At one point in Peter Berg’s geopolitical action thriller The Kingdom, Jamie Foxx tells a Saudi official, “America’s not perfect, but we are good at this.” The “this” he’s referring to is criminal investigation, but as Berg’s career has gone on, his films have played as a variation on this central theme of American competence. He makes movies about strong-willed, muscular men and women who excel at problem-solving and crisis management. It’s historical fiction with a nationalist tint; in recreating specific, disastrous events, Berg venerates the broader (and, in his view, distinctly red-white-and-blue) virtues of teamwork, loyalty, and perseverance. The guy who played Linda Fiorentino’s hapless patsy in The Last Seduction has somehow fashioned himself into American cinema’s chief patriot.

Well, maybe vice-chief. Berg’s current leading man of choice is Mark Wahlberg, our great nation’s consensus avatar of blue-collar heroism. In Lone Survivor, the fact-based story of a kill mission in Afghanistan gone awry, Berg put Wahlberg through an especially brutal ringer, chronicling how a brave solider used his strength and his smarts to avoid seemingly certain death. Now the director and his star have returned with Deepwater Horizon, a meticulous reenactment of the explosion (and resulting oil spill) that destroyed a rig off the coast of Louisiana in 2010. The names may have changed, but Berg’s template remains the same: Deliberately establish the players and the setting, then scrupulously illustrate how everything gets blown to hell.

If that makes this movie sound simplistic, it is, but only from a storytelling perspective. If anything, Deepwater Horizon suffers from a surfeit of detail. Gruff, no-nonsense characters are constantly throwing around nautical jargon, yammering about negative pressure tests, kill lines, drill pipes, and blowout preventers. It’s complex, inside-baseball stuff, though Berg cleverly attempts to orient his lay audience, not through ponderous voiceover, but through an early expository scene where a 10-year-old girl rehearses a presentation for her science class, cheerfully chirping about what her daddy does for a living. That daddy is Mike Williams (Wahlberg), a simple man who lives an enviably simple life, and who is happily married to Token Supportive Wife Felicia (Kate Hudson, doing what she can with the usual thankless role). The film’s opening passages—where Mike and Felicia first make gentle love, then watch with pride as their daughter outlines Mike’s duties as an electronics technician on the titular oil rig—is a vision of exaggerated domestic bliss, one designed to establish Mike as a Real Person instead of just a hunky slab of selfless virtue.

It’s a noble effort with dubious results. Characterization is not Berg’s strength, and depth is not Wahlberg’s. But together, they’ve discovered how to best exploit the actor’s limited range, and if Wahlberg never renders Mike three-dimensional, he at least gives him a vanilla decency that makes him worth rooting for. The same is true of Andrea (Jane the Virgin‘s Gina Rodriguez, quite good), a no-frills woman who knows her way around an engine. As Deepwater Horizon opens, Mike and Andrea are both headed to their jobs for Transocean, an offshore drilling contractor currently operating in the Gulf of Mexico. They’re 43 days behind schedule, a delay that consternates their present employer, a little corporate behemoth that’s officially named British Petroleum but which is best—and perhaps most virulently—known as BP.

Sound familiar? It should, and not just because this story was headline news. Just last month, Clint Eastwood gave us Sully, a dramatization of a near-calamity that artificially pitted the humble heroism of a brilliant pilot against the institutional rot of a corrupt bureaucracy. Deepwater Horizon follows a similar blueprint, but to Berg’s credit, the conflict here feels more genuine, and the outrage more justified. The facts help; it’s difficult to conceive of a more lopsided moral battle than the one presented here, which finds a crew of industrious American laborers chafing under the yoke of a venal oil company. But Berg also uses sly casting to personalize this righteous struggle. Essentially, the thrust of Deepwater Horizon—its causal explanation for the disaster it depicts—comes down to a choice of who is more trustworthy, John Malkovich or Kurt Russell.

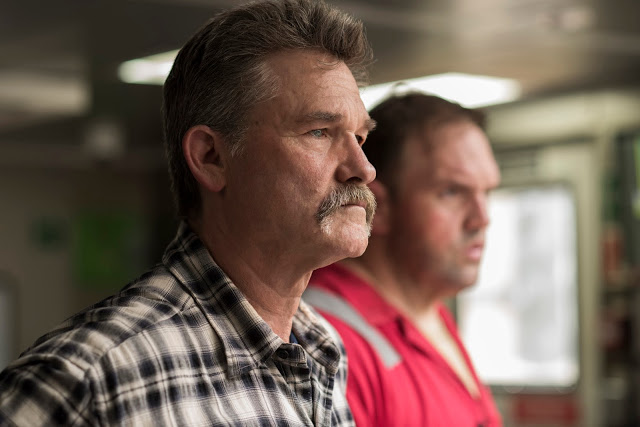

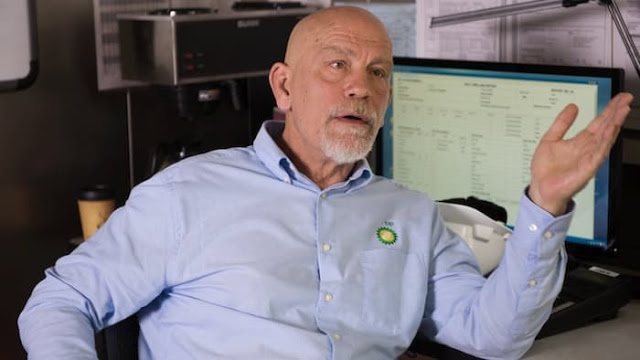

The answer, I should hope, is obvious. Russell, our own reincarnated Wyatt Earp, is practically a nationally recognized symbol of blunt, mustachioed integrity. (He even has experience in this sort of maritime disaster movie, serving as the hardy protagonist in Wolfgang Petersen’s Poseidon.) Here he plays Jimmy Harrell, the head of the Transocean crew—his subordinates adorably call him “Mr. Jimmy”—and an intuitive professional who puts the safety of his employees above all else. His caution puts him at odds with Don Vidrine (Malkovich), a smarmy BP bigwig who waves off Mr. Jimmy’s concerns and pointedly reminds the drillers that there’s an ocean of oil under their feet, and they’re being paid to go get it. So I ask again: Whom should you trust?

Deepwater Horizon‘s vilification of BP may feel like a lazy device employed by Berg’s screenwriters (Matthew Michael Carnahan and Matthew Sand), but it’s a satisfying one, and Malkovich—in a deliciously hammy, Cajun-accented performance—sells it effortlessly, making Vidrine unnervingly intelligent as well as shockingly amoral. His freighted bickering with Mr. Jimmy is the highlight of the film’s first hour, which plays like an extended setup to a horror movie. The muggy Louisiana air is thick with foreshadowing as well as humidity, as Berg systematically walks us through the series of financially motivated events that will lead to the rig’s inevitable explosion. His filmmaking is by no means subtle—repetitive underwater shots of mud rumbling beneath the rig suggest a sinister monster similar to the POV menace in The Evil Dead—but it’s effective at building tension, even if we all know what happens next.

Unfortunately, what happens next is where Deepwater Horizon starts to sink. The film’s second half is designed to be both intensely hellish and rigorously pragmatic, showing how Mike, Andrea, Mr. Jimmy, and others attempt to escape an inferno in the middle of the ocean. This is where Berg is supposed to distinguish himself from other directors; one of the best things about Lone Survivor was that its battle sequences were uncluttered and precise, forgoing the usual mass mayhem in favor of careful choreography. But here, the post-explosion scenes are, quite simply, a mess, a jumble of indecipherable locations and random destruction. Undoubtedly, Berg sought to incorporate an element of chaos into the proceedings, the better to bring us inside the headspace of his panicked characters. Yet that doesn’t excuse his apparent lack of command. Even in the most nightmarish disaster sequences in cinema—the opening invasion of Saving Private Ryan, the plane crash in Flight, even the water landing in Sully—the chaos is invisibly controlled, the director balancing the need to manufacture terror with the equally important need to communicate that terror to the audience. But in Deepwater Horizon, the bedlam doesn’t feel terrifying. It just feels sloppy.

Part of the problem may lie in Berg’s obsession with verisimilitude. I have faith that he has rendered the terrible destruction of the Deepwater Horizon with painstaking veracity, and if I were an oil rigger, I imagine that I would appreciate his diligence. But as a blissfully ignorant moviegoer, I am less concerned with historical accuracy than with visual clarity, and in focusing so myopically on recreating the rig’s collapse, Berg has failed to dramatize it with the necessary filmmaking logic or spatial coherence. It is telling that the movie’s most enjoyable and suspenseful scene—in which Mike and Andrea must ascend the rig before leaping off it to avoid the fire belching below—is also its least plausible. (It is tantalizing to wonder how the project’s original director, J.C. Chandor, might have tackled these scenes, given the bracing lucidity he brought to the genre elements of A Most Violent Year; Chandor bowed out due to creative differences.)

The muddiness of Deepwater Horizon‘s action only makes its other flaws more glaring. Once the flames start to roar and the blood begins to spill, the movie’s relentless demonization of BP grows increasingly shrill; a scene where Vidrine and his cohorts prevent Transocean workers from boarding lifeboats feels ripped straight out of Titanic. And the saccharine denouement again finds Berg slipping into his worst instincts, his strident jingoism matched only by his strenuous need to make you cry.

I didn’t, but I do mourn the apparent demise of Berg’s studious craft. Early next year, he and Wahlberg will be returning with Patriots’ Day, in what appears to be yet another bicep-powered dramatization of a recent American tragedy. That may be of questionable taste, but I won’t rush to judgment, and besides, I haven’t yet given up on Berg. He’s not perfect, but he’s better than this.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.