[EDITOR’S NOTE: In 2003, long before MovieManifesto.com existed, I spent my summer as a 20-year-old college kid writing as many movie reviews as I could. My goal was to compile them all into a website, possibly hosted by Tripod or Geocities, which would surely impress all of the women in my dorm. That never happened—neither the compiling nor the impressing—but the reviews still exist. So, now that I am a wildly successful critic actually have a website, I’ll be publishing those reviews on the respective date of each movie’s 20th anniversary. Against my better judgment, these pieces remain unedited from their original form. I apologize for the quality of the writing; I am less remorseful about the character of my 20-year-old opinions.]

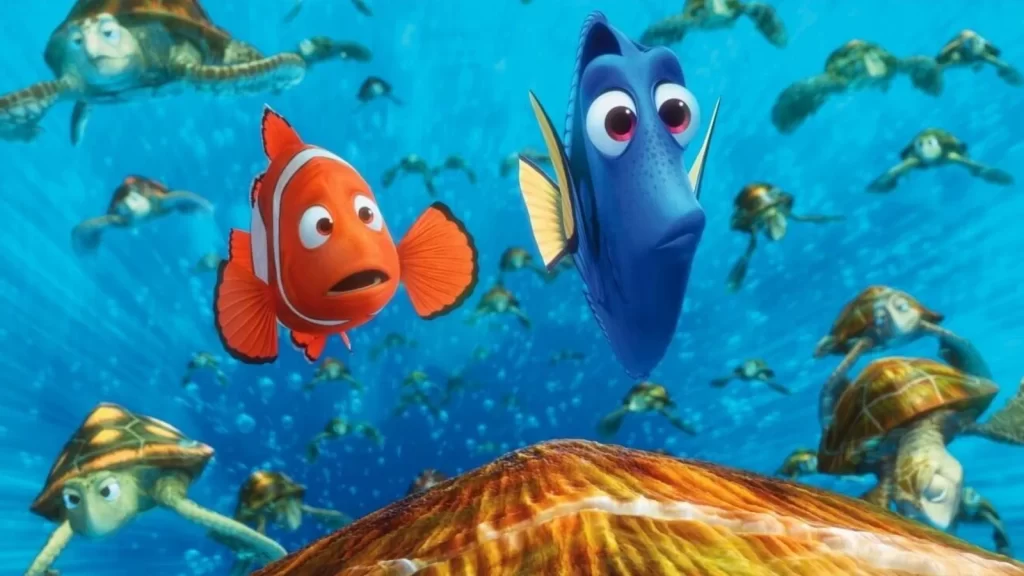

My does this movie have a pulse. This is filmmaking at its most vibrant, an indefatigable romp of breathtaking splendor. Every meticulously constructed frame is teeming with detail, so much so that our eyes despair futilely in a hopeless attempt to digest everything on screen. This visual magnificence is somehow equaled by dialogue that is delightfully droll, and a storyline that is perfect in its simplicity. Adults, check your cynicism at the door; the experience of watching Finding Nemo – the fifth full-length feature from Disney’s Pixar Animation Studios – is one of pure joy.

After a dreadful lull in the latter half of the ‘90s, animation’s stock is once again soaring. Two years ago, the Academy Awards created the category for best animated feature (with DreamWorks’ Shrek narrowly edging out Pixar’s Monsters, Inc.), and the box office has experienced a massive resurgence for animated films as of late. However, this has largely been due not to the typical hand-drawn Disney fare that ruled the early ‘90s (such as Aladdin and The Lion King) but to pictures that are entirely computer-generated, a field in which Pixar is unmistakably paramount. Beginning in 1995 with the smashing success of Toy Story (the first ever feature of its kind), which grossed $191 million domestically, and continuing with A Bug’s Life ($162 million), Toy Story 2 ($245 million), and Monsters, Inc. ($255 million), Pixar has combined technological innovation with imaginative storytelling to return animation to its glory days.

Now, directors Andrew Stanton and Lee Unkrich bring us Finding Nemo, a rollicking adventure that hurls us into the depths of the ocean. After losing his wife and most of his offspring to tragedy (in an opening scene that is startling in its darkness), the clownfish Marlin (Albert Brooks) is paranoid to the extreme. His lone son, Nemo (Alexander Gould), is restless and exasperated with his father’s obsession with safety, and no wonder – Marlin takes “look both ways before you cross the street” to the next level. But on his first day of school, the impetuous Nemo – born with one damaged fin that hampers his ability to swim – takes a detour from his class and heads for the drop-off, an unprotected region of unknown peril. Hearing the news, Marlin dashes to the scene only to see Nemo imprisoned by a scuba diver.

Frantic, Marlin chases after him but collides with Dory (Ellen DeGeneres), a happy-go-lucky fish who happens to suffer from short-term memory loss (if Guy Pearce had a pet in Memento, she was it). Dory, who can read, learns from a fallen pair of sea goggles that Nemo’s captor hails from Sydney, and together she and Marlin set out for the land down under. In the meantime, Nemo finds himself in a dentist’s office, encased in a tank populated by a bizarre assortment of similarly incarcerated fish.

What follows is a marvelous blend of riveting action, ingenious comedy, and high drama, all decked out in one of the most spectacular landscapes ever created. The world of Finding Nemo is luminous and dazzling, with the artist’s full palette of colors consistently on display. Consider the first day of school, in which we hurtle through the neighborhood of the reef with abandon before finally arriving at our destination, at which point the students’ instructor, a stingray (Mr. Ray, of course), glides in lightly and purposefully lands on his pupils. Throughout the sequence, every inch of the frame is used, and every detail subtly nuanced, so that we immediately become immersed in this magical place.

Final Fantasy showed us that we are growing closer (though not quite near) to the stage at which computer-generated and live-action films could be confused for one another, and that hallmark will surely be a worthy one, but the folks at Pixar aren’t concerned with it. They recognize that ever-evolving computer-technology best facilitates the construction of fantasy worlds, those regions previously viewable only via the imagination. It is, we recognize, a treat to be witness to such an invention, especially one crafted so exquisitely. Finding Nemo falls into the elite Mute Category of motion pictures; it would still be enjoyable even if we turned the sound off.

But thank goodness that sound is on, for what characters we meet, and what delectable bits of dialogue they speak. Marlin – who consistently disappoints his fellow fish in that he’s “not very funny for a clownfish” – and Dory stumble into a clan that can only be described as Sharkaholics Anonymous, a twelve-step program with the mantra, “Fish are friends, not food” (this apparently holds true unless the scent of blood is in the air). Then there’s the chivalrous school of minnows that can shape-shift in order to provide directions. We meet a group of seemingly ageless sea turtles, led by Crush (voiced by director Stanton), who comes across as a hybrid of surfer and skydiver with lines like “You’ve got serious thrill issues, dude”. Then there are the predatory birds, both placid pelicans (featuring Geoffrey Rush as Nigel, who has issues with panes of glass) and terrifying seagulls (insatiable in their appetite). And to top it all off, there’s even a whale, both inside and out; if only Pixar had been around in 1940 for Pinocchio.

Nemo’s tank, meanwhile, is a realm to behold in itself, a hyper-aquatic setting yanked right out of The Great Escape. Its inhabitants include Peach (Allison Janney), a kind-hearted starfish; Bloat (Brad Garrett), a blowfish who pays the price for losing his temper; and Gill (Willem Dafoe), a hard-boiled veteran with a handful of failed getaway attempts under his bel-, er, fin. (That these fish have spent so much time in the tank that they are fluent in dentistry jargon and procedure is another of Finding Nemo’s brilliant touches, as is the fact that not all were procured directly from the ocean – one came from the pet store, another off eBay.) Nemo has precious little time with his newfound company, however, as he is scheduled to be transferred into custody of the dentist’s sadistic daughter, Darla, thus forcing another of Gill’s potentially hazardous plans into action.

The actors in Finding Nemo do a worthy job of utilizing their vocal talents to lend their computer-generated characters the proper emotion and feeling. Brooks is particularly effective in bringing his neurotic personality to the obsessive Marlin; likewise, DeGeneres infuses Dory with a bubbly, energetic enthusiasm that is inescapably infectious. Elsewhere, Stanton makes Crush instantly affable with his surfer lingo, and the rest of the supporting cast is seamless in its chemistry (the sharks work particularly well together).

I should hope by now that the myth that animation caters strictly to children has been satisfactorily dispelled. The notion that adults will not be entertained by Finding Nemo is offensive; if anything, older viewers will take more from the film, such as appreciating the music cue for Darla’s entrance (all will agree it is lifted from the proper Hitchcock picture). But this movie functions as far more than a pleasurable diversion. It is an undeniable enchantment, replete with all of the qualities of a major cinematic achievement. Finding Nemo is a treasure.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.