Just what kind of genius is Hercule Poirot? Six years ago, in his remake of Murder on the Orient Express, Kenneth Branagh reimagined Agatha Christie’s famous detective as a man obsessed with balance; his gift for crime-solving derived from his preternatural ability to recognize when clues and alibis didn’t line up. In his two ensuing movies—first the forgettable Death on the Nile, now the somewhat-improved Haunting in Venice—Branagh seems to have abandoned this conceit, instead depicting his super-sleuth as a quasi-scientist who unravels mysteries through the rigorous application of “order and method.” He isn’t some sort of deductive wizard; he just pays attention.

This doesn’t make Poirot an especially interesting character, but it does function as a handy metaphor for Branagh’s own filmmaking. The traps inherent in the murder-mystery picture—the isolated location, the assemblage of suspects, the cheap twists and red herrings, the destination overshadowing the journey—are difficult to evade. This time out, Branagh doesn’t so much avoid them as skillfully blunt their impact. His version of “order and method” is to deploy familiar cinematic tools in order to bring energy and flair to a production whose narrative bones are dusty and creaky. A Haunting in Venice doesn’t exactly revive this moldy skeleton, but it does clothe it in alluring imagery and spooky atmosphere.

This is partly a matter of geography. Where Branagh’s prior installments placed Poirot on mobile vessels, Haunting takes place almost entirely within a grand mansion whose spiked gates and dark hallways quickly manufacture a cloud of claustrophobia. The trope of suspicious characters locked in a house with a fresh corpse is classical for a reason, and here the Gothic production design (by John Paul Kelly) imbues the palazzo with palpable menace, from its checkered floors to its looming statues to its cavernous fireplaces. The string-heavy score from Hildur Guðnadóttir only amplifies the sense of overwrought dread. That the movie’s events unfold over the course of a dark and stormy night is almost overkill.

Those events, as it happens, are rather pro forma. Poirot opens Haunting in a state of abstinence and isolation; having grown disenchanted with world affairs (we’re now in post-war Italy), he has withdrawn from public life and refuses to work as a detective, relying on a manservant (Riccardo Scamarcio, from John Wick 2) to shield him from the pleading riffraff. (One of the film’s more amusing images is the long line of potential clients loitering outside Poirot’s home, all desperate to retain his services.) But we didn’t buy a ticket to watch Hercule Poirot not solve a murder, and soon he’s acquiescing to Ariadne (Tina Fey), an old friend and novelist who—in a premise that weirdly recalls Woody Allen’s Magic in the Moonlight—implores him to help her expose a purported psychic (Michelle Yeoh) as a charlatan. This requires him to attend a séance, where he crowds alongside a number of curious characters: a grieving opera singer (Kelly Reilly), a committed housekeeper (Camille Cottin), a beleaguered doctor (Jamie Dornan), the doctor’s precocious preteen boy (Jude Hill), a pompous gold-digger (Kyle Allen), and the medium’s shifty and sulky assistants (Emma Laird and Ali Khan).

Laid out like that, this group of slightly off-kilter people looks an awful lot like a list of murder suspects. And sure enough, following an oddly bewitching sequence that finds Poirot bobbing for apples, somebody turns into some dead body. Good thing the man who previously described himself as “the greatest detective in the world” is around to sift through the clues and identify the culprit.

You were expecting something else? For a genre that putatively traffics in deception and surprise, the murder mystery is fundamentally a creature of formula. The potential killers will be interviewed and unsettled. Simmering grudges and ulterior motives will emerge. Seemingly trivial details from the first act—a borrowed mask, a serving of tea, a flavor of honey—will prove significant in the third. And in the climax, our intrepid gumshoe will arrange all of the disparate puzzle pieces into an elegant and satisfying tapestry.

A Haunting in Venice doesn’t presume to deviate from this blueprint—Branagh lacks the ingenuity of Rian Johnson, whose one-two punch of Knives Out and Glass Onion remains the modern gold standard—instead executing it with a competence that is neither enervating nor electrifying. The movie’s final reveal, for example, is hardly explosive, but it also doesn’t cheat, and its simplicity affords it a measure of integrity. Certain plot points—the confounding circumstances of a stabbing, the identity of an unknown blackmailer—are intriguing, even if their resolution is ultimately beside the point.

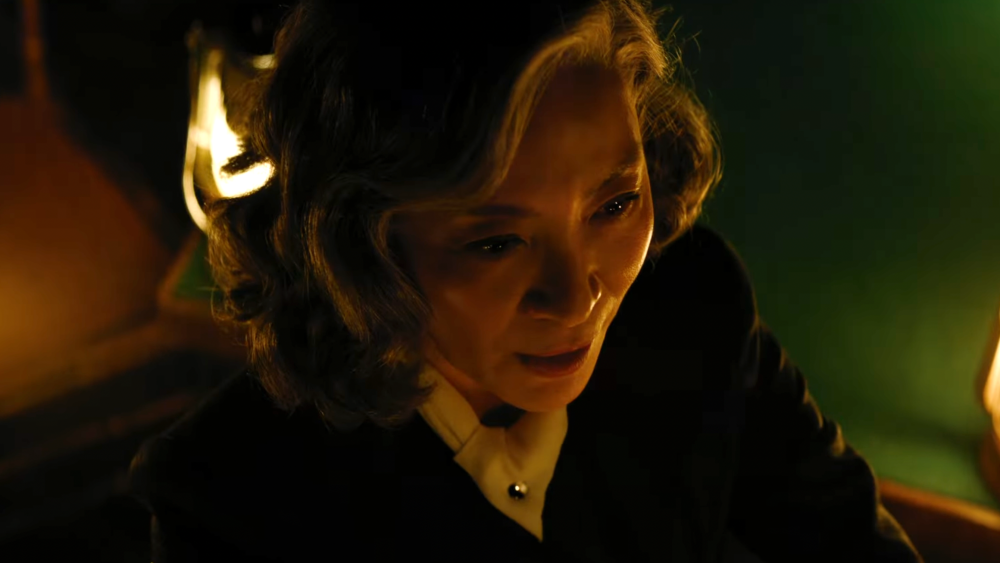

What makes A Haunting in Venice more entertaining than its immediate predecessors is the level of visual panache Branagh brings to its staging. As a director, he is often accused of being staid, but here he is proudly extravagant, wielding his camera with playful showmanship. The sheer variety of tricks on display—canted angles, sweeping pivots, tinted colors, even upside-down tilts—is eye-catching, and any charges of undue flamboyance miss the point; the visibility is purposeful, lending cinematic verve to an enterprise that is musty and literary.

This aesthetic grandeur is crucial, as it helps to distract you from the movie’s thematic shortcomings. The ostensible emotional hook of Michael Green’s screenplay (adapting Christie’s Hallowe’en Party) is Poirot’s crisis of faith; he is a man adrift, and his strange experiences in the (haunted?) palazzo are meant to both rattle his worldview and restore his self-confidence. It’s an evolutionary journey that makes theoretical sense—early on, Poirot attacks the notion of the psychic’s alleged ghost-summoning with an anger that plays as defensive, only to gradually question the veracity of his own assumptions—but while Branagh supplies an amiable performance (his hammy accent and hearty mustache both return, each slightly less pronounced than before), he can’t turn Poirot into a three-dimensional figure. Worse, the film envisions his resistance to the idea of the supernatural as a fortress that slowly softens and cracks; in doing so, it betrays both the character’s intellectual rigidity and Christie’s pitiless lucidity.

And while Branagh is plainly having fun behind the camera, he might have encouraged his cast to do the same in front of it. Instead, few of the actors here capitalize on the hokey material; most of them simply blend into the scenery, aside from Fey, who seems decidedly out of place. The happy exception is Hill, who follows up his lead role in Branagh’s Belfast by showcasing a crisp intelligence that portends a future in pictures beyond cute-kid preciousness.

“They called it small beer,” Ariadne kvetches of her latest novel’s critical notices. The same assessment might apply to A Haunting in Venice, which is generally diverting yet cheerfully insignificant. But it is at least a movie, with a robust visual identity and a pronounced level of filmmaking style. Hercule Poirot is on the case, and cinema ain’t dying on his watch.

Grade: B-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.