Helmets matter in Star Wars. The Walt Disney Company knows this; The Mandalorian, the flagship series of Disney’s new streaming service, begins each episode with a retrofitted logo, a montage of recognizable head coverings from our favorite faraway galaxy. J.J. Abrams knows it too. So when an early scene in The Rise of Skywalker, the ninth and (supposedly) last entry in the Star Wars saga, features Kylo Ren (Adam Driver) donning a re-forged black mask—the same mask that he destroyed in a fit of pique one film ago—it is impossible to miss the metaphor. Every modern franchise production must to some extent honor the loyalty of its patrons, but The Rise of Skywalker exhibits a peculiar brand of fan service. It appears designed to cater not to Star Wars enthusiasts at large, but to the small and vocal sect of devotees who adored the seventh episode, Abrams’ The Force Awakens, yet who simultaneously despised its follow-up, Rian Johnson’s The Last Jedi. If Johnson wielded spunk and irreverence to blow the franchise template to bits, Abrams deploys nostalgia and traditionalism to put the pieces back together.

This is not all too easy. Just as that reconstructed helmet still shows visible cracks, The Rise of Skywalker is a seamy and uneven movie, laboring to bring the saga to a stirring close while also frantically course-correcting toward a more conventional version of the Star Wars mythos. Rather than boldly exploring new worlds (whoops, sorry, wrong franchise), it retreats inward, taking refuge in the safe and familiar. This is disappointing, but it is far from devastating. Abrams’ narrative choices may border on cowardly, but he remains a skillful supplier of big-budget imagery and exciting conflict. That he lacks Johnson’s daring and imagination has not precluded him from making another boisterous adventure, with moments of glorious spectacle.

What he hasn’t done is provide us with a sufficiently malevolent villain, or even a new one. Instead, as the customary opening crawl informs us (“The dead speak!”), the big bad here is none other than Emperor Palpatine (Ian McDiarmid), resurrected by some combination of dark magic and Abrams’ affection for The Return of the Jedi. I can’t deny experiencing a certain frisson upon seeing Palpatine again—it is always pleasurable to watch McDiarmid hiss lines like, “Let your death be the final word in the story of rebellion”—but his reemergence is nonetheless dispiriting, an indicator of Abrams’ preference for repetition over creation. Is there another Death Star to vanquish? Not exactly; instead, Palpatine commands a fleet of omnipotent star destroyers, each equipped with the Death Star’s capability to turn planets into dust.

Of course, to paraphrase Darth Vader, the ability to destroy a planet is insignificant next to the power of well-drawn characters. So while Palpatine’s all-consuming evil may be old hat, it doesn’t function as The Rise of Skywalker’s central dramatic axis (nor did it in Return of the Jedi). The film’s far more compelling antagonist remains Kylo, who is still obsessed with his Vaderian goal of turning Rey (Daisy Ridley)—the burgeoning Jedi who previously spurned his offer to serve as his co-tyrant—to the dark side. Abrams, who wrote the screenplay with Chris Terrio (Argo, Batman v Superman), may foolishly retcon a number of Johnson’s braver decisions, but to his credit, he retains and embellishes one of The Last Jedi’s most fascinating developments: the inexplicable psychic connection between Kylo and Rey. This time around, beyond being able to see each other across worlds, the dueling warriors can occasionally influence each other’s actual environments, a wrinkle that Abrams repeatedly exploits to clever effect.

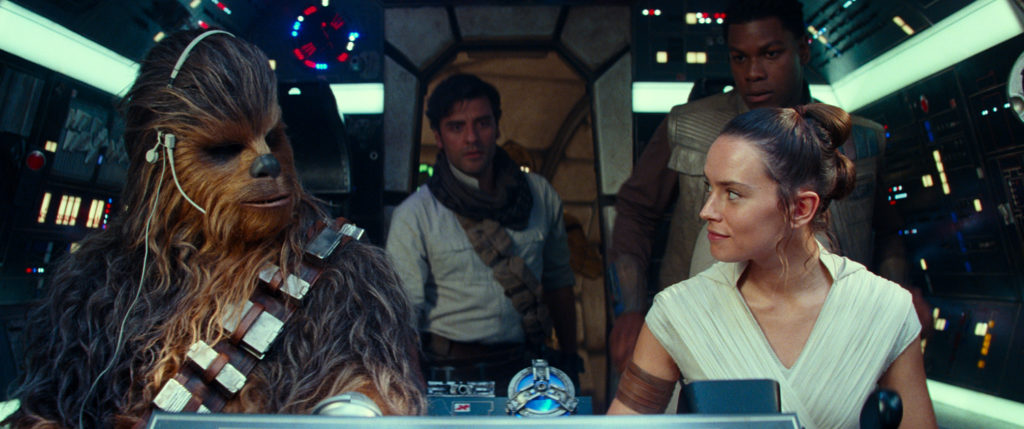

He also lets Rey hang out with the boys again. After some brief setup—including a rather dazzling opening scene which finds Kylo slaughtering unknown foes, to no sound other than John Williams’ fraught and booming score—The Rise of Skywalker sends Rey off on a mission alongside Finn (John Boyega), the former stormtrooper turned Resistance freedom fighter, and Poe Dameron (Oscar Isaac), the ace pilot with the cute droid. All three actors are now supremely comfortable in their interstellar skins, and Abrams gives them room inside the Millennium Falcon’s cockpit to joke, bond, and squabble. It may seem silly, but I welcome a Star Wars movie which, in addition to chronicling yet another battle for the fate of the universe, takes time to ponder if Chewbacca cheats at holochess.

Structurally, The Rise of Skywalker unfolds as a linear quest narrative: Our heroes must find a MacGuffin called a Wayfinder, an interdimensional GPS that will reveal Palpatine’s whereabouts. This results in them visiting a number of planets, each with their own distinctive citizenry and geography. The most interesting of these is Kijimi, a cold and forbidding realm where the soldiers of the menacing First Order have imposed martial law, allowing the film to acquire a shiver of dystopian allegory. It’s also where Poe finally receives a quasi-love interest—sorry, shippers, that blink-and-you’ll-miss-it gay kiss you heard about isn’t between Poe and Finn—in the form of Zorii Bliss, a helmeted (see?!) gunslinger played with winning tartness by Keri Russell. Their sour-but-sweet relationship is emblematic of the movie’s broader character dynamics: playful, reliant on shared history, and somewhat limited in depth.

In fact, it’s when The Rise of Skywalker attempts to dive deeper—and when it seeks to unravel the threads that The Last Jedi meticulously constructed—that it begins to falter. I don’t pretend that Abrams owed Johnson any sort of loyalty, even if it’s a pity that the character of Rose (Kelly Marie Tran) is given very little to do this time around, or that Benicio Del Toro’s slippery thief has been discarded entirely. But there is a difference between artistic independence and blinkered obstinacy; that Abrams possessed his own vision for Star Wars’ future didn’t require him to limit his sights to a tunnel.

This is most galling in his treatment of Rey, or rather her ancestry. Perhaps the most audacious revelation in The Last Jedi—certainly its most meaningful—was that Rey’s parents were “filthy junk traders”, a twist that shattered the idea that Jedi power is a birthright afforded only to a royal few. Abrams, desperate to rework this understanding of Rey’s lineage, scampers to the crowded sanctuary of familial significance, a maneuver that flattens her character and dilutes her symbolic importance. (That’s the thing about sanctuaries: They’re peaceful, but they’re also dull.) “Some things are stronger than blood,” someone wisely intones at one point, but it’s difficult to take that sentiment seriously when The Rise of Skywalker is so fixated on genealogy. It’s ironic that the Wayfinder is a locating device, given that in this particular area, Abrams seems so thoroughly lost.

This storytelling moonwalk—the direction to the audience

that, to quote Yoda, you must unlearn what you have learned—is the movie’s most

glaring flaw, though not its only one. The editing is weird; there’s a runner

about Finn needing to tell Rey something important that never pays off, while some

of the dogfights suffer from the usual issue of anonymous spacecraft exploding at

random. There are intimations of romance, but this galaxy remains a largely

sexless place, which is why a late kiss feels unearned (though the smile that

follows it is rather lovely). There is quite a bit of droid-related humor, involving

not only C-3PO and BB-8, but also a Wall-E-esque

newbie with clear anxiety issues; some of the laughs land—a tiny tinkerer named

Babu Frik (voiced by Shirley Henderson) is a wonderfully anarchic presence—but much

of the comedy lacks the wit of the prior installments (much less the inspired activism

that Phoebe Waller-Bridge brought to Solo).

And our beloved Princess General Leia is mostly sidelined, though this

is hardly Abrams’ fault, given that Carrie Fisher died three years ago. (If

anything, the film’s incorporation of unused footage from The Force Awakens is relatively seamless.)

So, yes, there are problems. But here’s the thing: Stormtroopers fly now.

By which I mean, while The Rise of Skywalker is a decidedly imperfect movie, it is also a blast. Abrams may be a conservative filmmaker, but he is an ace student of Star Wars history, and his cinematic fluency allows him to construct set pieces of extraordinary savvy. (That said, don’t bother paying extra for the 3D conversion, which is utterly perfunctory.) An early scene on a desert planet called Pasaana (so many deserts!)—where our gang runs into a rascally old fellow named Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee Williams, duh)—feels like an intergalactic update on North by Northwest, with Rey fleeing from an incoming spaceship only to literally flip the sequence on its head. It’s a truly thrilling moment, the first of many that combine classical mythology with new-age wizardry.

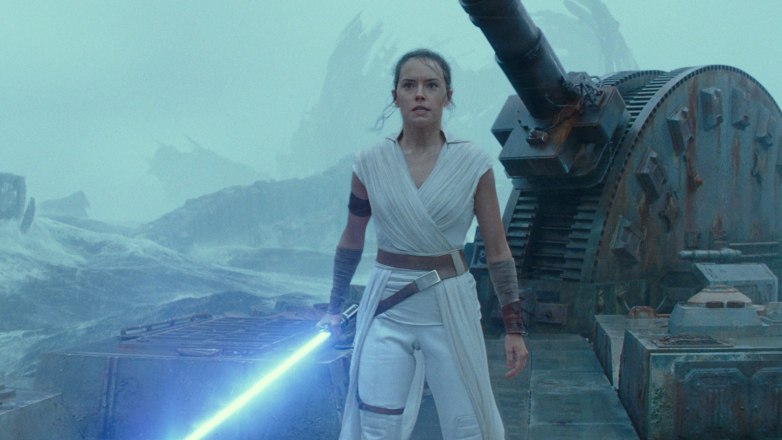

The movie looks cool, too. The Star Wars pictures have always been about the ceaseless struggle between light and dark, and here, that clash isn’t just figurative. Visually, much of The Rise of Skywalker takes place in muted locations—damp caves, sepulchral lairs, windswept beaches—which allows Abrams to punctuate the gloom with pops of color. (The cinematographer is Dan Mindel, who also shot The Force Awakens.) Rey’s lightsaber, activated with that always-satisfying whoosh, functions as a brilliant beacon of contrast, the bright-blue blade illuminating her surroundings while also amplifying the looming shadows that envelop her.

And if you can push past the film’s sense of caution— its paramount insistence on restoring the franchise to its familiar roots—you will find much to admire in its rousing third act, which pays touching tribute to the usual themes of perseverance, hope, and sacrifice. A duel on a docked ship may not be especially kinetic, but it’s loaded with anguish, the waves lashing down at the combatants with stinging fury. As for Abrams’ space battles, they lack the dynamism of the franchise’s best shootouts—the preeminent purveyor of space carnage remains George Lucas—but he nevertheless concocts a delightful Western-style throwback at one point, lending new meaning to the term buffalo soldiers. And while Palpatine’s monotonous evil is frustrating, the final confrontation still features several epic moments, most memorably when Rey delivers a bravura no-look pass that would be the envy of LeBron James.

That sequence involves a lightsaber, the so-called “laser sword” that Han Solo once pooh-poohed as an ancient weapon, and which has acquired considerable thematic weight over the past four decades. Twice in this film, characters fling their sabers away—first into the ocean, then into the flames—but while that freighted action would seem to imply drastic changes, it’s a feint; Abrams is not so intrepid an artist. Yet neither is he untalented. And even as this movie takes comfort in the franchise’s typical beats and rhythms, it also provides stunning new sights and frequent moments of wonder. Perhaps this tonal bumpiness is fitting. After 42 years and a dozen movies, the Star Wars universe concludes not with absolute triumph or crushing failure, but with jagged, qualified success. So be it. The Rise of Skywalker is hardly a masterpiece, but in its own uneven way, it brings balance to the Force.

Grade: B

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.