Is Scarlett Johansson superhuman? In recent years, the one-time ingénue from Lost in Translation has played an assortment of otherworldly women who fit the bill—the sociologically curious alien of Under the Skin, the cerebrally enhanced anomaly of Lucy, the preternaturally gifted warrior of the Avengers films. (The only foe whom Black Widow can’t seem to conquer is the studio that refuses to green-light her own franchise.) But even beyond her portrayals of these exceptional characters, Johansson herself has demonstrated an uncanny, seemingly inhuman ability to dig, well, under the skin, to invest her fantastical creations with quiet longing and simmering grief. That talent proves crucial to Ghost in the Shell, yet another futuristic flick about a faux-human figure wrestling with the concept of her own identity. On the page, the film’s heroine is a fascinating but familiar archetype. Johansson makes her a character.

Good thing, too. Repurposed from the hit Japanese anime from 1995, Ghost in the Shell is a brisk and surprisingly contemplative affair, but it doesn’t have much original to say about the (in)human condition. It’s easy to perceive its central story—set in a glossy dystopia where man and machine have melded—as a greatest-hits compendium of classic science-fiction cinema. There’s a dash of the chilly aesthetic of Blade Runner, a pinch of the caustic irreverence of RoboCop (though lacking the broad comedy of The Fifth Element), a heaping of the cyberpunk chic of The Matrix. Yet despite its composite nature, the dark and sleek universe of Ghost in the Shell still manages to look and feel reasonably novel. It borrows, but it doesn’t steal.

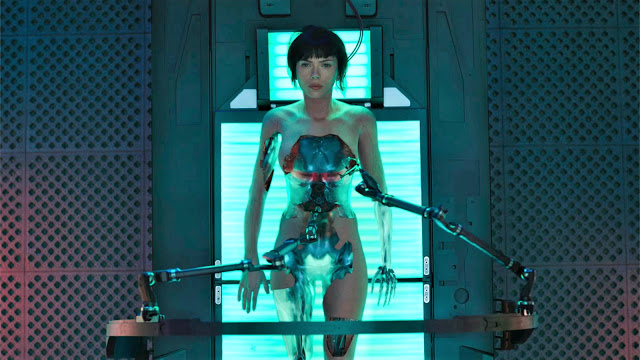

That semantic distinction might appeal to the marketing department of Hanka Robotics, the sleazy corporate superpower of this grave new world. It’s the kind of monolithic industry giant that seems to function as its own branch of government, a tech startup devoted to invading your privacy and also resurrecting the dead. Well, not exactly—as Dr. Ouelet (Juliette Binoche) explains during a relatively painless info dump, Hanka has perfected a procedure that can transplant the still-functioning brains of recently deceased people into healthy synthetic skeletons. Thus is born Major Killian (Johansson), an android with a human brain housed inside a cyborg’s body.

And what a body! Conceptually, Ghost in the Shell may strain for depth and maturity, but its costumes (designed by the duo known as Kurt & Bart, who worked on the last two Hunger Games films) seem to have been tailored explicitly to the impure thoughts of teenage boys. Throughout the film, Major strides through the computer-generated scenery in an array of slimming outfits, the most eye-popping of which is a skintight, flesh-colored leotard that makes Black Widow’s leather look grandmotherly. Yet while Johansson wears her wardrobe well—her beauty doesn’t diminish her fierce, supple physicality—the real showstopper is her surroundings. Director Rupert Sanders (Snow White and the Huntsman) and his production designer, Jan Roelfs (Gattaca), have conceived a dazzling world that is both recognizable and entirely unique, a teeming cityscape clogged with high rises, seedy clubs, and dank alleyways. Their most astonishing touch is the superimposition of enormous holographic figures across the skyline, spectral beings that seem to loom over this gleaming metropolis without possessing any actual corporeality.

Sanders never bothers to clarify those apparitions’ purpose, which is the right move, especially because the more Ghost in the Shell explains itself, the more dreary and plodding it becomes. Major works as a counterterrorism operative, pursuing a shadowy enemy called Kuze (an unrecognizable Michael Pitt), who can somehow export his consciousness into others’ bodies. Major is the ultimate weapon in espionage, a peerless combination of brains and brawn—she can crash through walls, but she can also cloak herself in a stealth technology that seemingly makes her invisible—but her commitment to her mission grows less definitive. “I give my consent,” she declares rotely at the beginning of the film, allowing Dr. Ouelet to access her code, which is to say her thoughts and memories. Yet as the chase intensifies, she begins questioning her orders. Who is Kuze? Why does Hanka want him dead? Is there anyone she can truly trust? And why does her programming keep glitching, resulting in visions of a mysterious hut?

The gradual revelations that provide the answers to these questions are not especially interesting or surprising. (This just in: Trust no one!) Major’s hunt for the truth—which involves implanted memories, stolen identities, and an exceedingly uncharismatic villain—has a vaguely predetermined feel. But what happens is less interesting than how it happens, and despite its boilerplate narrative, Ghost in the Shell manages to stave off mundanity. Sanders is not a particularly impressive action director—the film’s climactic fight scene, involving a clumsily clambering vehicle called a spider tank, is dimly lit and incoherent—but he nevertheless enlivens his set pieces with eccentric flavor. In one fun scene, Major turns a stripper’s pole into a springboard for mayhem, while in another, her confederate, Aramaki (“Beat” Takeshi Kitano, bringing some Yakuza-style grit to a glitzy affair), defeats a new-age threat by brandishing a splendidly old-fashioned six-shooter. And while you may have previously seen variations on Major’s opening assault, it’s unlikely that you’ve seen anything like her target, a mechanical geisha that suddenly transforms into a spindly robotic tarantula.

Besides, while Ghost in the Shell may intimate toward notions of comic-book franchise glory, it is not primarily concerned with action. It is instead a strangely meditative movie, exploring Major’s burgeoning identity crisis with sincerity and sensitivity. Again, this is nothing new—ever since Metropolis, robots on screen have chafed at the directives of their creators—but Johansson lends Major’s predicament a shiver of genuine pathos. In the film’s most stunning scene, Major picks up a prostitute for the sole purpose of caressing her face, and Johansson turns her own visage into a rippling river of confusion, sadness, and desire.

That gorgeously haunted face is, of course, white; the casting of an American actress in a big-budget production based on a Japanese anime has caused no shortage of controversy. While I will defer to more qualified commentators on the propriety of this decision, I will note that the concept of whitewashing has actually been baked into the film’s plot, with a third-act reveal that will doubtless enrage some viewers but that remains, from a certain perspective, powerfully executed.

Whether this is a sign of Sanders’ awareness or his ignorance is an open question, which makes it oddly fitting for Ghost in the Shell, a movie that poses a number of legitimately thoughtful inquires—about the intersection of humanity and technology, about the tension between the individual and the state—but can’t quite figure out how to answer them. It’s turgid and tedious in spots, but it’s often dazzling and always beautiful. And while it never fully satisfies, it repeatedly probes and pricks, activating random areas of your brain that you’d expect to remain dormant while watching yet another dystopian yarn. That may sound invasive, but I give my consent.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.