It’s 1984, and Air, the new movie by Ben Affleck, wants to make sure you know that. It opens with a blizzard of archival footage and pop-culture clips—the soundtrack quickly shifts from Dire Straits to Violent Femmes—transporting you to the halcyon era of the Ghostbusters, that Apple commercial, and Mr. T. Yet for Affleck, nostalgia is more than a fuzzy feeling; it’s a mode of filmmaking. He fancies himself a throwback—an old-school artisan in the vein of Howard Hawks—which is why his prior feature, the noir flick Live by Night, attempted to echo classic gangster melodramas to the point of embalmment. Air, about Nike’s quest to sign Michael Jordan to an endorsement deal (it was marketed with the subtitle “Courting a Legend”), is a less self-serious picture, and also a more enjoyable one. Watching it is a bit like watching a highlight package of an old sporting event you’ve heard about but never saw live: You can appreciate the talent and the craft on display, even though you already know which team wins at the buzzer.

Speaking of highlights, that introductory blitz isn’t the only time Affleck dips into montage. Though Air takes place exclusively during the year of “Sister Christian” and Beverly Hills Cop—Harold Faltermeyer’s famous synth theme for the latter appears on the soundtrack, even though it wasn’t released until months after the shoe signing (one of many factual liberties cheerfully taken by Alex Convery’s script)—at one point it suddenly travels through time, revealing grainy footage of classic Jordan moments (the hanging game-winner against Cleveland, the lefty layup versus the Lakers, etc.). It’s an understandable impulse, because despite being branded as a sports movie, Air features vanishingly little action or athleticism. In fact, its hero is a paunchy middle-aged white guy who can’t even manage one lap around the track.

That would be Sonny Vaccaro (Affleck bestie Matt Damon), the Nike talent scout whose job is to spot mid-priced NBA draft prospects and match them to the company’s meager basketball budget. Sonny, whom Affleck economically establishes in the opening as both a hoops junkie and a gambling addict—placing a series of bets in Vegas, he asks the teller for the over-under on Kurt Rambis’ point total, then says, “Doesn’t matter, give me the under”—is the kind of coworker everyone respects and nobody likes. He brandishes his superiority like a sword; when a colleague suggests investing in Melvin Turpin, he responds that within four years, Turpin’s career will be flourishing… in Europe.

You remember Melvin Turpin, don’t you? Neither do I. And that’s both the point and the curiosity of Air: It positions itself as a story of reckless heroics—Sonny’s brash ploy is for Nike to assign its entire annual allocation to Jordan, rather than spreading it across multiple young players per usual—yet it orbits around an icon who became one of the greatest and most celebrated athletes of all time. There’s an odd push-pull to the film’s internal logic; yes, Sonny putting all of Nike’s eggs into Jordan’s basket is risky, but that’s partly because the North Carolina stud—and the third overall pick in the 1984 draft—is deemed too expensive for the nation’s third-ranked sneaker outfit. It’s an underdog narrative about an undeniable champion, with David signing Goliath instead of slaying him.

This presents Affleck with a certain degree of difficulty, though one he’s familiar with. In the climax of Argo, he used sharp staging and sly editing to turn an extremely mundane task—waiting in line at the airport—into a sequence of white-knuckle suspense. Here, his challenge is even more daunting, as he tries to imbue the banalities of corporate maneuvering—the boardroom meetings, the strategy sessions, the term sheets—with the thrill of drama and the weight of history.

If he doesn’t entirely succeed, it isn’t a mark against his skill or his judgment. Less exhilarating than absorbing, Air—which would pair well with Hustle, the Adam Sandler vehicle about an NBA scout’s championing of an unknown Spaniard—is about as entertaining as a movie about shoe sales can be. On a macro level, Convery’s screenplay is a bit clunky; in addition to regarding Jordan with hagiographic veneration (recalling the treatment of the Williams sisters in King Richard), its depiction of Sonny as an ingenious maverick feels lazy and reductive. But in terms of rhythm and dialogue, the script sings, overflowing with choice zingers, canny repartee, and delectable morsels of profanity.

Wordplay is the real competition here, and while basketball may be a five-on-five game, Air mostly operates as a series of one-on-one conversations. To execute his vision, Sonny can’t just overpower his foes with the force of his conviction; instead, he needs to calibrate a delicate mix of persistence, persuasion, and ingratiation. Most obviously, he must convince Jordan to sign with Nike, which requires him to wage verbal war with the agent David Falk (Chris Messina), and also to sway Jordan’s mother, Deloris (Viola Davis), why her son shouldn’t flock to the industry’s heavy hitters like Converse or Adidas. (Jordan himself is portrayed by the lanky actor Damian Young, though he’s rarely glimpsed and hardly ever speaks, a smart decision that also reinforces Deloris’ considerable influence.) At the same time, he needs to get Nike to commit to Jordan, meaning he must win over not only head of marketing Rob Strasser (Jason Bateman) but also CEO Phil Knight, whom Affleck conceives as a grouchy and vainglorious figure (check out his purple Porsche), one who could only be played by… Ben Affleck.

The substance of these tête-à-têtes, with their natterings about scoring averages and salary percentages and boards of directors, is not exactly the stuff of legend. (It surely isn’t as gripping as the kidnapping thriller Gone Baby Gone, Affleck’s first and still best work.) But the vigorous pacing and the crisp camerawork—overqualified cinematographer Robert Richardson tosses in a few portentous close-ups, plus one spinning pivot, alongside the precise medium shots—help infuse the proceedings with a semblance of intensity, while the hard-working cast provides pleasure of a different sort.

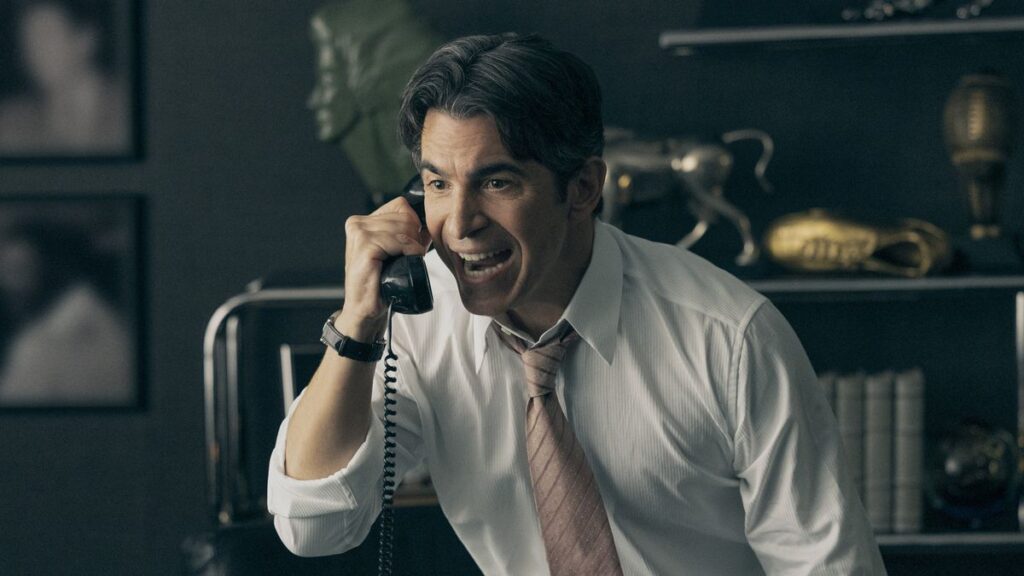

Three different times in Air, someone remarks that “a shoe is just a shoe until somebody steps into it.” Well, a movie is just words on a page until they’re embodied by flesh-and-blood actors. Here, Affleck has assembled a roster of agile thespians who are all capable of blending sincerity with silliness. The film may posture as a study of American greatness and perseverance, but it’s most memorable as an artful medley of jokes and insults. (The backyard moment when Sonny begins to imitate the accent of Adidas’ German executives, only to be swiftly shut down by Deloris, emblematizes the picture’s whip-smart timing.) Bateman and Affleck parry Damon’s boastful resolve with weariness and dyspepsia, respectively, while the ensemble also makes room for warm turns from Chris Tucker (as a glad-handing representative) and Matthew Maher (as a designer in the midst of a midlife crisis). The clear MVP, however, is Messina, who lends Falk a wolfish rapacity only to repeatedly undercut it with childish tantrums; the scenes of Sonny and Falk bickering via landline are electrically funny, and remarkably energetic given that they’re just two dudes talking on the phone.

Air works better as a comedy than a drama; as polished as it is, its gestures toward pathos feel forced. (Certainly they can’t hope to match the raw power of the scene in The Last Dance in which a bereaved Jordan weeps on the locker-room floor.) But just because it doesn’t reach the heights of His Airness doesn’t diminish its fluidity and professionalism, which help it rise above the standard sports-movie chaff. Sonny may be fat and slow, but Air still flashes half-decent hang time.

Grade: B

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.