Midway through Venom: The Last Dance, the titular symbiote—it’s no longer considered a parasite, given that it’s reached a state of internal harmony with its host, Eddie Brock—gets existential. “Sometimes, I wonder if we could have had a different kind of life,” the personified mass of black goo muses, its guttural growl sounding oddly muted, even gentle. Eddie and Venom are passengers in a van belonging to a dorky nuclear family, and the decidedly quaint behavior they witness—a symphony of dad jokes, stale snacks, and off-key sing-alongs—activates in them a wistful jealousy. If they weren’t always embroiled in superhero shenanigans, might they have a shot at actual happiness?

This is a nice little moment in a movie that is neither nice nor little. As audience members dutifully shuffling into the multiplex for our periodic dose of franchise medicine, we have been primed to anticipate a loud and hectic blockbuster, replete with noisy action and arcane comic-book references and garish special effects. For this reason, Venom’s gesture of self-reflection is purely hypothetical—a temporary respite before we return to the obligatory clashing and crashing. Yet I can’t help fixating on Venom’s fleeting rumination, because I confess to wondering the same thing. Instead of operating as a de rigueur superhero flick, might The Last Dance have subsisted as, well, something else? Maybe a wayward buddy comedy, or a heist thriller, or a road-trip jaunt?

I suppose the answer is obvious, though I’m not sure it should be. Eddie and Venom may have finally achieved a hard-won symbiosis, but the latter is generally regarded as a rapacious creature that latches on to humans and uses its vengeful ferocity to overpower their will. At the risk of grasping onto a reductive metaphor, this Venom trilogy has always been besieged by its own civil war. On one side of the battlefield stands Tom Hardy, the cagey actor who plays Eddie and who also voices the anarchic alien that inhabits him. Arrayed against him is the fearsome might of the Marvel machine, with its continuity mechanics and genre imperatives and rigorous fan service. This isn’t really a fair fight, even if Hardy has long done his best to make it one.

Over the course of three films, the relationship between Eddie and Venom has evolved, shifting from wild antagonism to grudging partnership to something resembling friendship. That might seem to hamper this trilogy capper, as it’s easier for Hardy and the filmmakers (the screenwriter here is Kelly Marcel, also making her directorial debut) to generate goofball odd-couple antics when its principals are hostile rather than collaborative. But there are stretches of The Last Dance that are surprisingly pleasant, verging on charming. Hardy, no longer feeling compelled to overpower us with the force of his chameleonic talent, has relaxed into the role(s), still flashing his physical and vocal dexterity but without drenching himself in flop sweat. At one point, Eddie and Venom refer to each other as Thelma and Louise, and it works because it’s a throwaway; rather than rubbing our face in the reference, Hardy makes it casual, even as he reinforces the characters’ shared affection.

That particular allusion might mark The Last Dance as a road picture, but while Eddie and Venom do a decent bit of travelling—beginning the film in Mexico, they plan to head to New York but end up visiting Las Vegas and the Nevada desert—the movie isn’t really episodic. It does, however, provide the occasional respite from all its superhero clanging, most notably when its heroes visit a casino and the typically rumpled Eddie struts about in a debonair tux (a winking nod to the James Bond rumors that used to cling to Hardy like, well, sticky goo). This interlude, in which Eddie compulsively plays the slots and then yields his body, Ghost-style, to his hedonistic symbiote for a scene of ecstatic twirling in a penthouse, is the best part of The Last Dance, precisely because it has nothing to do with the rest of the movie.

About which, I can scarcely summon the energy to discuss. The big bad of The Last Dance is Knull (Andy Serkis), a Thanos-like brute who’s imprisoned on a faraway planet. For reasons I refuse to even try to comprehend, Knull unleashes an army of animal mercenaries—they look like a cross between the monsters of Kong: Skull Island and the skittering aliens of Starship Troopers—in search of a MacGuffin, which apparently can only be retrieved by killing Eddie and/or Venom. The stakes of their mission are purported to be not just large but cosmic; we’re repeatedly informed that if Knull’s snarling emissaries succeed in their goal, the entire world will be annihilated.

Who cares? I don’t mean that rhetorically; I’m honestly wondering what percentage of viewers might be invested in yet another cataclysmic plot that involves secret government bunkers and hinges on a mystical glowing orb and traffics in made-up words like “Xenophages.” The bargain we’ve long made with the Marvel Cinematic Universe (of which the Venom franchise isn’t technically a member, for now) is that, while it will sate fanboy appetites by delivering fantastical comic-book spectacle, it will also provide more earthly pleasures in the form of quippy dialogue, intelligent actors, and even the occasionally resonant theme. (Cool images might also have been nice, but the MCU house style generally disdains visual ingenuity.) The cacophonous set pieces and multiversal convolutions in pictures like Spider-Man: No Way Home and Deadpool & Wolverine are the price that must be paid for us to enjoy all of the human elements—the bickering, joshing, and bonding. That stuff can be fun and tasty, but it is also required to be a side dish. The main course remains one designed to satisfy loyal customers who crave the genre’s meatier provisions: the callbacks and crossovers, the recognizable costumes and mid-credits teases, the esoteric references and computer-generated bolts of lightning.

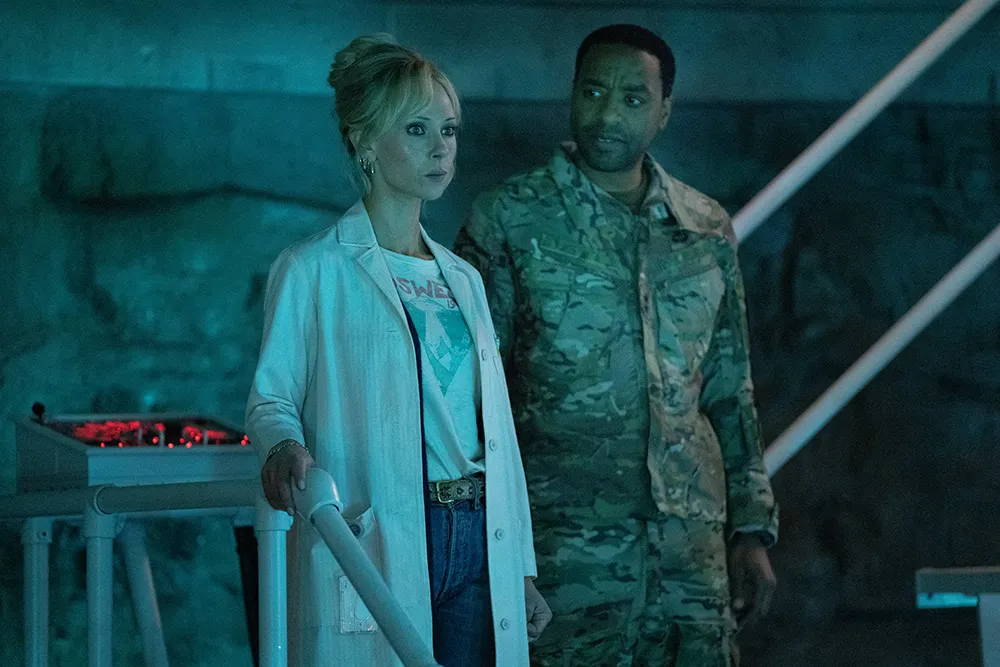

These are the terms of the unwritten contract that defines superhero cinema, and I’ve grown to accept them. (Seriously: I think quite a few Marvel movies are pretty good.) But did they really need to extend to fucking Venom? I confess that my nerdery, while vast, doesn’t encompass the realm of comics, so it’s possible that I’m underestimating the degree of enthusiasm with which viewers will cheer the appearance of Knull, or Dr. Teddy Payne (Juno Temple), or General Rex Strickland (Chiwetel Ejiofor, getting downgraded after popping up in the MCU proper in Doctor Strange and its sequel). Yet I am dubious that most viewers, when greeted with the sight of Tom Hardy losing control of his limbs while mixing himself a cocktail, would demand that the action pivot away from such whimsical farce and toward tedious info dumps and sterile research facilities and gigantic aliens who scan for their prey in a kind of smell-o-vision that renders the screen a ghastly grey.

Admittedly, I would be more tolerant of this transition if the franchise elements of The Last Dance were less execrable. But whether Marcel is indifferent or capable, her staging of the large-scale sequences is numbingly familiar and distressingly chaotic. There are a few striking images (a possessed horse, an acid shower), but there is no clarity to the action, which instead unfolds via screeching clamor and weightless effects. The climax is particularly wretched, an unrelenting barrage of extraterrestrial violence that carries no visual coherence or wit. A single scene of this is tiresome; a non-stop half-hour is downright torturous.

Did it need to be this way? It isn’t fair to say that Venom: The Last Dance lacks a personality, because Hardy’s energetic and syncopated performance imbues it with a quirky flavor. (The soundtrack is curiously partial to the late ’60s and ’70s, with tunes from Queen, David Bowie, Cat Stevens, and ABBA.) But while Venom is best known for its bravado, the ultimate tone here is one of cowardice—the dutiful hitting of standard superhero marks, for fear of otherwise offending comic-book aficionados. Eddie and Venom may have developed a mutual respect, but the vibe here is less symbiosis than surrender.

Grade: C

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.