During a quiet moment in Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch, a journalist played by Jeffrey Wright bristles when a television interviewer asks him why he’s written so frequently about food. “Never ask a man why,” he grumbles. Wright returns in Anderson’s new feature, the strange and beguiling Asteroid City (he plays a gruff military general with the onomatopoetic name of Grif Gibson), but his reporter’s distaste for contemplation has been left behind. Instead, the characters in this movie are constantly pondering questions of meaning and motive. Why does a photographer injure himself in a burst of frustration? Why does a brainy teenager constantly invite others to dare him to perform perilous stunts? Why does an alien suddenly appear in the middle of the desert? And above all: Why are we here?

“Here” is a matter of perspective in Asteroid City, which again finds Anderson indulging his penchant for nesting tales within tales, art within artifices. Simply telling an entertaining story is no longer sufficient for him, if it ever was; even Rushmore, his breakout second film released a quarter-century ago, found its amateur-playwright hero obsessed with substantiating his own legend. As it happens, that enterprising yearner was the screen debut of Jason Schwartzman, who stars here as Augie Steenbeck, a gifted photographer with four children, a recently deceased wife, and multiple types of baggage. Schwartzman, with his thin frame and bookish demeanor, is a natural fit for the famously fastidious Anderson (this is their eighth feature-length collaboration), but Augie is a departure, armed with a corncob pipe, a tanned complexion, and a masculine beard that’s so sharply manicured, you wonder if it’s a prosthesis.

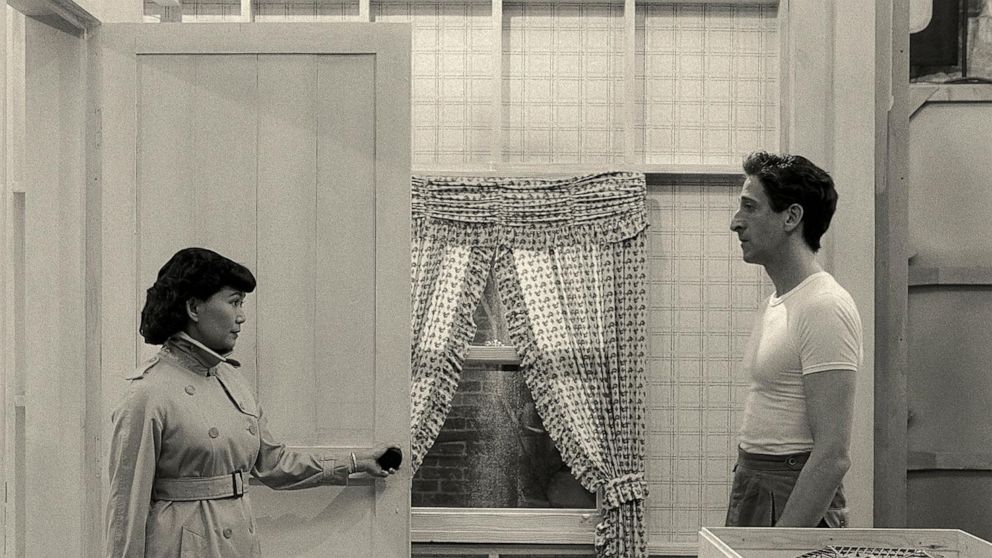

Which, in point of fact, it is. That’s because Augie isn’t just a character in Asteroid City the movie; he’s also a character in Asteroid City the play, which was written by renowned genius Conrad Earp (Edward Norton), and is being shepherded to the stage by maverick director Schubert Green (Adrien Brody). And so, even as he chronicles Augie’s misadventures in the titular Southwest town (the year is 1955), Anderson also explores the process of their fictional development, through the lens of a TV program hosted by a dapper Bryan Cranston. The multiple planes of activity are easy to distinguish—the workshop scenes are shot in black-and-white and framed in the cramped Academy aspect ratio, whereas the resultant desert sequences unfold in glowing color and stretch to the horizon in authoritative widescreen—but they nevertheless tend to blur into one another. This meta approach yields some laughs—at one point, Cranston’s narrator appears in the middle of a sun-spangled location, only to mumble awkwardly, “Am I not in this?”—but it also speaks to Anderson’s broader concern with the act of artistic conception. His brain has become an organ of recursion; each new picture has its own secrets to discover, its own creation myths to unveil.

“Use your grief,” a movie star named Midge (Scarlett Johansson, effortlessly glamorous) instructs Augie when they’re running lines. It’s sound tactical advice, but it also seems to rattle him, deepening the unease that stalks him in both realms. In one of the film’s most striking sequences, Augie—well, really Jones Hall, the actor playing Augie (obviously embodied by Schwartzman)—arrives at Earp’s quarters to audition for the part (it’s here that the beard is revealed as pretense), and together they contemplate the possible reasons for the character’s destructive behavior. (Subsequently, Earp will confess that he can’t decipher how to write a particular scene, another display of choked imagination that inspires a collaborative effort with an acting class.) It’s an intriguing moment, in part for how it leads into a romantic dalliance that’s otherwise left unexamined. Yet it also tugs at the overlap between actor and role, a hazy intersection that later achieves startling clarity when Augie (or is it Jones?) walks off set and finds himself conversing with a former co-star (Margot Robbie), recalling excised dialogue and questioning the purpose of his own production.

If this all sounds a bit hoity-toity, remember that Asteroid City remains a Wes Anderson movie, meaning it’s a resplendent piece of craftsmanship. The black-and-white scenes aren’t as lustrous as those in The French Dispatch, but the contrast emphasizes the blazing colors of the city itself, with its pastel cars and sunbaked vistas. Production designer Adam Stockhausen takes full advantage of the conceit’s theatricality, constructing stylized sets that are both warmly inviting and intoxicatingly strange, as in the highway ramp that abruptly ends 20 feet in midair. The camera (operated by Anderson’s usual cinematographer, Robert Yeoman) glides with the expected degree of precision, as when it introduces us to the arid hamlet by tracking an arriving car, pivoting 90 degrees, and then dollying alongside the quaint buildings like a mechanical tour guide. Anderson’s images tend to be packed with detail, but they also generate power in their simplicity; when Augie phones his father-in-law (Tom Hanks) to discuss his wife’s recent death, they face one another via split screen before turning back to look at the audience, their sadness shifting from communal to isolated.

Where the technique of Asteroid City is a marvel of order and polish, its plot traffics in confusion and panic. Augie’s teenage son, Woodrow (Jake Ryan, from Moonrise Kingdom), is one of five brilliant students who has arrived for a scientific convention, where they will be recognized for their futuristic inventions (jetpacks, ray guns, things of that nature). Ostensibly, it’s a celebratory occasion, but the undercurrent of discomfort that shades the Steenbecks—Augie resolves to finally tell Woodrow and his three witchy younger sisters (played by an adorable set of triplets) of their mother’s demise, casting a pall over the sunny skies—extends to the rest of the town. Asteroid City is a sparkling slice of Americana that’s also the home of busted vending machines, barren cactus-infested lots, and atomic-bomb tests. And don’t forget the small crater that houses an ancient meteorite, the remnants of which spur the arrival (signaled via a marvelous flash of green) of a mysterious visitor—a close encounter that prompts Wright’s commandant to impose a quarantine, sending this cozy settlement into chaos.

What follows is a madcap scramble that’s playful, appealing, and maybe a little frivolous. In terms of narrative, Asteroid City is less conventionally satisfying than some of Anderson’s more cathartic pictures; it lacks the youthful euphoria of Moonrise Kingdom, the clockwork structure of The French Dispatch, the giant heart of Rushmore. But it is nonetheless consistently charming, with a rich vein of humor and an abiding sweetness that never curdles into sap. There are three gentle romances: In addition to the simmering flirtation between Augie and Midge, their respective children strike up a tender courtship (Grace Edwards plays Midge’s precocious daughter), while a young schoolteacher (Maya Hawke) finds herself enchanted by a down-home cowboy (Rupert Friend) who goes by the irresistible name of Montana; the last of these pairings results in a jubilant song-and-dance number, the purity of which surely compensates for any shortage in depth. Yet there is also a tantalizing melancholy at work—a sense of unconsummated longing and thwarted dreams.

Per usual, Anderson has stocked his ensemble with an obscene array of talented actors—Tilda Swinton as an inquisitive physicist, Liev Schreiber as a sulky father, Steve Carell as a chipper property manager, just to name three—but while they’re all delightful to watch, few of them deliver especially vivid performances; they’re plainly playing Wes Anderson characters, with their deadpan reactions and repetitious line readings. (That isn’t a complaint; Anderson’s dialogue hums with snappy energy and rhythmic wit.) The exception, surprisingly enough, is Schwartzman. A gifted photographer (“My pictures always come out”), Augie is one of several Anderson surrogates on screen, but there are layers rippling beneath his quirky genius, and Schwartzman conveys his surface charisma—that he credibly secures the attentions of Scarlett freaking Johansson is quite the achievement—while also hinting at unresolved feelings of uncertainty and discontent.

“We begin with an ink ribbon,” Cranston’s narrator declares during an early shot of Earp seated at his writing desk, “but limited amusement is to be found in watching a man type.” True enough. But for all its stylish whimsy and pictorial beauty, Asteroid City is still very much about that man sitting at a typewriter, concocting yet another story to tell. Augie wants to know why he is the way he is, and if Anderson doesn’t provide any easy answers, maybe that’s because the question is more important. He makes movies in order to search for meaning, and he’ll look everywhere to find it—whether it’s among the aliens up there in the stars, or down here in our own gloriously mundane world.

Grade: A-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.