In 1972 in Iceland, Bobby Fischer attempted to become the first American-born man to win the World Chess Championship, seeking to wrest the crown from imposing Soviet grandmaster Boris Spassky. Now, if you think that sounds challenging, try making a movie about it. Sure, sports films are only tangentially about the sports themselves, but they almost always revolve around some degree of dynamism or athleticism, some sort of physical heroism for the camera to capture. But Pawn Sacrifice, Edward Zwick’s dramatization of Fischer’s famous battle against Spassky and the Iron Curtain, is about chess, which is basically the least cinematic sport imaginable. Zwick’s seemingly impossible task is to transform a thoroughly sedate affair—one in which two men stare at carefully sculpted figurines, furrow their brows, and think—into an actual thriller of tangible urgency and excitement. He mostly succeeds. Functional, beautifully acted, and curiously engrossing, Pawn Sacrifice resembles the best traditional sports movie Zwick possibly could have made on this subject. In other words, it isn’t half-bad.

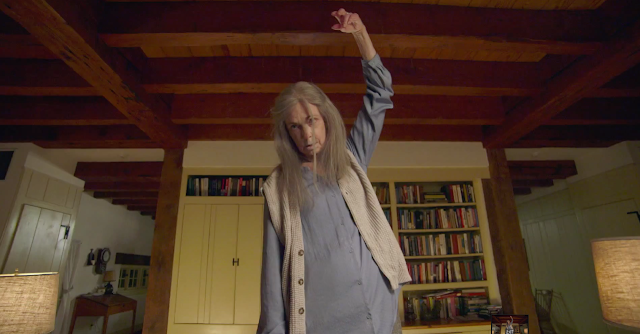

The film opens in medias res, after Fischer has forfeited the second game of the Championship (the rules provided for up to 24 total games) and has barricaded himself in his rented cottage, flinching at the slightest sound. It then flashes back to his childhood in New York, a predictable device that immediately illustrates both the benefits and the drawbacks of Zwick’s orthodox approach. The flashback, which is mercifully brief, does its job: It bluntly illustrates that Fischer (played as a young boy by Aiden Lovekamp and then as a teen by Seamus Davey-Fitzpatrick) is both a genius and a prick. Expressing the former element proves problematic for Zwick; unable to telegraph Fischer’s virtuosity visually, he settles for dialogue, with adults repeatedly gushing about the boy’s brilliance, followed by a montage of handshakes soundtracked to laudatory notices from newscasters. (To be fair, Zwick initially toys with using graphics to convey Fischer mentally maneuvering pieces on the chessboard, but it’s a gimmicky tactic that he wisely abandons.) But he efficiently articulates Fischer’s petulance, as when the youth loudly berates his mother without a hint of remorse. This kid has no time for sensitivity—he has chess to play. Read More