Ratings are currency. The brunt of criticism, whether you’re writing it or reading it, is words, and words are work. In our entertainment-glutted present, when countless pieces of art compete for your precious time—there is always a new show to binge, a new game to play—people crave a shorthand to cut through the noise. And so, regardless of the specific metric—four stars! C plus! 9 out of 10 fireball emojis!—ratings function as a useful communicative shorthand, crudely but efficiently reducing a critic’s detailed ruminations to a digestible letter or number. Set against this quant-obsessed backdrop, it’s understandable that Rotten Tomatoes, the review-aggregation giant which assigns a “score” to every movie that’s meant to convey its percentage of positive appraisals, has grown to dominate contemporary cinematic discourse. But while the site’s cultural ubiquity may be explicable, it’s also unfortunate, because Rotten Tomatoes is fucking awful.

Actually, it’s worse than awful; it’s meaningless. And even worse than meaningless, it’s distortive. Rotten Tomatoes purports to answer a straightforward question (“Hey, is this movie any good?”), yet in the process it misleads viewers and, more crucially, reframes discussions. The lifeblood of criticism is conversation: the dialectical exchange of opinions and the robust expression of ideas. Yet under the dominion of Rotten Tomatoes, the score doesn’t supplement criticism; it replaces it altogether. It has acquired the fearsome power of language, supplanting the very words it claims to summarize.

Rotten Tomatoes is bad for many reasons, but its most obvious flaw is that its inputs and outputs are incompatible. Movie reviews, whether they’re short capsules or lengthy treatises, are verbose assessments that aren’t easily reduced to a good-bad binary; sure, some films are wonderful and others are terrible, but many hover around average, and it is the critic’s job to wrestle with their thorny qualities. Yet Rotten Tomatoes obliterates the entire concept of a mixed review, instead foisting upon its members—which, full disclosure, I’ve repeatedly applied (and failed) to join in a flailing effort to improve this site’s traffic—its rigid scheme of “fresh” vs. “rotten.” This flattens complex prose into simple judgments, equating measured evaluations with either raves or pans. (The site’s chief competitor, Metacritic, attempts to evade this trap by assigning a quantitative score to each individual submission, a dubious process that carries its own host of transmutative problems.) The aggregator then mechanically sums up those ironed-out submissions, spits out a percentage, and—voilà!—now you know exactly how well-reviewed a movie is.

Except you don’t. Imagine a movie that received 10 reviews, 9 of which deemed it a masterpiece and 1 of which called it a turd. Now imagine a second movie that also received 10 reviews—9 describing it as “passably diverting” and the tenth labeling it “well-intentioned but ultimately unsuccessful.” Under Rotten Tomatoes’ simplistic rubric, both films receive the identical score of 90%, implying that they were each regarded equivalently by the critical community. (Nomadland and Spider-Man: No Way Home are both sitting at 93%; they’re basically the same movie!)

If you think this sounds silly in the abstract, consider how it works in practice. Two years ago, the site unearthed a negative extant review of Citizen Kane, reducing its score to 99% and prompting dozens of journalists—including one in the paper of record—to report that Orson Welles’ classic now sported a lower rating than Paddington 2 in the supposed competition for “best movie ever.” Before that there was the case of Zootopia, which found readers accusing the two critics (out of 122 in total) who filed “rotten” notices of stupidity and bad faith, and which even led to six-year-old twins contacting one of them and begging him to alter his review to “fresh” so that the film might exhibit a sparkling 100% mark. That’s a cute story which also doubles as a revealing insight: If you are kvetching about a movie’s Rotten Tomatoes score, you are behaving like a child. (Anecdotally, I remain haunted—apparently to the point of having tweeted about it multiple times—by the conversation in which a coworker informed me that, while he mostly liked Arrival, he thought it deserved a score of 95% rather than 99%.)

Again, I understand the site’s theoretical appeal. It’s perfectly reasonable, when you’re deciding whether to watch a movie (or debating between multiple options), to wonder if it was generally liked or disliked by critics. But learning its Rotten Tomatoes score does precious little to help you answer that question. To begin with, the very notion of “critics” is misguided, because we aren’t a hive mind; every critic forms their own opinion, and it’s fallacious to think that hundreds of spiky individual reviews can be smoothed into—as the site dubs it—a uniform “Critics Consensus” (omitting the possessive apostrophe!). Beyond that, the score communicates nothing aside from that aforementioned ironed-out number, deceptively turning subjective, nuanced assessments into cold, unforgiving data. It carries no weight, no color, no meaning.

If you don’t like it, you might say, don’t use it. Sure. But my beef with Rotten Tomatoes goes beyond my personal distaste for its flawed methodology. My real issue is that it’s become a monolith—one that’s poisoned how we talk about movies.

Through its combination of seductive simplicity and commercial might, Rotten Tomatoes has invaded every conceivable corner of modern cinematic discourse. It is everywhere. Before they stopped publishing written analyses altogether (those pesky words!), the number-crunching mavens at Box Office Mojo typically cited a movie’s RT score in their weekly reports, unconsciously implying that this holy metric seamlessly gauges critical enthusiasm. Powerful Twitter accounts like DiscussingFilm (over 910,000 followers) and Film Updates (over 507,000) regularly pronounce “debuts” highlighting a movie’s initial rating as reviews start trickling in, treating a smattering of isolated filings as a newsworthy event. (This becomes even sillier for TV shows, where reviews are often based on a handful of episodes and can’t possibly reflect judgments on an entire season.) And of course there’s the insipid “Certified Fresh!” label, which studios frantically append to their marketing materials in an effort to repackage numerical mush as artistic excellence.

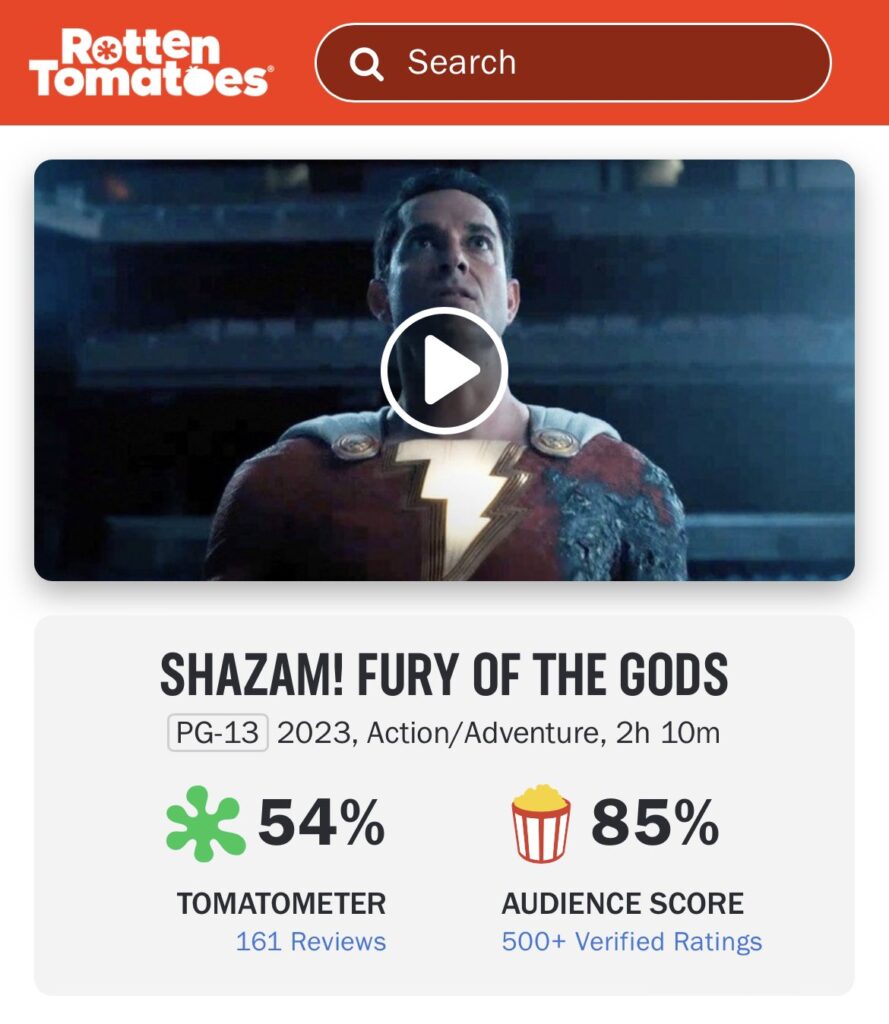

But the problem goes beyond breathless reactions or self-serving puffery. Invariably, arguments about a movie’s worth—whether by fans, critics, or artists—tend to cite its Rotten Tomatoes score as a meaningful data point. The examples are as legion as they are inane: Gawker declaring that Richard Brody is “right about 50% of the time” in part because he praised a film (Amsterdam) that sported a 32% RT rating; clickbait sites ranking the Best Picture nominees by their RT scores; the director of the Shazam sequel bemoaning the discrepancy between its critics’ score and its “audience score.” (Do not get me started on audience scores.)

Not all writers are so myopic; there’s plenty of excellent criticism out there that exists wholly independent of Rotten Tomatoes, and which would remain excellent if the site suddenly disappeared. But discussions of movies routinely turn to the question of how they’re broadly perceived in the critical community (“Were its reviews good or bad?”), and as if through some act of dark magic, Rotten Tomatoes has positioned itself as the default resource for resolving those debates. In so doing, it has warped our minds and perverted our speech, damaging the essential process in which we engage with art.

There’s an alternate universe where Rotten Tomatoes does more good than harm—where it functions akin to IMDb’s “External Reviews” feature and simply compiles work from various critics, without compressing their words into digits. But here in our real, rankings-crazed world, it serves a more nefarious purpose. Rather than operating as a conduit, it is now an endpoint—less criticism’s facilitator than its byproduct. That’s bad for writers and readers alike. There’s rotten, and then there’s trash.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.