It takes less than a minute before we learn that Tomas, the antihero at the center of Ira Sachs’ Passages, is an asshole. He’s directing a movie (also called Passages), and he’s unhappy with how his lead actor is walking down a flight of stairs. Frustrated that the performer keeps swinging his arms, Tomas offers up a piece of criticism that is less than constructive: “Why do you keep fucking up?”

He might be better served asking that question of himself. But then, self-reflection is a foreign practice to the modern narcissist (even if narcissism’s classical etymology is rooted in literal self-reflection). An absorbing portrait of a consummate jerk, Passages is a whirlwind journey of desire and destruction. It has already received notoriety for its sex scenes, which are vigorous and persuasive if not quite pornographic. But it is even more shocking—more raw—as a study of gluttonous appetite and thoughtless cruelty. The callous behavior it displays is recognizably human and also utterly monstrous.

That may not sound like a fun time at the movies. But while Sachs is unapologetic in his honesty, he is not a sadist. His style is at once intimate and detached, capturing the proceedings with a free-floating camera that hovers close to his actors with anthropological inquisitiveness. At times, especially early on, the approach verges on sloppy; you want someone to give him a damn tripod. But the technique grows less irritating as the film progresses, whether because Sachs tamps down his vérité aspirations or because you become too engrossed in the story to notice.

The central contradiction of that story, which Sachs wrote with his usual collaborator Mauricio Zacharias, is that its protagonist is appealing as well as appalling. (It’s not for nothing that one of Sachs’ prior features was called Love Is Strange.) The other two main figures in Tomas’ orbit—Martin (Ben Whishaw), his patient and long-suffering husband, and Agathe (Adèle Exarchopoulos), the schoolteacher whom he has a torrid affair with—are hardly oblivious to his pettiness or his erraticism. (After he first spends the night with Agathe, Tomas returns home and breathlessly proclaims to Martin, “I had sex with a woman!” and the poor bastard just winces before finishing his breakfast.) Yet they also find him strangely charming, as though their logical resistance to his vanity is overpowered by the sheer force of his personality.

This means that the key to Passages is the lead performance of Franz Rogowski, who plays Tomas as a man whose rapacious greed is equaled only by his blinding entitlement. With his slicing lisp and his deep-set eyes, Rogowski is not conventionally attractive, which may explain why his (fantastic) movies with Christian Petzold (Transit, Undine) have placed him in complex quasi-romances that spike their yearning with hesitancy and confusion. But he has screen presence, and he supplies Tomas with a flamboyant confidence that manufactures itself in the form of toxic charisma. You can smell the pheromones oozing out of him.

The plot of Passages isn’t complicated—Tomas cheats on Martin with Agathe, then cheats on Agathe with Martin, and gradually discovers that the rickety love triangle he’s constructed is perilously unstable—and neither are its themes. It’s basically an illustration of the “grass is greener” proverb as applied to bisexual relationships. Initially, Tomas’ fling with Agathe is exciting because it’s new; Sachs stages one of their early encounters, which takes place in an editing suite, with the panting fervor of young love. But passions tend to cool, and Tomas’ inherent capriciousness sends him pinballing between his two conquests (or perhaps victims), even as his swollen ego allows him to concoct a fantasy where they can all coexist in harmony.

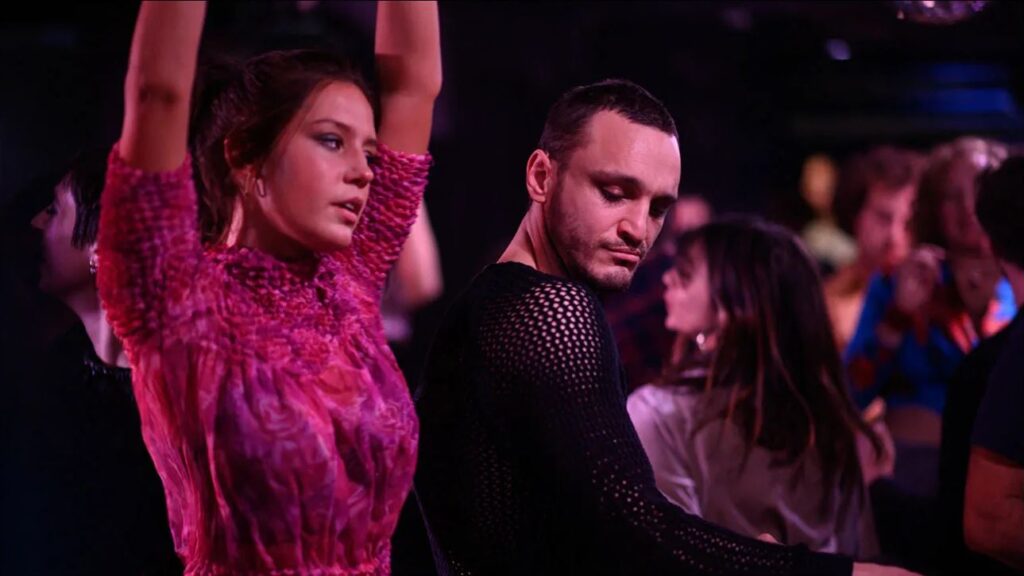

Not exactly provocative stuff. (Certainly it lacks the richness of Blue Is the Warmest Color, another sexually robust picture where Exarchopoulos gets swept up in an illicit romance.) But if Passages’ beauty is skin-deep, it remains undeniably alluring, and not just because of Exarchopoulos’ natural voluptuousness or Rogowski’s fabulous array of sheer crop tops. Despite the simplicity of his narrative, Sachs invests the movie with a feverish, intoxicating intensity. Simple scenes of people sharing meals—an ostensibly pleasant meet-up for drinks at a local bar, a disastrous “meet the parents” luncheon—course with prickly anxiety, while shots of Tomas careening through the Parisian streets on his bicycle throb with hidden menace. There is even an undercurrent of dark humor, whether it’s Tomas triumphantly announcing the positive reaction to his screening at an inopportune time or carelessly climbing into bed with Agathe after having noisily pleasured Martin in the next room.

The nerve of that guy! But despite Rogowski’s repellent magnetism, Passages never treats Tomas as the butt of a joke, instead regarding him with curiosity and sincerity. Yet it also recognizes that he’s an emotional black hole, which is why its most heartbreaking scene—a quiet tête-à-tête between Martin and Agathe at a diner—features Tomas nowhere to be found. Only in his absence can they finally understand one another, and gain the clarity he himself will never receive. His roving eyes may constantly search out new objects of desire, yet he never acquires the courage to look in the mirror.

Grade: B

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.