It takes roughly 15 minutes before Priscilla announces itself as a Sofia Coppola movie. Priscilla Beaulieu (Cailee Spaeny), a meek 14-year-old American girl living on an army base in Germany, has just shared her first kiss with Elvis Presley (Euphoria’s Jacob Elordi), possibly the most popular musical artist on the planet. As she glides down her school hallway—oblivious to her surroundings, deep in the swoon of adolescent love—“Crimson and Clover” flares to life on the soundtrack. The year is 1959, nearly a decade before Tommy James yearned for a girl he hardly knew to come walking over, but Coppola has never let anachronisms get in the way of emotions. Priscilla is hopelessly smitten, and Priscilla represents Coppola’s attempt to capture both the purity of her rapture and the agony of its inevitable deflation.

Strangely, this blissful sequence is something of an outlier—a fleeting moment of canny cinematic imagination in a picture that is broadly functional and orthodox. It’s weird, because conceptually speaking, Priscilla’s pairing of artist and subject seems ideal. Even setting aside her filial connections to Hollywood royalty, Coppola has long been fascinated by celebrity, having considered it through the various lenses of middle-aged ennui (Lost in Translation), historical opulence (Marie Antoinette), and vicarious obsession (The Bling Ring). Yet where those movies all hummed with vivacious technique and energetic style, Priscilla is oddly conventional. Apart from some sharp music cues and a few arresting images (such as a woman walking down a corridor bathed in red light), it feels like anyone could have made it.

Credit Priscilla for what it isn’t: an Elvis movie. Coppola based her screenplay on Priscilla Presley’s memoir, Elvis and Me (co-written by Sandra Harmon), and her change of title is astute; the King is a secondary character here, even if his erratic behavior buffets our titular hero in all directions. (The soundtrack is entirely devoid of Presley’s music.) It is of course tempting to compare Priscilla with Elvis, Baz Luhrmann’s swaggering Oscar-nominated epic starring a hip-swiveling Austin Butler, but the two films are barely even related; Colonel Tom Parker, flamboyantly embodied by Tom Hanks for Luhrmann, is never glimpsed on screen here, relegated instead to Elvis’ repeated murmurings about “the colonel.” (Presley’s father, Vernon (Tim Post), fulfills the role of career taskmaster.)

Freed from the genre obligations of making a dutiful biopic, Coppola instead attempts to focus on Priscilla’s swirl of contradictory feelings: desire and regret, elation and frustration, triumph and loss. You might say that her approach is a less more conversation, a little less action. And in fact, Priscilla proves most persuasive as a nuanced study of a particular form of domestic abuse. That Elvis is a full 10 years older than Priscilla isn’t lost on anyone (least of all her concerned parents), but his initial courtship of her appears to be the opposite of predatory; he asks her father for permission, he ensures she’s home by curfew, and he resists her sexual advances. He presents as a perfectly wholesome southern gentleman who just happens to be the biggest pop star in the world.

There’s a “but” coming, but not the type you expect. Aside from an angrily hurled chair (which is immediately followed by an apology), Elvis’ mistreatment of Priscilla once she travels to Memphis isn’t physical in nature. It instead lies in the way he wields his wealth and stature in order to possess her. When she floats the possibility of getting a part-time job, he quickly nixes the idea: “It’s me or a career, baby.” Later, he instructs her on which dresses to buy (“It’s not your color, baby”) and how to apply her makeup, leading to the jet-black bouffant that becomes her signature look and the movie’s symbol of invisible oppression. Even Elvis’ persistent withholding of sex morphs from chivalrous to hypocritical, once you factor in his other relationships. By the time his stepmother chides Priscilla for playing with a puppy in the front yard (in view of the ogling public), it’s clear that for her, Graceland is a gilded cage.

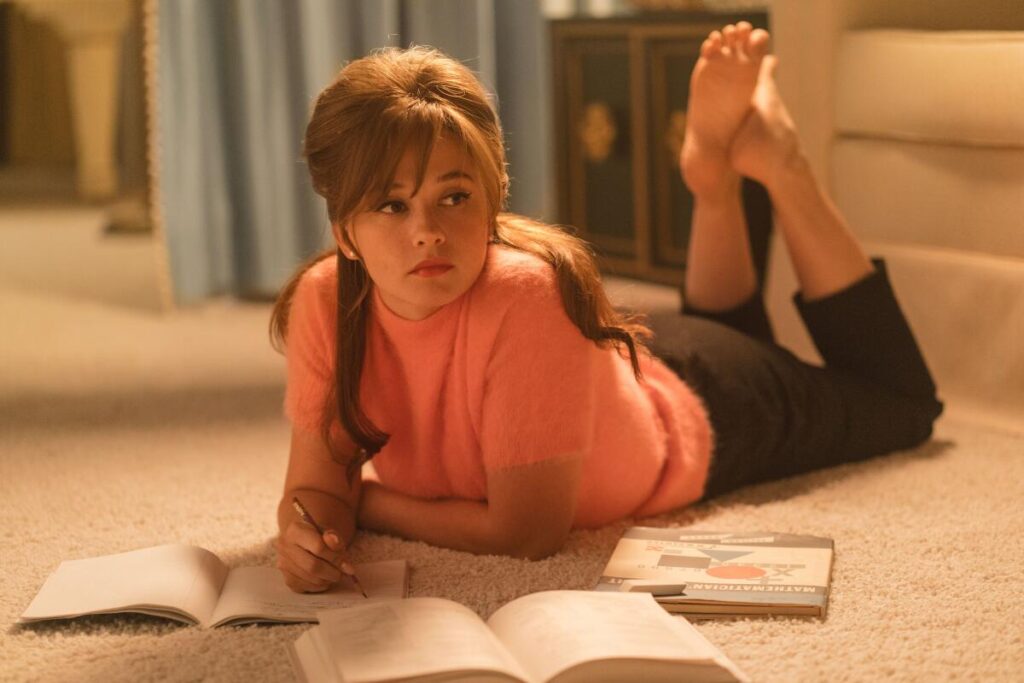

It’s a troubling relationship, and the actors lend texture to its twisted shape. They’re nearly the same age, but Elordi is a giant and Spaeny is a sprite (the makeup department makes her look tremulously young in the early scenes), and his towering over her emblematizes the characters’ imbalance of power. Aside from his (perfectly credible) accent, Elordi doesn’t try to do too much, allowing Elvis’ domineering temperament to flow from his body as a form of effortless entitlement. He leaves the heavy emotional lifting to Spaeny (previously best known to me from her television work on Devs and Mare of Easttown), who internalizes Priscilla’s heartache and conveys her numbing pain, as when she enters labor and, before heading to the maternity ward, immediately dons her fake eyelashes.

That’s another insightful piece of visual communication, but the movie is weirdly short on such instances. Priscilla is an intriguing heroine; she isn’t very bright—even before we see her cheat on a math test, she exclaims “21!” at a blackjack table only for Elvis to point out, “Baby, that’s 22”—but her wants and needs are genuine, and Spaeny renders her sympathetic without making her pitiful. Yet her on-screen journey carries limited heft, suggesting that Coppola’s inventive instincts were cabined by the sad contours of her subject’s biography. Priscilla isn’t exactly a tragedy—there is a decent amount of (ahem) euphoria on display, along with a noble attempt to reclaim Priscilla’s narrative and invest it with feminist agency—but the story it tells is largely predictable and unpleasant.

Of course, the same might have been said about recreating the life and (off-screen) death of Marie Antoinette, but Coppola’s nervy telling of France’s final pre-revolution queen evaded its hagiographic traps through a combination of glamorous filmmaking and delicate empathy. Priscilla sports little of the former, and while it features plenty of the latter, it struggles to convey meaningful ideas about the paralytic nature of celebrity. It paints a convincing portrait of an unhappy woman imprisoned in a restrictive marriage, yet it never quite conjures Graceland as its own, inimitable heartbreak hotel.

Grade: B-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.