Listen up, kids, here are some dos and don’ts courtesy of The Black Phone, the grimy new horror movie from Scott Derrickson: Do stand up to bullies by hitting them in the head with rocks. Don’t beat your children with a belt, even if you’re really just a sad dad on the inside. Do pay careful attention to your dreams, which may or may not be premonitions. Don’t invite the cops inside your home while lines of cocaine are visible on your coffee table. And if a dude in clown makeup driving a black van branded “Abracadabra” approaches you on a vacant sidewalk, do immediately walk the other way; don’t—seriously, do not—ask if you can see a magic trick.

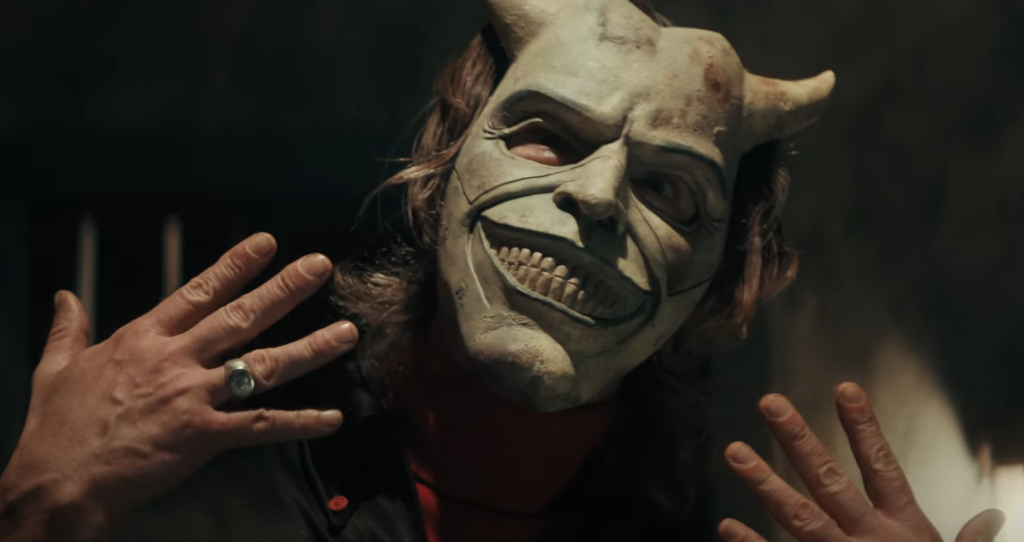

That last nugget comes courtesy of The Grabber, a serial killer terrorizing a morose Denver neighborhood in 1978. With lank hair and dark eyes that peek out from behind a two-piece mask—the upper part topped with devilish horns, the lower forming a demented smile—he’s played by Ethan Hawke, continuing the actor’s not-unwelcome veer into villainy following his small-screen turn on Marvel’s Moon Knight. There are moments of real menace in Hawke’s performance here; when he smothers a child’s cries and threatens to gut him like a pig before strangling him with his own intestines, you know he means it. For the most part, though, he keeps things in second gear, gesturing toward evil rather than embodying it.

That sense of intermediacy applies to the movie as a whole. The Black Phone is modestly entertaining, with one killer set piece and a clammily oppressive atmosphere. Yet it feels like a half-measure, declining to dig into the psychology of its damaged characters and struggling to sustain an ambiance of true dread. It traffics in dark deeds but comes off as lite horror.

Not that there’s anything cheerful about its tone or subject matter. A classic kid-in-peril picture, The Black Phone centers on young Finney (Mason Thames), a glum and diffident youth who’s defined mostly by the abuse he receives, whether from thuggish bullies at school or from his alcoholic father (a helpless Jeremy Davies). The lone bright spot in his life, and in the movie, is his supportive sister, Gwen (Madeleine McGraw), the kind of plucky character whose exaggerated bravado makes you wish the film centered on her. When two dour detectives visit Gwen at school and interrogate her about a recent string of disappearances, her tart reply—“You dumb fucking fart-knockers!”—creates a refreshing jolt of spiky energy.

Unfortunately (for him and for us), Finney is separated from Gwen once The Grabber seduces him with black balloons and flings him into his van, at which point the movie gets down to its bleak, dirty business. Derrickson, returning to his low-budget horror roots after going corporate with Doctor Strange, knows how to set a scene and establish a location (the Fincher-flavored title sequence throbs with danger); the dank basement that Finney finds himself locked in carries the stench of past death, to the point where you expect to see rotted fingernails littering the floor. Its lone amenity, aside from a grubby mattress and bolted door, is the antiquated device of the title, which isn’t plugged in but which nevertheless starts ringing (in a clever touch, when unanswered the phone emits a continuous wail rather than the standard periodic peal); once Finney answers, he learns that he’s somehow able to converse with his captor’s prior victims.

Derrickson, who wrote the screenplay with C. Robert Cargill (adapting a short story by Joe Hill), is appropriately skimpy with exposition; we never uncover the mechanics behind the phone’s supernatural operation, nor do we learn why The Grabber is such a sicko. Instead, The Black Phone unfolds as a series of practical challenges. Using little more than his wits, his nerve, and his inexplicable landline to the past, Finney must devise an escape from his confinement before his sadistic jailor stops playing with his food. Can he use that loose tile to tunnel under the floor? Can he fashion that stray cable into a rope to help him reach and dismantle a barred window? That freezer seems oddly positioned—can he use it to muscle through the wall and break on through to the other side?

This life-and-death game of cat-and-mouse is orchestrated reasonably well, but not quite well enough. With the exception of one suspenseful sequence—in which Finney quietly inputs various permutations into a combination lock while his slumbering guard lurks nearby—Derrickson’s staging is blunt and unimaginative. He throws in the occasional lazy jump-scare, as when one of Finney’s deceased compatriots suddenly appears behind him (the score obligingly screeches in response), but he fails to cultivate visual or dramatic tension. To the extent the film is scary, its shocks are more tired than inspired.

Still, The Black Phone is better as a pure thriller than as any sort of morality play or fable. When it isn’t chronicling the nuts and bolts of Finney’s escapade, it strains to develop a dubious thematic throughline centered on his crippling weakness. (Gwen is made of stronger stuff, whether she’s cracking one of her brother’s tormentors in the noggin with a cinderblock or responding to an unanswered prayer with the line, “Hey Jesus, what the actual fuck?”) To evade the same dreary fate that claimed so many other children, the passive Finney must toughen up and show some backbone for once. “Today’s the day you finally stand up for yourself,” an invisible comrade informs him. Turns out the trick to defeating a hulking psychopath isn’t intelligence or ingenuity but manhood. That’s ironic for this movie which, despite its nominally mature content—dead kids, constant profanity, ghastly violence—is ultimately childish.

Grade: C+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.