Last year, Netflix released David Fincher’s The Killer, a fit between director and subject matter that was so hand-in-glove perfect, it practically felt like a self-portrait. Now the streaming giant is “distributing” (to your TV set, if not to your local theater) Richard Linklater’s Hit Man—a less obvious match. Linklater’s career is sufficiently long (his first feature came in 1990) that he can’t be pigeonholed into a single genre, but his best-known works—Dazed and Confused, the Before trilogy, Boyhood—are talky, leisurely dramedies that contemplate the passage of time with relaxed, unforced intimacy. He’s an ambler, not a sprinter. This is the guy to make a movie about an undercover faux assassin?

Turns out, the pairing—like Linklater’s cozy, fluid dialogue—is natural and smooth. That’s partly because Gary Johnson, the New Orleans philosophy professor whose real-life exploits entrapping solicitors of murder were previously chronicled by Skip Hollandsworth in a Texas Monthly article, is less a killer than a bullshitter; he outfoxes his quarry rather than overpowering them. But it’s also because Linklater has wielded his gift for capturing the idiosyncrasies of human connection—the freewheeling conversations, the swirling emotions, the physical attraction—and retrofitted it into a crime-adjacent thriller that’s more concerned with pleasure than violence. The result is a movie that’s consistently enjoyable and even a little suspenseful.

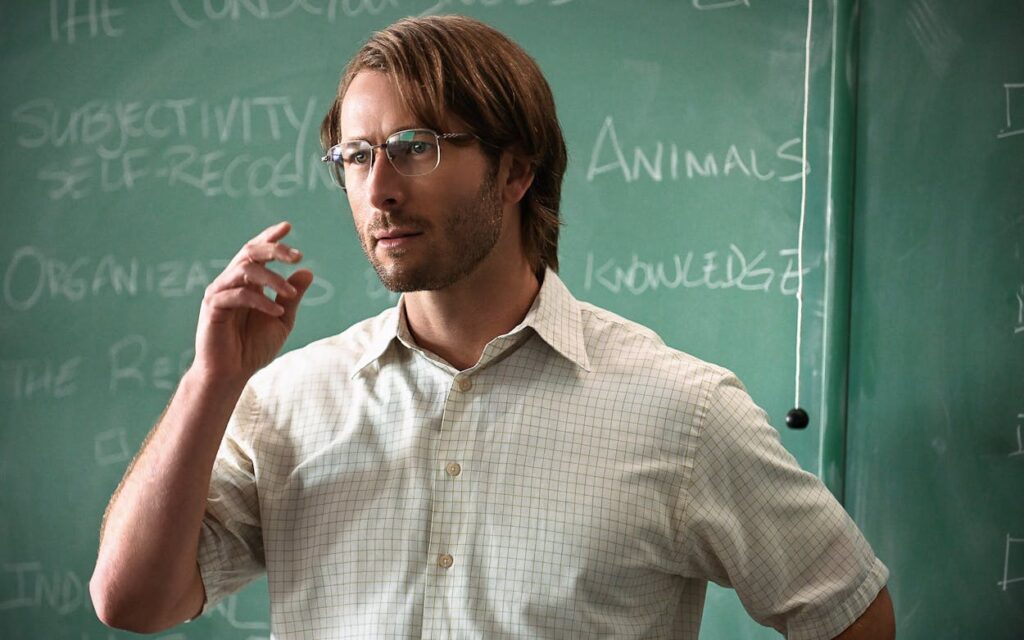

When we first meet Gary, he doesn’t look like much; this is something of a miracle performed by the film’s makeup department given that he’s played by Glen Powell, the slab of beefcake who recently torched the screen alongside Sydney Sweeney in Anyone But You. With his stringy hair and rimless glasses, Gary is the quintessential nebbish, whether he’s lecturing to yawning students about self-determination or working his sideline with the NOPD, where he wires surveillance equipment for sting operations. A pure man-in-the-van bookworm (his two cats are named Id and Ego), Gary is thrust into face-to-face duty when his superior, Jasper (Austin Amelio, who worked with Powell on Linklater’s Everybody Wants Some), is placed on suspension. (The screenplay, which Linklater and Powell wrote together, instantly brands Jasper as disreputable when he blames the reprimand on “cancel culture bullshit.”)

The opening stretch of Hit Man, in which Gary repeatedly impersonates a for-hire assassin in order to coerce unsuspecting “clients” into purchasing his services on tape, is its least engaging. Linklater is good with pacing, but he isn’t much of a visual stylist, and a montage of Gary adopting various disguises and duping hapless suckers doesn’t accumulate the necessary snap. But then into a diner strolls Madison (a blazing Adria Arjona), and this cheerful, unassuming movie heats up in a hurry.

It seems strange to classify Hit Man as a romantic comedy, given that it unspools a noirish plot involving a femme fatale, an abusive husband, a dead body, and some suspicious detectives. (As seen here, the entire New Orleans Police Department seems to comprise four people; Linklater happily sacrifices procedural realism in favor of emotional honesty.) But once Madison starts spending time with Gary—who adopts the alias Ron, first to dupe her into a confession (which he impulsively short-circuits to spare her from prosecution), then to keep up his façade as the titular killer—Linklater shifts the picture’s tone from inquiring to sizzling. It isn’t just a matter of sex, though Madison and Gary/Ron do spend a good deal of time vigorously removing one another’s clothes. It’s that ineffable thing called chemistry—the mutual desire that builds with every glance, to the point where simple dialogue scenes carry an erotic charge.

This is where the actors come in. Arjona, as she showcased all too briefly on Irma Vep, might be one of the sexiest women in the world—her delivery of the line “Welcome to Madison Airlines, please unbuckle your seatbelt” has lodged itself into my brain’s prurient recesses—and she imbues Madison with an allure that lends credibility to the plot’s more questionable turns. Yet it’s Powell who really makes the movie work. Yes, the dude is a dreamboat, with soft green eyes and a surfboard for a stomach (more like Hot Man amirite?), but here he doesn’t just coast on his good looks; instead, he pulls off something of a magic act.

“Who the fuck is Gary??” someone shouts as our hero’s cascading identities start to cave in on themselves. It’s a funny moment; it’s also a fair question. The tension of Hit Man derives not just from whether crimes will be solved and killers will be captured, but from how Gary’s personality changes as he commits more intensely to his alter ego. (Early on, we see him passing an intersection whose streets are named Piety and Pleasure; talk about a crossroads!) Ron, as he’s initially constructed, is basically Gary’s opposite: powerful, menacing, confident. But could these muscular qualities have been residing inside Gary all along? The brilliance of Powell’s performance lies in how deftly he collapses the two characters while still distinguishing between them; with invisible gradations in his bearing—the strength of his posture, the breadth of his smile—he conveys a man who is knowingly playing a role and also losing himself inside it.

Linklater embellishes this process in ways both playful and provocative. One of the best jokes in the movie is that over the course of its runtime, Gary’s philosophy seminar grows increasingly robust, as droning lectures in drab classrooms give way to thoughtful discourse in vast auditoriums. (As one student whispers: “Excuse me, when did our professor get hot?”) But Linklater also takes Gary (or is it Ron?) and Madison’s relationship seriously, investigating whether it’s a mere fantasy or a genuine love story.

For well over an hour, Hit Man’s narrative progression seems predictable; after all, it’s only a matter of time before Madison uncovers Gary’s duplicity, at which point the shit will surely hit the fan. Yet the script has some surprises in store, blending its criminal and romantic elements in a way that leverages the principals’ hot-blooded rapport. This culminates in the movie’s best sequence, in which Gary and Madison stage a recorded conversation via cell-phone coaching—an exhilarating medley of intelligence, intensity, and choreography.

The conclusion of Hit Man is rather less punchy, favoring pat resolution over thorny complexity. But any good romantic comedy compels you to root for a happy ending, and here Linklater’s crowd-pleasing instincts feel sincere, not manipulative. It’s only fitting that he and Powell end up embodying both facets of their protagonist. Like Gary, they’re selling you an illusion; like Ron, they make that illusion feel awfully sexy.

Grade: B+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.