Writing is a task infected with misery and failure: an endless cycle of staring at a blank screen, deleting reams of gibberish, and questioning your life choices. (Am I speaking hypothetically? Reader, I am not.) So it was with a mixture of envy and disbelief that I watched Thelonious Ellison (Jeffrey Wright), better known for obvious reasons as Monk, sit at his desk and confidently compose an entire novel in what appeared to be a single night. What’s his next trick, building Rome?

Not that Monk is an especially successful artist. The flailing hero of American Fiction, Monk is a mythological scholar whose fearsome intellect has failed to translate into financial security or critical renown. (When he appears at a book panel, he scratches a missing vowel onto the placard that misspelled his name.) His latest text, a meticulous analysis of Aeschylus’ The Persians, hasn’t attracted the slightest nibble from publishers, given that it’s miles removed from the zeitgeist. “They want a Black book,” explains his agent, Arthur (John Ortiz). Monk’s frustrated response—“I’m Black, and it’s my book”—betrays not only his stubbornness, but his woeful ignorance of consumer demand.

The nature of that demand is the thematic center of American Fiction, the debut feature from Cord Jefferson, who gleefully lampoons the contemporary readership in ways both trenchant and tedious. In Jefferson’s telling, the modern white book-buying audience is a virtue-signalling lot with an appetite for a particular flavor of socially conscious art—a hunger that can be sated only via ostensibly inflammatory literature which flatters their sense of cultural progressivism without causing them any actual discomfort. Armed with this rudimentary understanding of prevailing sensibilities, Monk resolves to exploit the market for exploitation, retreating to his aforementioned desk and scrawling out a phony memoir called My Pafology. (The moment when he wincingly replaces the “th” with a single “f” is one of the movie’s cleverer touches.)

Crucial to the ideology of American Fiction is our recognition that My Pafology, which Monk ascribes with the pen name Stagg R. Leigh, is a very bad book—a degrading and simplistic work that traffics in cheap thrills and crude stereotypes. Jefferson, whose prior TV writing credits include The Good Place and Watchmen, wisely spends little time embellishing this fact; what we learn of the actual text derives from a single, canny scene that shows Monk in literal conversation with his fictional characters (played by Okieriete Onaodowan and Keith David), who snarl at each other in exaggerated dialect about gangs and drugs before periodically turning to Monk and asking him without affect, “What do I say now?” My Pafology is tacky hackwork, and Monk hate-writes it not in a desperate effort to cater to lowbrow tastes but as a vengeful act of antagonism, hoping to rattle the industry’s higher-ups and expose the intellectual vacuity of their crass opportunism. Are they not entertained?

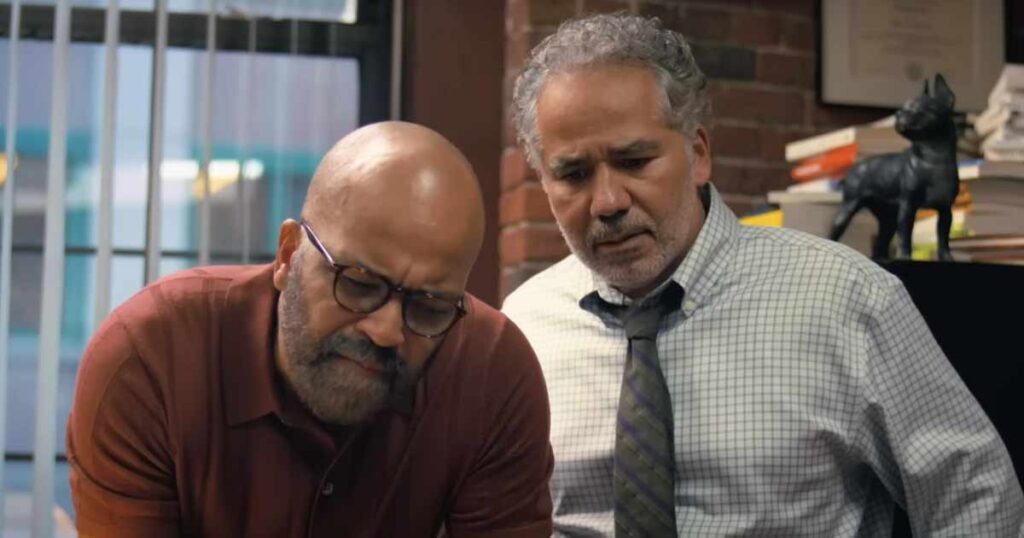

Turns out, they very much are. American Fiction envisions a world where the clueless literary establishment—primarily embodied by a credulous publisher (Miriam Shor) and her simpering assistant (Michael Cyril Creighton)—fawns over My Pafology, transforming it into a runaway bestseller as well as a critical smash. In terms of satire, this development isn’t all that explosive or (ahem) novel; the depiction of critics as an undiscerning bunch of clout-chasers is as familiar as it is tiresome. (Am I taking it personally? Reader, I am.) But it does present some opportunities for laughter, which Jefferson and his cast mine with alacrity and wit; simple scenes of Monk sitting in Arthur’s office, attempting to adopt a posture of uncouth thuggery, are very funny in their dissonance. (When Monk politely identifies himself over the phone by saying, “This is he,” Arthur shoots him a pained grimace, prompting him to add, “Motherfucker.”)

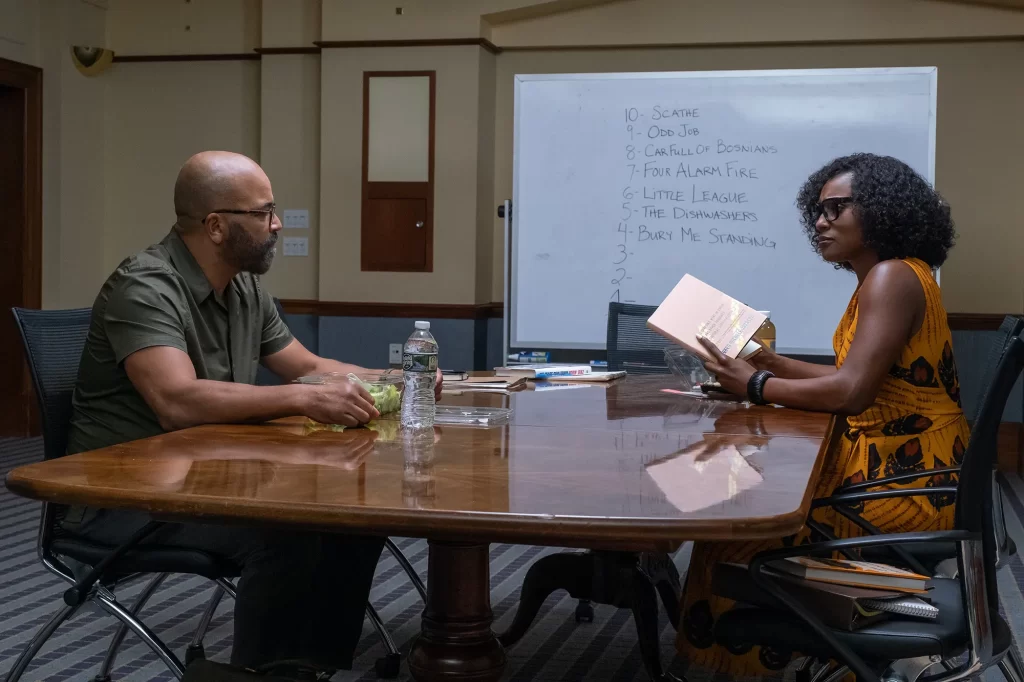

Jefferson, who also wrote the screenplay (adapting a novel by Percival Everett), presumably wants American Fiction to function as a piece of genuine agitprop as well as a crowd-pleasing comedy—a film that forces you to reassess your relationship with and appreciation of Black art. It’s an ambitious goal, but the execution is uneven. Monk’s drastic decision to fabricate My Pafology is inspired in part by Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), a fellow writer who has just achieved monumental acclaim with her ludicrously titled book, We’s Lives in Da Ghetto. Circumstances conspire for Monk and Sintara to work together, and it’s a nice touch when he discovers that she isn’t a talentless hack but is instead a judicious and insightful thinker. Yet a late scene in which they debate the merits of their respective works is stiff and staid, functioning less as a revelatory set piece than a didactic seminar. What’s more, the white characters in their orbit are painful caricatures, an understandable choice that nevertheless feels reductive rather than reciprocal.

The upshot is that American Fiction’s satire manages to be provocative without being persuasive. Fortunately, Jefferson isn’t focused exclusively on his message; he has also crafted a family melodrama that is by turns funny, complicated, and moving. Banished from his Los Angeles university for cultural insensitivity—in a playful irony, his ownership of a racial epithet wounds some of his white students—Monk returns home to Boston, where he discovers a different sort of mess. His mother, Agnes (Leslie Uggams), is wrestling with the early stages of dementia, a burden that until now has fallen on his sister, Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross), a doctor whose work at an abortion clinic drains her of the energy required to deal with a decaying parent. Also eventually present is their brother, Cliff (Sterling K. Brown), a recent divorcé who is embracing his newfound freedom with a hedonism that might give the characters in My Pafology pause.

The collision of these high-strung personalities—a clash that mingles regret, resentment, and loyalty—rests somewhat uneasily alongside Jefferson’s more putatively stimulating ideas. But on their own terms, the scenes between Monk and his siblings are wonderful. (Less enchanting is the romance he undertakes with a neighbor played by Erika Alexander, who seems to have no interior life beyond serving as a compass for Monk’s moral failings.) Ross and Brown both have limited screen time, but they still create fully realized characters who brim with their own dashed hopes and swirling desires; it’s easy to imagine Lisa and Cliff each headlining their own movie. And while Wright’s sly, intuitive performance is most purely enjoyable during the sequences where he tries to manufacture Monk’s felonious swagger, he is also deeply empathetic in the moments opposite his family, lending grace and texture to the material even as his director prefers to operate with brute force.

Which isn’t necessarily uncalled for. After all, as I write this, my Twitter feed is bombarding me with ads from a conservative think tank (if there is such a thing) pushing the hashtag #DemolishDEI and railing against “anti-white racism.” No doubt Monk would have plenty to say about such loaded rhetoric, given that at one point he’s recruited to judge a literary competition whose history is regrettably monochrome. (He responds that he’s honored to have been selected “out of all the Black writers you could go to for fear of being called racist.”) As a dialectical argument, American Fiction isn’t wholly cohesive, but it at least grapples with the intersection of art and race, and it does so with a bracing combination of earnestness and humor. You may not buy everything it’s selling. But reader, you will be entertained.

Grade: B

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.