks: Where the plot of the first Top Gun was threadbare and clumsy—it essentially involved egotistical flyboys competing to score literal points, then tacked on a “real” military campaign whose details were hazy and absurd—the narrative of Maverick flows with pleasing momentum and carries actual stakes. Yet again, a band of scrappy and cocky pilots have gathered in sunny California, but rather than vying for precious trophies, they’re training for a real mission—one which, should they choose to accept it (sorry, wrong franchise), features defined challenges and tangible risk. (The nation housing this sinister enemy base goes strategically unnamed; the film possesses no political agenda beyond being vaguely pro-American.) But who is going to prepare these gifted upstarts for such a dangerous operation? If only there were a legendary aviator available, a hotheaded captain who once felt the need for speed…

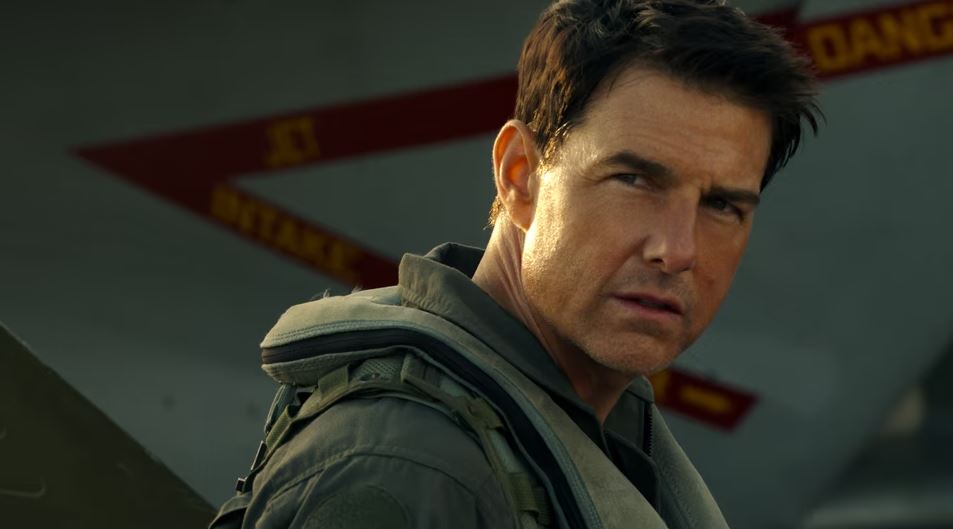

The character of Pete “Maverick” Mitchell by no means defines Tom Cruise’s legacy; he is too ambitious and nervy an actor to be forever tied to one of his most memorably smirking dipshits. Nonetheless, it’s fascinating to revisit this volleyball-smashing goofball, and to consider how he and the maniacal man playing him have and haven’t changed in the intervening decades. Cruise, alongside Christopher Nolan, has emerged as our foremost champion of the theatrical experience, exalting motion pictures as big-screen productions and continuing to do his own increasingly perilous stunt work even as he pushes 60. (He cracks the sexagenarian mark next month, though shooting here was completed in 2019 before pandemic-inspired delays.) Maverick, meanwhile, seems to have carved out an amorphous employment zone in the U.S. Navy, failing (or declining) to receive promotions yet still ostensibly commanding a stealth-bomber program. There’s plenty of separation between the two alpha males, but it doesn’t require a ton of thread to connect the dude who always runs in his movies to the dude who’s desperately trying to crack Mach 10.

Thematically speaking, Maverick hardly uncovers new territory. As befits his call sign, its title character remains a rebel (“Your ego’s writing checks your body can’t cash!”), a system-bucking iconoclast whose refusal to follow the rules and abide by chain of command chafes the stern, conformist establishment; this anti-fun bureaucracy is personified first by Ed Harris—who plays an admiral derisively dubbed the Drone Ranger, a man who imagines a sterile future in which all planes are automated and human pilots are extinct (kindly insert your meta cinematic take here)—and later by a reliably grouchy Jon Hamm. (One of the movie’s instantly classic images is the shot of Harris looking up disapprovingly as a sleek jet zooms over his head.) This inherent conflict—cowboys vs. pencil-pushers, improvisation vs. formula, man vs. machine—is not exactly novel. What’s more intriguing is how Maverick must channel his anarchic instincts into team-building—a task made more complicated when he discovers that one of his pupils, Rooster (Miles Teller), is the son of his late navigator, who died tragically during the first film. Rooster, curiously enough, isn’t a fiery gunslinger like his instructor but a more conservative tactician; Maverick seems more likely to locate a spiritual kinship with Hangman (a very fine Glen Powell), a brash and braggadocian flyer who seems more interested in superiority than camaraderie.

Kosinski labors to illustrate these temperamental differences not simply through dialogue, but with an array of dynamic, elaborate flight sequences. My screening of Maverick was preceded with an appreciative direct-to-camera address from Cruise, thanking viewers for returning to theaters and assuring us that the ensuing picture features “real speed” and “real Gs.” He wasn’t lying. Kosinski, who previously directed Cruise in the underrated Oblivion, plainly shares his star’s love of real-world, body-punishing action. The aerial scenes here possess credible weight, along with a whooshing velocity that appropriately conveys the absurdity of men (and women! One of the pilots is a feisty femme called Phoenix, played with spunk and grace by Monica Barbaro) strapping into a tiny cockpit and launching themselves thousands of feet into the air.

And yet… is the movie’s action legitimately exciting? It’s impressively realistic, sure, but realism doesn’t necessarily translate to exhilaration; that the actors actually experienced the intensity of heightened gravitational force doesn’t change the fact that capturing such force involves little more than straightforward shots of them wincing in pain. There is quite a bit of frantic knob-twisting and stick-jerking, and the characters constantly shout things—break right! I can’t see him! watch your six!—but there is limited flair to the broader choreography. This disconnect between physical achievement and cinematic enjoyment is most evident during an early scene where Maverick pushes his jet to unprecedented speed; in real life, the plane is presumably going quite fast, but from the theater, all we’re really doing is watching an LED display tick up from one decimal point to the next.

I don’t mean to minimize the cast and crew’s audacity—and to be clear, the cleanly edited dogfights on display here are more enveloping than the green-screened laser shows that accompany most modern superhero flicks—but to acknowledge the bizarre nature of Kosinski’s accomplishment; he has made a deeply satisfying sequel to Top freaking Gun even though his set pieces are solid rather than magnificent. The trick, strangely enough, lies in the characters. In grappling with his own looming obsolescence, Maverick is a more soulful presence this time around, and Cruise deftly threads the needle between contemptuous hothead and wise veteran; the touching scene where he visits his old rival, Iceman, is the best kind of self-reflexive nostalgia, and not just because it’s wonderful to see Val Kilmer on screen again. The young guns, meanwhile, are an agreeably motley bunch; the inevitable clashing of their disparate personalities calls to mind a classical platoon picture, while their shirtless beach football game is a deliriously fun update to the (in)famous volleyball contest of the original.

Yet the most significant new presence, despite Powell’s slyly disreputable turn as Hangman, isn’t an aviator at all. It’s Penny, the tart and wry bar owner who eyes the prodigal Maverick the way a shark eyes chum. (Scholars of the original will recognize Penny’s name from an offhand line of dialogue about an admiral’s daughter; Maverick’s prior love interest, Kelly McGillis’ Charlie, goes unmentioned.) As played by the innately luminous Jennifer Connelly, Penny is Maverick’s emotional and intellectual equal rather than a mere object of his pursuit, and their brief courtship pulses with genuine ardor; a scene where she takes him out in a catamaran (“I thought you were in the Navy?” “I don’t sail boats, I land on them!”) is a joyous piece of adult flirting (complete with the gorgeous shot of a billowing blue sail), while a beautifully orchestrated silent goodbye brought tears to my eyes.

And there’s something weirdly moving about Top Gun: Maverick, a dopey earnestness that feels sincere rather than mercenary. The image of Tom Cruise once again climbing into the cockpit of an F-14 should feel cannibalistic, but as staged by Kosinski during the predictable yet effective climax, it carries an undeniable charge. The logical fear here was that this movie would simply recycle the original’s sun-baked jingoism, but it turns out to be performing its own kind of boldly inverted dive. Its body writes the checks; its superego cashes them.

Grade: B

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.