Kubo and the Two Strings: In a Land of Magic, a Storyteller on the Run

The opening voiceover of Kubo and the Two Strings admonishes viewers not to blink. Closing our eyes, we are told, will result in the death of the film’s hero. It’s a bold gambit that could potentially induce groans from the audience, were it not accompanied by a ravishing image: a woman and her baby in a tiny canoe, surging forward against a giant wave, as rain lashes down and the moon shines ominously. It’s an enthralling sight, one that renders the narrator’s warning superfluous—who could possibly look away from such a scene? But that narration, beyond establishing the life-or-death stakes, speaks to the movie’s larger purpose. Kubo and the Two Strings isn’t just a story about an artist. It’s about how artists tell stories.

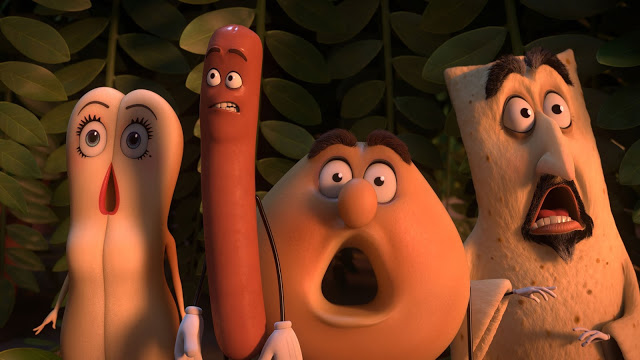

The artist-in-chief of Kubo is Travis Knight, the CEO of Laika, a studio that occupies a unique space in the American cinematic landscape. Eschewing the digital wizardry of Pixar and DreamWorks, Laika instead makes movies via stop-motion animation, that laborious method of physically manipulating individual objects for illusive effect. (This playful scene illustrates just how mind-bogglingly arduous the technique is.) Its first three films—Coraline, ParaNorman, and The Boxtrolls—married this painstaking approach to an off-kilter weirdness, resulting in distinctly original pictures that were always interesting, if not quite astonishing. But Kubo and the Two Strings, which is Knight’s directorial debut, is the studio’s best movie yet, combining the doting meticulousness of its prior works with a sweeping, stirring narrative and richly drawn characters. The style may be new-fangled, but the storytelling is old-fashioned in the best ways. Read More