I take movies seriously, but how seriously should movies take themselves? One of the saws about modern blockbusters is that they’re meant to be dumb fun—that they’re designed to function as a respite from the harshness of reality, and that they grant viewers the blessed opportunity to “turn your brain off.” Setting aside the wisdom of deactivating your central nervous system, I acknowledge that films which operate primarily as pleasure dispensers carry a certain appeal, though it’s debatable whether they need to be dumb—or to neglect more pesky, brainy attributes like plot, theme, and character—in order to be enjoyable. The phrase “it doesn’t take itself too seriously” is generally considered a compliment, implying not that the picture in question is foolish, but that it’s unpretentious.

But is this a sliding scale? That is, when it comes to action—the genre most typically cited by Brain-Off enthusiasts—do movies necessarily trade seriousness for satisfaction? Or can a film’s sincerity instead indicate its level of artistic commitment, suggesting that it approaches its crowd-pleasing task with formal rigor and genuine care? These are false dichotomies, but this past weekend nevertheless presented an intriguing contrast, featuring two new action flicks that occupy opposite ends of this theoretical spectrum. One takes its blockbuster imperative deadly seriously; the other treats seriousness akin to a disease.

As its title suggests, Bullet Train is set in Japan, but it really takes place in Movie World—that heavily stylized cinematic universe which has previously been pioneered by Guy Ritchie and Quentin Tarantino. Based on a book by Kôtarô Isaka (the frenetic screenplay is by Zak Olkewicz), it’s the kind of film where two assassins codename themselves Lemon and Tangerine, then take time to debate which is the superior fruit; also, one of them constantly quotes Thomas the Tank Engine—not to be cute, mind you, but because he earnestly believes that the children’s book series about a smiling locomotive carries valuable insight into human behavior and social order. Whenever it introduces new characters—none of whom possesses a real name but instead receive gangland monikers like The Wolf, The Hornet, and The White Death—it emblazons their epithet on the screen in bold capital letters, signifying the emergence not of a person but of a destructive force of nature.

Our guide to this heightened underworld is Ladybug, a reluctant hit man who bemoans his streak of bad luck (people tend to die around him, can’t imagine why) and resolves to harness more positive vibes. As played with sanguine cheer by Brad Pitt (his handler speaks in the honeyed alto of Sandra Bullock, marking their second collaboration this year), and wearing a bucket hat and dark-rimmed glasses (someone describes him as looking “like every homeless white man I’ve ever met”), Ladybug embodies Bullet Train’s tone of ironic detachment; sure, he’s a scarily gifted killer, but he really just wants everyone to have a nice time. When he dispatches foes to their deaths, which happens quite regularly, he typically does so with a mixture of regret and resignation. Early in the movie, he learns that he’s the target of a crazed drug lord’s yearslong vendetta, to which he replies with characteristic bafflement, “I don’t even know you!”

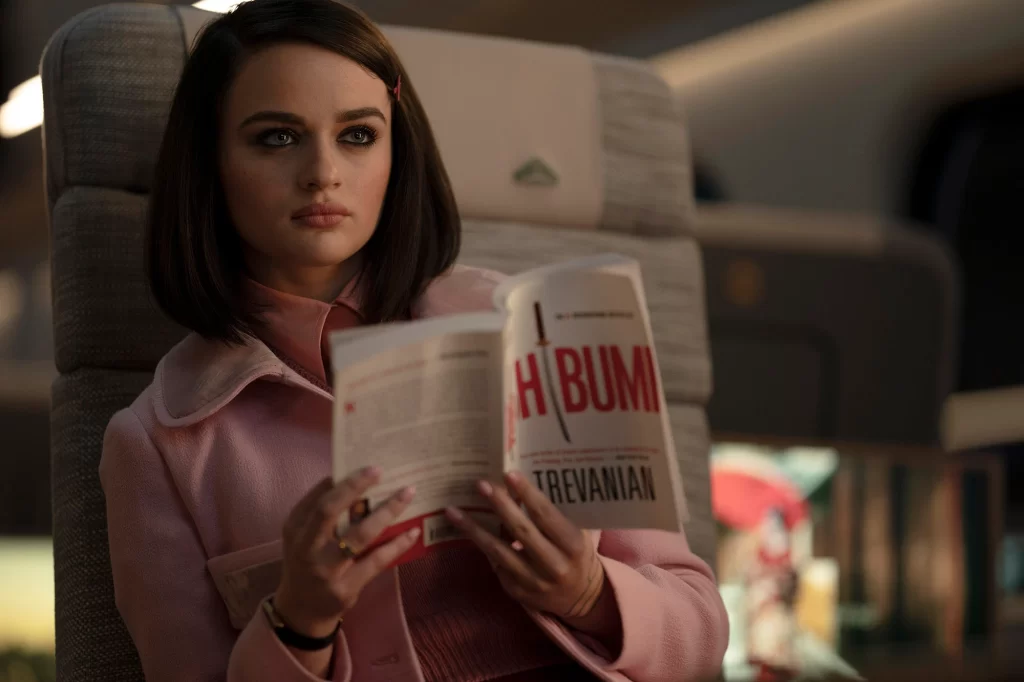

There are a lot of people he doesn’t know. Bullet Train, whose very complicated narrative spirals outward from a very simple premise—all of the characters are desperate to retrieve that most classic of MacGuffins, a briefcase—adopts a maximalist approach in terms of structure as well as style, layering on subplots and constantly circling around in time. In addition to Lemon and Tangerine—whose half-antagonistic, half-affectionate banter is given lively voice and form by (respectively) Brian Tyree Henry and Aaron Taylor-Johnson—the miscreants on board include a sullen yakuza (Andrew Koji), whose son has recently been pushed off a roof; a coquettish teenager (Joey King), whose pink wardrobe and innocent demeanor mask the ferocity of a cold-blooded sociopath; a very angry cartel kingpin (Benito A. Martínez Ocasio, aka Bad Bunny), whose rage stems from the murder of his wife; and an unscrupulous poisoner (Zazie Beetz), who dons an impenetrable disguise and who also evinces a bizarre fondness for the word “bitch.” The movie’s principal bet—placed by director David Leitch, whose high-octane résumé comprises the original John Wick, the euphoric ’80s romp Atomic Blonde, and the smirking sequel Deadpool 2 (plus a noisy Fast & Furious spinoff)—is that repeatedly crashing all of these outsized personalities into one another will produce laughter, excitement, and delight.

It’s a gamble that yields diminishing payoffs. To be fair, as an action movie, Bullet Train isn’t bad. Leitch is a competent fight choreographer, and some of the close-quarters combat—in particular an early brawl between Ladybug and The Wolf, in which that precious briefcase becomes an invaluable shield—is sharply staged, with clear sight lines and lucid editing. There is a welcome emphasis on martial artistry rather than hectic gunfire, and most of the kicks and punches possess tangible weight.

But Bullet Train doesn’t really want to be an action movie. It’s more interested in proving itself as a glib crime picture, and it strives to cultivate a certain sense of cinematic cool. In this, it mostly fails. Leitch breathlessly arrays the artifacts of classic genre disruptors like Pulp Fiction and Snatch—the wraparound flashbacks, the pop-culture references, the winking needle drops (the soundtrack features Japanese covers of “Stayin’ Alive” and “Holding Out for a Hero”)—but he is undone by his own smugness. The film mistakes arch for clever, convinced that bombarding us with stale quips and absurd twists will delude us into thinking that we’re watching something inventive, when in fact this synthetic product hasn’t an imaginative bone in its body.

And yet, I can’t quite bring myself to dislike Bullet Train. It may be shallow and derivative, but it’s at least trying to be entertaining, and to generate thrills through (relatively) original storytelling rather than relying on prepackaged fan interest. Conceptually, it’s exactly the kind of ambitious, big-budget blockbuster I want studios to make. Pity that whenever it threatens to develop momentum, it ends up stalled on the tracks.

If Bullet Train is goofy, flabby, and playful, then Prey—the second feature by Dan Trachtenberg, from a script by Patrick Aison—is tense, streamlined, and grave. Set in 1719 in America’s northern plains, it’s a raw, elemental picture that explores one of cinema’s most ancient conflicts: the misery of being a woman surrounded by a bunch of dicks.

OK, it’s ultimately about something a bit different. But when Prey opens, the primary enemy of Naru (Legion’s Amber Midthunder)—a lithe, skilled Comanche with a Carolina dog by her side and a chip on her shoulder—is the banal evil of misogyny. Naru may be an intuitive tracker and an able healer, but the men in her tribe—including her elder brother (Dakota Beavers), an aspiring war chief—scoff at her soldierly aspirations as unladylike, insisting she devote herself to woman’s work. So when one of her comrades is attacked by a wild animal, she leaps at the opportunity to hunt it down and prove her muscular bona fides. Surely it won’t be dangerous.

There is a parallel universe in which viewers might watch this film cold, with no foreknowledge of its central foundation or existing lineage. But we don’t live in that world, so I might as well come out with it: Prey is a Predator movie. Technically it’s the fifth installment in the series, though chronologically speaking it’s the first, seeing as it takes place more than two centuries before Arnold Schwarzenegger and his beefy band of militants ventured into the Central American jungle and encountered one ugly motherfucker. Regardless, the basic setup abides: Once again, a killing machine from outer space lays waste to a clan of mighty warriors, though the boisterous camaraderie and high-powered ammunition of John McTiernan’s original have now been replaced by something darker and more primal.

This slippery subversion has quickly become something of a calling card for Trachtenberg, who just two films into his career has flaunted a talent for upending franchise mythology. His debut feature, 10 Cloverfield Lane, twisted Matt Reeves’ classic monster-movie mayhem into a taut and claustrophobic thriller. Prey isn’t as revolutionary—in bold strokes, its trajectory of a smart and tenacious fighter battling an indomitable force in the wilderness tracks its progenitor—but its sharpened setting and intense tone allow it to feel fresh rather than repetitive. And unlike Bullet Train, it takes its story and its characters seriously, fleshing out its fantastical premise with a measure of realism. (Curiously enough, The Predator, Shane Black’s jokey 2018 sequel featuring a cohort of motley rogues, is closer in philosophical spirit to Bullet Train than to Trachtenberg’s controlled exploration of the same monster-verse.)

This isn’t to say that Prey is tedious or drab; to the contrary, as an action movie, it absolutely sizzles. Trachtenberg exhibits a canny command of physical space, and of how to seamlessly integrate computer-generated creations into real-world environments, allowing the combat to retain a squelchy, visceral feel. He also takes the cramped intimacy he brought to 10 Cloverfield Lane and brilliantly reshapes it for deployment in a far more expansive location. Prey may evoke the limitless sprawl of pre-industrial America, but its two most breathtaking set pieces—a scene in which Naru scrambles to take refuge from a ravenous bear, and a sequence where she finds herself trapped in quicksand, with only her axe and her wits to save her—are marvels of cloistered, suffocating suspense.

There’s even a little more going on here, though only a little; movies like Prey tend to possess a limited ceiling, capable of pushing their kill-the-killer framework only so far. Still, in this specific context, the Predator itself—played by the former basketball player Dane DiLiegro, and souped up with the usual combination of gnarly prosthetics and nifty special effects—emerges as an unusual and intriguing villain. Unlike the antagonists of typical man-versus-nature films like The Grey or The Revenant, the Predator is not a native creature who embodies the primeval power of the untamed world. Quite the opposite: It is an invader—a malevolent being that wields alien technology (cloaking camouflage, thermal vision, deadly weaponry) to murder for sport in violation of natural law. This sense of desecration allows Prey, which is streaming on Hulu in both English and a Comanche dub, to acquire a shiver of thematic relevance—as does the haunting image of Naru stumbling upon a herd of slaughtered buffalo, their bloody carcasses stripped of their hides.

Bullet Train would doubtless find the solemnity of such an image uncool, but where that movie ultimately collapses under the burden of its own slickness, Prey transcends its genre trappings through the generous application of sincerity. Some of this is thanks to Midthunder, who imbues Naru with fierce pride and steely toughness without neglecting her wide-eyed fear. Yet Trachtenberg’s filmmaking, with its fluid camerawork and sinewy style, better aligns with the Predator itself—confident, remorseless, constantly moving in for the kill.

Bullet Train grade: C+

Prey grade: B+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.