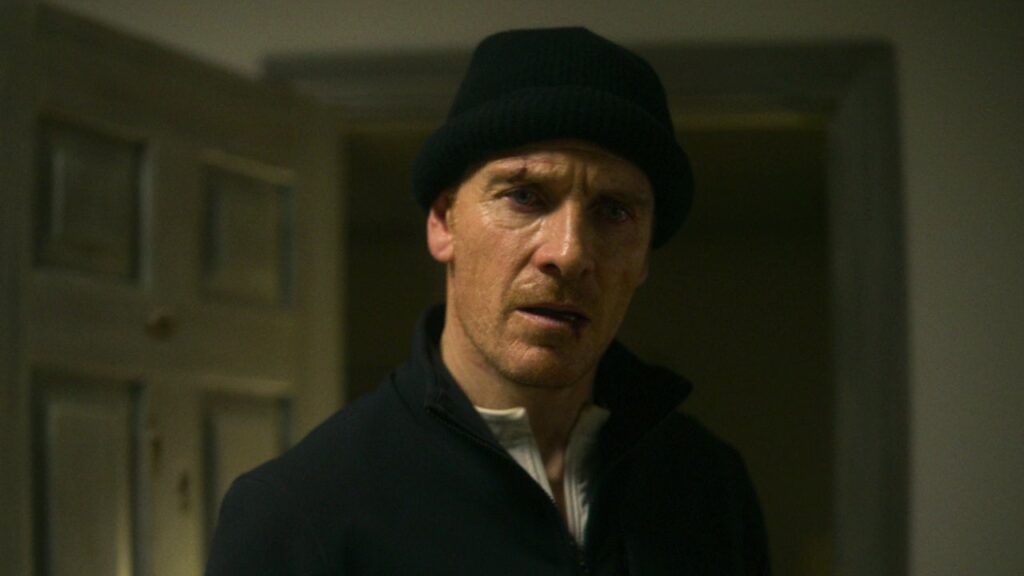

Critics are invariably tempted to draw parallels between artists and their subjects, but with The Killer, David Fincher almost makes it too easy. Here is a movie about a man who practices his craft with fanatical exactitude, who exhibits unwavering patience, who abides by a ruthless set of codes and rituals. Remind you of anyone? The only apparent difference between Fincher and his titular character, an assassin for hire played with sleek magnetism by Michael Fassbender, is that the latter aims a gun instead of a camera.

OK, maybe not the only difference. To begin with, for all of his apparent experience and expertise, it’s unclear whether The Killer—who’s unnamed, so let’s call him TK—is especially good at his job. When we first meet him in Paris (after a brisk and absorbing title sequence, a Fincher specialty), he’s sitting in a vacant WeWork loft (WetWork?), calmly educating us—in the nonstop, blackly comic voiceover that will accompany the entire film—on the physical challenges of doing nothing. Even ignoring the picture’s title, TK’s accoutrements—a high-powered arsenal (including a sniper rifle), a spiffy set of binoculars, a wristwatch tracking his biometrics (pro tip: never pull the trigger unless your pulse is under 60)—convey that his vocation is murder. Yet despite his thorough surveillance and his ascetic mantras (e.g., forbid empathy), he botches the hit. It will not be the last mistake he makes, though it is the catalyzing one; the remainder of this fleet, exhilarating movie chronicles the fallout of TK’s error and the pileup of bodies it produces.

It’s ill-advised to focus on the plot of The Killer, because there’s barely any plot to focus on. The screenplay, by Se7en writer Andrew Kevin Walker (adapting Alexis Nolent and Luc Jacamon’s graphic novel), is structured like the cross between a videogame adventure and a John Wick flick. (There is even a scene of the protagonist retrieving a cache of weapons from a floor safe, though where Keanu Reeves evinced world-weary resolve, Fassbender instead offers detached lethality.) Returning home to the Dominican Republic to find his girlfriend having been assaulted as retribution for his professional failure, TK embarks on a tour of vengeance, methodically tracking down his handlers and superiors and dispatching them with extreme prejudice. The episodes of his spree are categorized into brief, Seinfeld-ian chapter titles—The Lawyer, The Expert, The Brute—each of which retains its own flavor and geography. (Speaking of Seinfeld, the many aliases that TK deploys are all names of famous TV characters, suggesting either an impish sense of humor or a flagrant disregard for clandestine protocols.)

The Killer’s broad strokes may seem rudimentary, but its organizational simplicity frees Fincher up to devote himself to matters of technique, which is where he excels. The images in this movie are crisp and clean, but where it really distinguishes itself is its music and sound. Armed with a classic iPod to go with his pistol, TK is a fan of the Smiths, a seemingly ridiculous penchant that strangely supplies the picture with a sense of sonic continuity. Yet Fincher is doing more than just flattering fans of ’80s post-punk. Once TK starts cranking “Well I Wonder” during the opening sequence, the soundtrack floods with Morrissey’s baritone during exterior shots, only for it to periodically recede whenever our antihero muses about cleanup procedures or bullet trajectories; it’s sharp editing that instantly establishes TK as both part of the outside world and isolated from it. As for the doomy musical score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (working with Fincher for the sixth straight time), it couldn’t be further removed from the Smiths’ dreamy melodies, but its relentless drone is equally immersive.

Speaking of immersion, The Killer plants itself firmly inside TK’s brain—in addition to his practical pointers on stealth and camouflage, we hear his ruminations on philosophy and population growth—even as it refuses to soften his edges. This doesn’t mean the character remains static; rather, we watch as his rigid principles (“weakness is vulnerability”) collide against the elastic realities of his vendetta. Essentially, he’s an inhumane killing machine whose glimmers of humanity are only revealed through complication and failure. Yet The Killer isn’t a redemption narrative; Fincher is far too unsentimental and process-oriented to translate TK’s lapses in professional judgment into his acquisition of a soul. Instead, the movie observes TK’s minute shifts in mood with clinical curiosity. Midway through, he again laundry-lists his various credos while silently recognizing that he’s betrayed all of them, then recalls his single most important tenet and wryly asks himself, “How’s ‘don’t give a fuck’ going?”

The precise tenor of that line reading—playful, regretful, self-aware—exemplifies the cool calculation of Fassbender’s performance. It’s a challenging role because TK is by design a figure of minimal depth; most of his interactions with other people are brief and functional (and typically result in their death), meaning we only really understand him from his constant narration. Yet his wiry physicality is convincing, and works in tandem with the voiceover; when he inadvertently kills a victim six minutes before the intended time, the look of irritation on his face blends perfectly with his internal expletive. Strip away its explosive violence, and The Killer could function as a dark comedy of compulsive mania, and while some of TK’s remarks might seem a bit cute on the page—a reference to Wordle, a quip about Storage Wars, “What would John Wilkes Booth do?”—Fassbender delivers them with just the right touch of knowing absurdity.

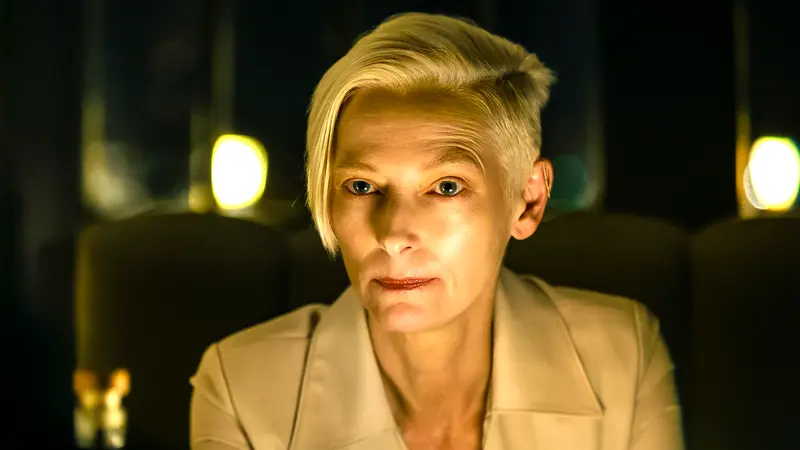

Of course, that explosive violence has long been Fincher’s stock in trade. Genre vehicles like The Killer tend to flag in energy as they proceed, but Fincher paces this one expertly, allowing it to accumulate robust momentum without gorging on carnage. That’s why he waits until the second half to unveil the movie’s signature set piece: a rough-and-tumble brawl between TK and a roided-out Florida maniac (Sala Baker) that bursts with cacophonous mayhem—splintered walls, shattered televisions, hurled utensils, vengeful pit bulls—yet which never sacrifices visual clarity. That Fincher follows such an invigorating melee with a far different kind of duel, in which the great Tilda Swinton regales TK with a vulgar parable as she sips artisanal whiskey, is a testament to his discipline as well as his filmmaking skill.

The Killer is more entertaining in the moment than in retrospect, when its thinness of character and theme grow more apparent. Judged against the impossibly high standards of Fincher’s filmography, it’s possible to perceive it as a minor work; certainly it lacks the scathing wit of The Social Network, the twisty complexity of Gone Girl, the provocative satire of Fight Club. (It is less ambitious but more assured than his prior effort, the gorgeous but overstuffed Mank.) But if its pleasures are surface-level, those surfaces are polished to an almighty gleam.

So just how similar are David Fincher and The Killer? Maybe not at all, despite their shared obsessive rigor. After all, Fassbender’s hit man opens the movie shooting the wrong target, setting the stage for The Killer’s electrifying medley of blades and bullets and blood, along with the forceful reminder that its director simply cannot miss.

Grade: B+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.