It was a new iteration of a familiar conversation. Speaking with a coworker about my prior evening, I explained that I’d watched a movie (shocker), and that I’d procured it in the form of a Blu-ray disc from Netflix’s DVD-by-mail service. He gawped in amazement: “Netflix still sends DVDs??”

Sadly, not for much longer. At the end of this month, after 21 years of glorious pony-express shipping, Netflix will finally close its brick-and-mortar (disc-and-mailer?) operation and focus exclusively on online streaming. In a way, it’s hard to believe it lasted this long. The company foresaw our digital-dominant present as early as 2007, when it introduced a novel plan to “deliver movies and TV shows directly to users’ PCs” (imagine that!). But it really ushered in the demise of its postal venture in February 2013, when it entered the original-programming space and introduced a little series called House of Cards, which was immediately available to binge in its entirety. (Who wants to watch TV this way, I scoffed.) In retrospect, it’s something of a miracle that Netflix’s DVD arm survived for a full decade from that point, even if the breadth of its selection continually shrank as the corporation poured money and sweat into the streaming wars.

Things were not always smooth. There were queue snafus, cracked discs, and botched mailings. (I still recall, with a measure of first-world bitterness, gearing up to watch George A. Romero’s Day of the Dead in 2009, only to discover that my envelope instead contained the DVD for the 2008 remake starring Nick Cannon and Mena Suvari.) There were also head-scratching business decisions and, as time wore on, frustrating conflations between movies and “content.” There was even outright stupidity, as in 2011 when CEO Reed Hastings inexplicably decided that Netflix’s mail operation would split into an independent service called Qwikster, only to hastily reverse course following mass outcry from customers.

Still, for all its glitches, “DVD Netflix” remained an invaluable product for cinephiles who seek to burrow into various nooks and crannies of the medium’s rich history (especially once actual video stores shuttered). Sure, plenty of mainstream movies quickly arrive on a streaming service these days, but that’s far less true for independent titles or foreign films, many of which I never could have seen absent Netflix’s help. (And I say this as someone who lives in a relatively large city where most limited releases screen in theaters; for those in more remote locations, the red envelope could function as its own makeshift art house.) That’s to say nothing of classics; despite the recent emergence of the Criterion Channel, DVD Netflix was often the only option for anyone looking to watch a particular movie made before 1980. And in an era where corporations are constantly vanishing their intellectual property for tax write-offs or otherwise tarnishing the movie-watching experience—just two weeks ago, the dipshits at Max hypothesized about interrupting consumers’ viewing with breaking news alerts for CNN+—there is something sacred about the tangible permanence of a physical disc that can’t be corrupted with split screens or cropped aspect ratios. (A dozen years ago, I wrote this piece hyping 10 different TV shows available to watch on Netflix’s streaming service; today, exactly two of them are still on Netflix.)

Speaking of permanence, DVD Netflix couldn’t last forever—not when streaming culture has prioritized algorithmic recommendations over user-driven curation (why manage a queue when the app can select a title for you?), and certainly not once the internet became the primary means of home viewing. But it had a long and fruitful run, and—to shift things in a narcissistic direction—so did I. According to the company’s internal housekeeping statistics, I “rented” a total of 1,308 discs from Netflix over my 17 years as a subscriber. Depending on your perspective, that number is either appallingly high or disappointingly low. But movies are about quality rather than quantity, and I’m less interested in calculating how much I consumed than in examining how my use of the service evolved over time.

And so, with apologies for the navel-gazing, allow me to take a brief tour of my personal history with DVD Netflix, selecting one meaningful title that I rented in each of my years as a customer—beginning with my very first disc:

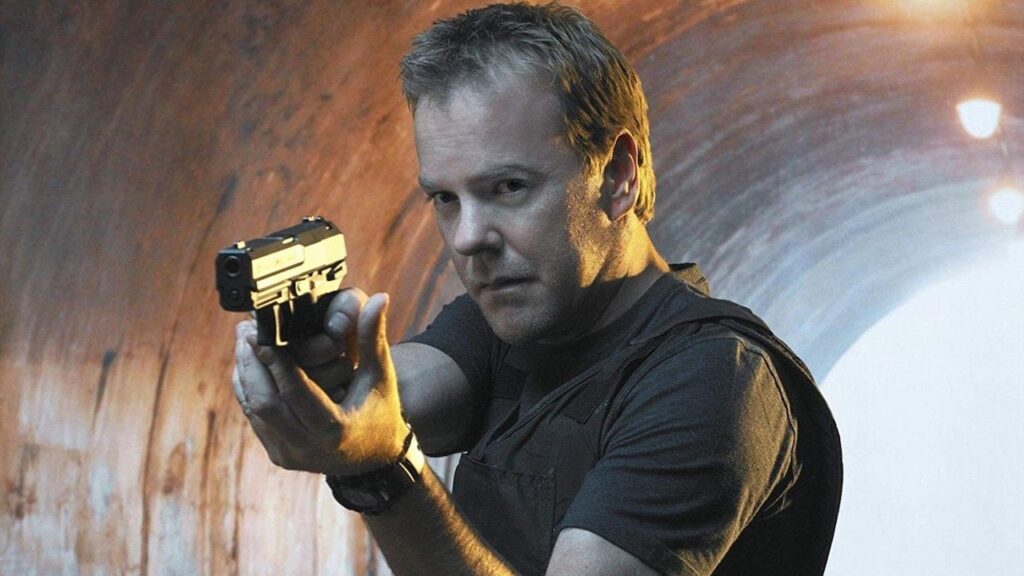

2006: 24 (Seasons 1-4). I’m not sure why I waited until 2006 before finally pulling the trigger on a Netflix subscription (probably a lack of personal funds), but I remember precisely when and why I took the plunge: I was depressed that my favorite basketball team had lost in March Madness, and I wanted to cheer myself up. I’d never watched 24 during its broadcast run, and given that coworkers were constantly praising it, it became the logical pick for my first addition to my fabled queue. It was a satisfying choice that also proved strangely prophetic, given that the show’s cliffhanger-heavy approach signaled television’s shift toward the binge model. Of course, I devoured the series as fast as possible, routinely watching all four episodes contained on each disc in a single evening in my rush to catch up with the then-airing Season 5. (It wasn’t until nine years later, when I gained a better appreciation for the value of the episode as a unit of storytelling, that I imposed my current policy—never watch multiple hours of the same show in the same night; naturally, this is the exact opposite of the style of viewing Netflix encourages, as the company still prides itself on dumping out entire seasons of TV all at once.)

2007: Strangers on a Train. I didn’t much appreciate this Alfred Hitchcock classic when I first watched it, apparently giving it only two stars(!) back when I was still using Netflix’s pointless rating system, which has since devolved into an even more pointless thumbs-up/thumbs-down rubric. (In theory these ratings were designed to feed into the service’s recommendation engine, which I entirely ignored.) I should probably watch it again, but guess what? It currently isn’t available on any streaming service for free. (My moral code distinguishes between streaming and “video on demand,” which requires payment for each individual rental and which defeats the purpose of paying subscription fees to all of these damn companies.) If only someone would invent a company that sends you DVDs in the mail in exchange for a monthly fee…

2008: Mad Men (Season 1). You need to remember that AMC’s breakout hit wasn’t always a phenomenon; at the dawn of its second season in July 2008, it was more regarded as a niche critical hit than a water-cooler sensation (at least not in my anecdotal experience). You also need to remember that “catching up” on prior seasons of television wasn’t always easy; yes, some channels had their own “on demand” analogues, but they were notoriously unreliable and didn’t always include every episode. Thankfully, I’d heard enough vague buzz surrounding Mad Men to add these three discs to my queue in advance of Season 2. From that point forward, I watched every new episode when it aired on cable, though I sometimes needed to wait until the day after because Comcast didn’t broadcast AMC in HD until 2011, yet it did offer HD via its on-demand channel. Man, the aughts were wild.

2009: Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Seasons 1-4). It seems absurd to say now, given that I typically watch over 100 TV shows each year, but I didn’t consume much television as a teenager in the ’90s. As a result, I missed this WB treasure until a decade later, at which point it joined Mad Men on my all-time Mount Rushmore of TV shows. (The other two are the final series listed in this piece and the predecessor to my favorite program of last year.) Buffy, of course, aired for seven total seasons, and I watched the final three through Netflix’s streaming service rather than its discs. But the series is also a cautionary tale for studio meddling; a “remastered” HD version in 2014 was reportedly disastrous for how it re-cropped the squarish image in order to fill widescreen TVs. It’s a crucial reminder that the internet is always transitory, whereas DVDs are forever.

2010: The House of the Devil. One of the many reasons I prefer watching movies in theaters whenever possible is that the experience imprints more strongly on my memory. My home-viewing environment is pretty good, and I do my best to minimize distractions (dark room, phone on silent, etc.), but the cold truth is that a movie is less likely to stick in my hippocampus when I watch it on TV. So it’s always gratifying when specific titles do stay with me, despite the suboptimal viewing conditions. I don’t pretend to recall everything about The House of the Devil, Ti West’s silky ’80s-horror homage. But I will always remember the captivating sequence where Jocelin Donahue boogies around an isolated mansion while jamming out to The Fixx on her Walkman, and I will never forget the scene where a young actress by the name of Greta Gerwig gets… well, see for yourself; the film is currently streaming on AMC+, if you’re fortunate enough to subscribe to that service. (See what I mean about the value of DVD Netflix as a one-stop shop?)

2011: Enter the Void. Not all memories are good. It’s unusual for me to actively despise a movie; selection bias means that I rarely seek out pictures which are widely regarded as bad. But even though his reputation as a provocateur compels me to keep checking out his work, I’ve never liked a Gaspar Noé film, and I absolutely hated Enter the Void, a 143-minute odyssey of death and torment and masturbatory showmanship. With a movie this dreadful, the at-home experience creates a magnifying effect; in the theater, you can invisibly commiserate with fellow customers (and remind yourself that you paid good money for your ticket), but alone on the couch, the mere act of watching feels pointless. One way that I attempt to mitigate this sensation is my philosophical refusal never to turn off a movie once I start it; as a result, I finished Enter the Void out of principle, even if I wished I’d never started it.

2012: Mysteries of Lisbon. I generally ignore Movie Length Discourse; long movies can be good, short movies can be bad, and the graphical scatterplot of runtime and quality looks like a blast of buckshot. (I am eagerly anticipating heading to the theater next month to see Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, which reportedly runs 210 minutes.) Still, I’m not sure if I could have absorbed this enchanting, wildly ambitious generational drama from Raúl Ruiz in a single sitting, given that it transpires for over four-and-a-half hours. Netflix apparently anticipated this issue (or was bound by the technology of the time), splitting up the picture onto two different discs and mailing them separately. It was one of the rare instances where the comforts of home viewing—the ability to schedule your own intermission or pause for a bathroom break—outweighed the drawbacks.

2013: Before Sunrise/Before Sunset. The recent rise (and perhaps ongoing fall) of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and similar franchises has occasionally turned movie-viewing into homework, requiring audiences to study up on prior installments before turning out for the latest episode. In terms of narrative and aesthetic priorities, Richard Linklater’s Before films can’t be any further removed from superhero flicks. But they still form a unified trilogy, and the release of Before Midnight provided me with the happy excuse to revisit Celine and Jesse’s first two days together—a process that DVD Netflix easily facilitated.

2014: Proxy. On weekends, I tend to watch most movies with my dad, whether in the theater or at home. But for discs I receive during the week, I typically watch them myself before bringing them to my parents’ place and telling him to view it on his own time. The key is the implicit responsibility. Recommend a movie to someone, and they’ll invariably express polite interest but never actually watch it. (If you doubt the veracity of this, ask yourself how many times in the past year you chose to watch a movie directly following someone else’s endorsement.) But when you hand them a physical disc, you transfer along with it a sense of obligation: Crap, I need to do something with this. I’ve induced my father into watching hundreds of movies this way that he likely never would have seen otherwise. (He could always have just mailed discs back without watching them, but he’s not an asshole like that.) Zack Parker’s Proxy sticks out in my mind because it’s such a gonzo piece of filmmaking (the title refers to Munchausen Syndrome by proxy, which was later explored in Sharp Objects); after he watched it, my dad emailed me stating that it had kept him awake until 2:00 a.m. and sarcastically asking, “Where do you hear about these cheerful movies?” Happy to be of service.

2015: Mad Max: Fury Road. I don’t rewatch many movies. My rationale is simple: Life is short, and I’m already not going to be able to consume everything I want to before I die, so it’s hard to justify spending multiple hours revisiting something I’ve already seen. But now and then I’ll feel compelled to do just that, especially where my reaction doesn’t align with the consensus. Mad Max: Fury Road wasn’t just the A.V. Club’s pick for best movie of 2015; it was the site’s favorite film of the decade. My first viewing inspired this largely positively, somewhat reserved review, so I turned to DVD Netflix to see what I’d missed. (The ultimate verdict: It’s a wildly impressive movie that is still critically lacking in terms of plot and character, I was right, everyone else was wrong, #sorrynotsorry)

2016: The Tribe. One challenge of being an amateur critic is trying to watch as many acclaimed movies as you can when those movies barely seem to exist. The Tribe never played in more than nine theaters across the country, and I can understand why: It’s a deeply challenging film, following a school for deaf teenage delinquents without subtitling their sign language (the better to place you in their headspace of confusion and alienation). It’s utterly unique, but it’s also one of many strange and thrilling pictures I never would’ve seen absent DVD Netflix’s once-extensive catalog. In that regard, the service was weirdly heroic. Hear hear.

2017: Lady Macbeth. Florence Pugh is one of the best actors alive, and I’ve been raving about her for years, from Midsommar to Fighting with My Family to Little Women to Black Widow to Oppenheimer. (She’s even excellent in Don’t Worry Darling.) I saw all of those movies in theaters, but I first discovered Pugh’s greatness in Lady Macbeth, a spiky period piece that reorients our understanding of the “bored housewife” picture. I don’t remember why I added it to my Netflix queue, but I’ve never forgotten it or its leading lady since.

2018: Professor Marston and the Wonder Women. And here we have a tragic quirk of timing. I neglected to catch this knotty love triangle—which tells the true-ish story of the creator of the Wonder Woman comic (played by Luke Evans) and his throuple with two women (Bella Heathcote and a riveting Rebecca Hall)—while it played in theaters in October 2017, so as with countless other titles, I resolved to catch up with it via Netflix. But the company didn’t ship me the disc until February 15, 2018—the exact same day I published my list of the 10 best movies of 2017 (a list which, as it happens, includes Lady Macbeth). I’ll always wonder if I would’ve found room for it on that list, but I’ll never doubt that it’s a fantastic film, sexy and heady and brimming with feeling.

2019: Dragged Across Concrete. I don’t pretend to be hugely principled in terms of boycotts, but paying money to watch Mel Gibson in modern times feels rather distasteful. That made DVD Netflix the ideal mechanism to catch up with this S. Craig Zahler thriller, a bruising cops-and-robbers yarn that combines vulgar themes with unimpeachable craft. If you saw it in theaters, I don’t judge you, I just don’t want to sit next to you.

2020: Ammonite. Remember the COVID-19 pandemic? That totally defunct disease that definitely isn’t still surging across the country? Among its other consequences, it put a bit of a damper on my moviegoing habits in 2020, when streaming shifted from ancillary option to exclusive mode of viewing. But those red envelopes still paid off, never more so than when they allowed me to watch this majestic romance, starring Kate Winslet and Saoirse Ronan, before I’d filed my year-end list. From a cinephilic perspective, Ammonite represented a strange turning point in the pandemic, as it was the last great new release which COVID robbed me of seeing in theaters. In that sense, I hope I never see its like again, though the flaring chemistry between Winslet and Ronan was already inimitable.

2021: Blow-Up. And here we have the flip side—the so-called “return to normalcy.” Vaccinated and masked, I cautiously returned to theaters in 2021, at which point I reorganized my Netflix queue and prioritized older titles I’d never seen. You hardly need me to describe Antonioni’s Blow-Up to you, but watching the Blu-ray from home in August 2021, I wasn’t just catching up with a classic; I was luxuriating in a restored sense of order. This, I remembered, is what the service was for—the opportunity to supplement, to fill in gaps, to pluck particular selections at random. Good thing it was never going away.

2022: Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn. Turns out streamers don’t just botch old TV shows. The majority of this Romanian satire is academic and dialogue-driven, exploring the fallout after a high school teacher learns that an ostensibly private sex tape she made with her husband has gone viral. But it opens with the making of that sex tape itself, in all its sweaty unsimulated glory. Yet when Hulu aired the movie, it censored the prologue—and in the process substantiated the film’s themes of societal prudishness and high-minded morality. Thankfully, the DVD that I received from Netflix presented the movie in its original version, making it uncut in more ways than one.

2023: The Child. In the end, DVD Netflix was about making it easier for people to watch good movies. The Child, the second film by the Dardenne Brothers to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes, is a very good movie, but you won’t find it on any streaming service (again, as distinct from VOD). Maybe it’s a foolish thought experiment, but I like to imagine a burgeoning cinephile resolving to watch all of the Palme d’Or winners, and formulating a plan of attack on how to acquire them; what better service could there be to accomplish such a task than DVD Netflix? For more than two decades, it was the most reliable option for lovers of cinema to track down hard-to-find films: obscure indies, treasured classics, forgotten studio ventures. It never had everything, but it cumulatively contained more than anything else. The service may be dead; its red envelopes will live on forever.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.