Among the most insufferable criticisms lobbed toward Martin Scorsese—not the most insufferable; here will be the first and last time this review mentions the words “Marvel Cinematic Universe”—is that his only good movies are the ones about gangsters. Taste may be subjective, but aside from ignoring the vast majority of the director’s fertile filmography, this grievance neglects the organizational rot that runs through so many of his pictures. Sure, it’s obvious that the suits in The Wolf of Wall Street are just thugs with brokerage licenses, but even when Scorsese isn’t explicitly dealing with lawbreakers, he is routinely wandering halls of power and exploring systems of iniquity. The snobbish aristocrats of The Age of Innocence, the monopolistic bureaucrats of The Aviator, the dogmatic zealots of The Last Temptation of Christ—they are all veritable hoodlums, seeking to impose their chosen brand of moral order upon the world, intolerant of individual resistance.

Killers of the Flower Moon, Scorsese’s latest movie and one of his best, is even less tangential to the gangster genre than his films about musicians or comedians or pool sharks. It doesn’t nominally feature mobsters who say “fuggedaboutit,” but its tale of criminality and corruption occupies the same thematic territory as that of Mean Streets or Goodfellas. Yet where those classics exhibited joy in depicting the mechanics of their antiheroes’ frenzied avarice, Flower Moon finds Scorsese operating in a more mournful register. It isn’t that age has mellowed him—in some ways, this is among the angriest pictures he’s ever made—so much as it’s nudged his focal point. The methods of vice are no longer the primary attraction; what matters now are the consequences.

A similar sense of doleful remorse animated his prior movie, The Irishman, and the commonalities don’t end there. Every new Scorsese joint is an event, but over the past decade he has devoted himself to making weighty epics whose lengthy runtimes are commensurate with their sociological breadth. If Wolf of Wall Street basked in the inherent rapaciousness of capitalism, his follow-ups grappled with no less than the mystery of God (Silence) and the inexorable march of mortality (The Irishman). Now, he has turned his penetrating eye to the evils of colonialism, considering how the American frontier—through means legal, extralegal, and immoral—operated to homogenize its people, and to barter dollars for souls.

Based on a book by David Grann (Scorsese wrote the screenplay with Eric Roth), Flower Moon opens with a scene of funereal gloom: Elders of the Osage tribe, ground down by the persistent encroachment of white invaders, lament the loss of their lands and the erosion of their culture. But then: oil! As title cards inform us of the clan’s peerless prosperity—dubbed “the Chosen People,” they were the richest per-capita sect in the world—jubilant natives dance amid geysers of black liquid, accompanied by Robbie Robertson’s period-specific score. The remainder of this very long, very ambitious, very good movie examines the illusory nature of this wealth, and how it left the Osage vulnerable to manipulation and brutality.

Our prodigal point of entry into this fraught landscape is Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), a World War I veteran who returns home to Oklahoma with the twin goals of getting rich and getting laid. He locates the chance to satisfy both in the person of Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone), an Osage beauty who’s ticketed to inherit lucrative “headrights” but whose funds are nevertheless “restricted.” (What does that mean? Don’t worry about it, at least not right now.) Seizing an opportunity to serve as Mollie’s chauffeur, Ernest quickly charms her with his boyish good looks and rascally demeanor. Squint from a certain angle, and the first hour of Flower Moon looks a bit like a romantic comedy, observing Ernest and Mollie’s courtship with playfulness and warmth.

“He’s not that smart,” Mollie says to a relative, “but he’s handsome.” This description is typically only half-true of characters played by DiCaprio, whose collaborations with Scorsese have eagerly exploited the actor’s electrifying intelligence. Ernest isn’t exactly a numbskull, but he’s a tool rather than an engineer—early on, we see him reading a history book by moving his finger along with the words, akin to a toddler—and DiCaprio, redirecting the energy from his brain to his chin and lower lip, lends him a guilelessness that’s both sweet and sad. He’s a patsy, which makes him the ideal instrument of the Osage’s destruction.

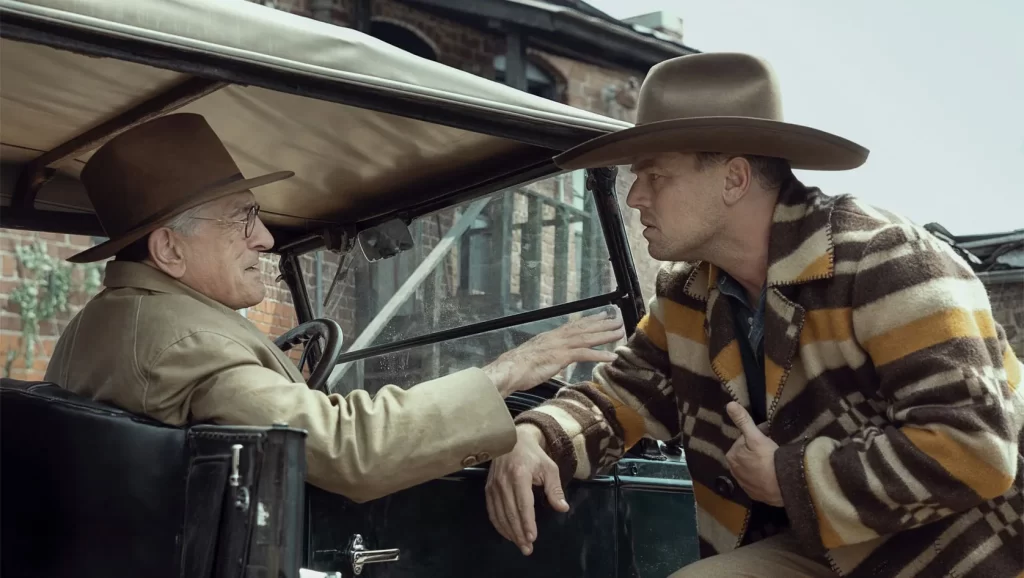

The architect of that reckoning is William Hale (a terrifying Robert De Niro), Ernest’s uncle and the region’s smiling tyrant. “You can call me King,” he suggests to Ernest upon the latter’s arrival, and the label is more than just a term of familial affection. Hale, we soon learn, is deploying a plan to systematically break the Osage’s stranglehold on oil ownership—a scheme that recalls Patrick McGoohan’s vulgar line from Braveheart: “If we can’t get them out, we’ll breed them out.” (Note the enthusiasm with which someone says to Ernest of his new girlfriend, “She’s full-blood!”) Ernest’s seduction of Mollie is just one of many prongs Hale wields in his gradual, relentless attack.

The specific contours of those prongs are not immediately apparent, which is less a signal of Scorsese’s tactical withholding than a sign of his indifference. As a storyteller, he is more concerned with sweep than clarity, meaning he tends to hurtle past key scenes and plot points, only to circle around to them later. It’s a bold approach with uneven returns. Unlike The Irishman, whose profligate runtime included stretches of slackness and confusion, Flower Moon is more methodical and purposeful, consistently conveying its overarching ideas even if the details remain fuzzy. (An early sequence in which Mollie recounts a number of Osage deaths, each of which inspired “no investigation,” sets the stage for Hale’s stratagem of cleansing.) It is also somewhat imprecise, forcing viewers to perform the labor of puzzling out timelines and identities without affording them a corresponding payoff.

Yet even if certain events in Flower Moon are inscrutable, the power of its overall vision is undeniable. What’s curious is that Scorsese, long an aggressive and flamboyant stylist, here has subdued his filmmaking technique in the service of his story. The movie’s look and feel is impressive and enveloping—the camera, operated by Rodrigo Prieto (working with Scorsese for the fourth consecutive time), often glides steadily through interiors—but it is not especially emphatic. This strikes me not as a lack of directorial verve but as a thoughtful and intentional modulation. The drama of the piece—an epic coursing with lucidity, sorrow, and rage—is sufficiently potent without artificial embellishment.

Or maybe I was just too busy admiring the actors. DiCaprio’s magnetism is at this point axiomatic, but his star wattage seems to have ignited a renewed fire in De Niro, who delivers arguably his most invigorating performance since Heat. Hale’s dominion over the community is so unquestioned, he doesn’t even bother to flaunt his influence, instead exhibiting it through calm, chilling relaxation; the scene in which an FBI agent (Jesse Plemons, always welcome) interrogates Hale while he’s receiving a shave pulses with unspoken menace. Gladstone, meanwhile, weaponizes a different sort of silence, allowing waves of melancholy and recognition to wash over her face as she underlines Mollie’s haunting predicament. This goes beyond the debilitating illness that consigns her to her bed (and, annoyingly, minimizes her screen time); it also applies to her crippling combination of omniscience and helplessness. Mollie sees everything yet can do nothing.

For all its historical grandeur, Flower Moon centers these three characters, casting them as the players in a domestic melodrama of passion and greed. “I just love money,” Ernest says at one point. “I love it almost as much as I love my wife.” The potential dissipation of the adverb in that sentence becomes the engine of the movie’s suspense and the source of its most devastating tragedy. A late reunion in a sun-kissed field glows with tenderness (not to mention evokes one of my favorite shots in Pride & Prejudice), only to be upended by a simple dinner-table conversation that vaporizes a character’s romanticism into ash.

Of course, Scorsese is too restless and expansive to concentrate solely on his leads. Instead, he broadens the picture’s scope, making room for colorful side figures and thorny subplots. Some of these are blackly comic—such as a throwaway scene in which a flunky (Louis Cancelmi) asks his lawyer about murdering his wife and kids for their money, then clarifies that he only plans to take such action if it’s legal—while others, most notably those involving the dreadful fates of Mollie’s family (complete with a symbolic owl), are pointed and somber. Scorsese, leveraging the film’s much-publicized (and altogether absorbing) 206-minute runtime, attempts to thread them into a damning tapestry of malfeasance, venality, and loss.

Whether he succeeds is debatable, and also kind of beside the point; Killers of the Flower Moon emphatically amounts to more than the sum of its parts. As its final act morphs briefly into a tense courtroom drama (including cameos from a sharp John Lithgow and a bloviating Brendan Fraser), the movie itself delivers its own furious, fiery verdict—indicting not just Ernest, Hale, and many other individuals (including Ernest’s brother, played by a very fine Scott Shepherd), but an entire ecosystem of callous imperialism. The title of Grann’s book (which I’ve not read) vividly conjures the image of innocence yielding to barbarity; on screen, Scorsese lends that image shape and force, personalizing a campaign of slaughter and imbuing it with pitiful humanity.

That he has channeled such an atrocity into a piece of boisterous entertainment is an apparent contradiction—one which he explodes in the movie’s final scene, an act of brilliant ingenuity whose particular bravura should remain unspoiled. Suffice it to say that Scorsese is simultaneously defending his chosen art form and exposing its tendency to compress the sprawl of history into didactic, digestible packages. This is not so much a gesture of self-critique as an acknowledgement of cinema’s peculiar and invaluable place in our own cultural landscape. We can’t escape our past; the best we can do is turn it into movies.

Grade: A-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.