[EDITOR’S NOTE: In 2003, long before MovieManifesto.com existed, I spent my summer as a 20-year-old college kid writing as many movie reviews as I could. My goal was to compile them all into a website, possibly hosted by Tripod or Geocities, which would surely impress all of the women in my dorm. That never happened—neither the compiling nor the impressing—but the reviews still exist. So, now that I am a wildly successful critic actually have a website, I’ll be publishing those reviews on the respective date of each movie’s 20th anniversary. Against my better judgment, these pieces remain unedited from their original form. I apologize for the quality of the writing; I am less remorseful about the character of my 20-year-old opinions.]

The Italian Job showcases the continued emergence of one of cinema’s newest sub-genres: the heist remake. In 1999, John McTiernan delivered The Thomas Crown Affair, a more erotic but less involving film than its 1968 predecessor. Two years ago, Steven Soderbergh’s wildly successful update of Ocean’s Eleven (originally starring Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack in 1960) wowed audiences with its high-profile cast and elaborate set pieces. Now, F. Gary Gray brings us a modernized version of The Italian Job, the 1969 caper featuring Michael Caine.

This is a logical step for Hollywood. Through the advent of superior technology and more mind-blowing special effects, filmmakers can make thievery even more explosive and entertaining while still providing viewers with a cozy, dependable formula. As in Ocean’s Eleven, The Italian Job employs a top-notch cast and sports ample hi-tech eye-candy in an attempt to overpower its audience. However, somewhere along the way, it steps wrong, and what we are left with is a movie that, while mildly entertaining, feels woefully incomplete.

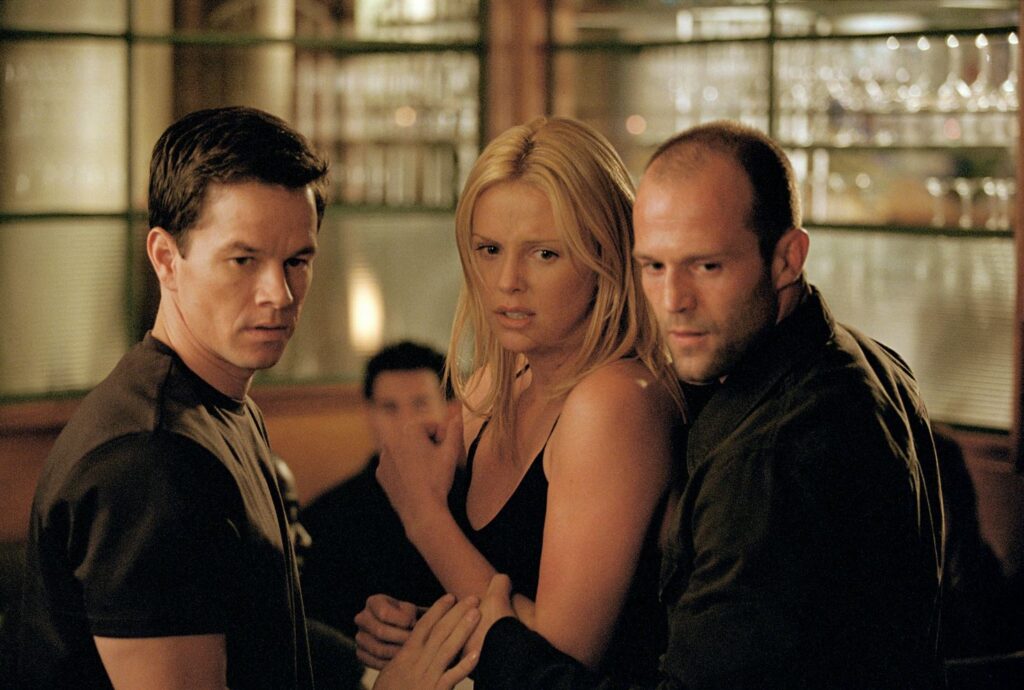

The movie begins with Stella (Charlize Theron) being awoken via a phone call by her father, John (Donald Sutherland). He’s in Venice, about to embark on, well, the Italian Job. Helping him out is a bizarre assortment of established crooks: We have master planner Charlie (Mark Wahlberg), grunt worker Steve (Edward Norton), resident stud Handsome Rob (Jason Statham), computer genius and social dimwit Lyle (Seth Green), and demolition expert Left Ear (Mos Def). This is the kind of dream-team squad only available in the movies, in which every player is unequivocally the best at his particular specialty (to wit, Lyle insists he invented the file-sharing program “Napster” only to have college roommate Shawn Fanning steal the idea while he was, er, napping).

The coveted merchandise is $35 million worth of gold bricks. The plan – a tidy piece of weapon-free work involving a diverting boat chase and an underwater safe-cracking – goes perfectly … or so it first seems. But then Steve decides his share isn’t enough (perhaps because Norton only received third billing). He betrays the crew, shoots John in the heart, and leaves everyone else for dead in the Swiss Alps while escaping with the gold.

We return to the States, where it turns out Stella is a professional safe-cracker herself, only she works with the police. One day, Charlie shows up and proposes that she help his still-livid crew steal the gold back from Steve and avenge her father’s murder. Though Stella initially eschews his offer, she soon relents, and we’re off to Los Angeles, where it’s always sunny and traffic is always terrible, unless you can hack into the city’s automated traffic-light system.

I could tell you the rest, but if you’ve seen the trailer, you already know everything there is to know (the preview reveals not only the film’s major plot developments but also its best one-liners). The biggest problem with The Italian Job (and there are quite a few to choose from) is its predictability. One character says to another, “You just don’t have any imagination”; the same could be said of screenwriters Donna and Wayne Powers. With the exception of the opening scene, we’re always several steps ahead of the action, either because everything is laid out for us in advance (thus removing even the faintest notion of suspense) or because the major sequences are uncomplicated to the point of being banal. The most offensive moment, in which the crew attempts to gain control of an armored truck, is hopelessly foreseeable because the exact same stunt is used in the movie’s opening heist.

It is understandable that the plot of The Italian Job follows the standard, trustworthy pattern of the heist picture, and we thus move gradually from the planning stages to the theft itself, with some comedic banter in between to lighten things up. The flaw here is not the plot but the absence of style. Director Gray has made a film sorely lacking in kinetic energy. He has all the tools at his disposal, including a venerable army of intriguing vehicles (a few astonishing mini-Coopers, armored trucks, motorbikes, and of course a helicopter), but the chase scenes remain languid and uninspiring. Throughout the film, Gray moves listlessly from point A to point B, plodding along, as though adequacy is his goal. The result is an unexciting picture utterly devoid of intensity and anticipation.

That the characters are paper-thin is, while disappointing, to be expected. Far more detrimental, however, is the shoddy dialogue. For a movie like this to work, the characters need to click. Remember the chemistry between George Clooney and Brad Pitt in Ocean’s Eleven, with Clooney asking “How’d she look?” and Pitt responding “She looked good” before he even finished the question? There aren’t any moments like that in The Italian Job. The mood is playful, but it isn’t sharp enough, and most of the talky scenes in the movie feel hackneyed and forced.

In terms of atmosphere, Gray opts for a very light tone, preferring to make his thieves comedic caricatures rather than hard-boiled ex-cons such as in David Mamet’s Heist. It’s probably the smart choice, but the comedy is largely hit-and-miss. There are funny instances, most notably when a jealous Green imagines the dialogue Statham uses while seducing a woman, but those are offset by jokes that are pandered so often that they become irritating (the Napster gag in particular is belabored to death).

The bright spot of The Italian Job is the quality of its acting. Leading the way is Charlize Theron, who again shows that, given a few good scripts, she could quickly work her way to Nicole-Kidman-status – her beauty is matched only by her grace and poise in front of the camera. It’s good to see Edward Norton still diversifying; he had a vaguely similar role in The Score, but it’s essentially his first time as the villain, and he dives into the part with considerable relish (though going a bit more over-the-top couldn’t have hurt). This is comfortable territory for Mark Wahlberg, who basically rehashes his nice-guy characters from Three Kings and The Big Hit – he certainly has the shtick down, but it would be nice to see him branch out a little more. Seth Green and Mos Def provide suitable comic relief, while Jason Statham continues to gain well-deserved American exposure. Donald Sutherland of course dominates his scenes effortlessly.

It’s easy to be overly critical of The Italian Job. In a sense, this is a light, breezy movie that doesn’t try to do too much, and in that context, it meets its expectations. And thanks mainly to the acting, there are a number of successful individual scenes. Sadly, they just don’t add up to much of anything.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.

One of those films that I can remember the day I went to see it surprisingly clearly, but almost nothing of film itself.

I might rewatch it next month as part of a different anniversary project, but “wildly unmemorable” seems appropriate.