Denis Villeneuve and Wes Anderson are strangely similar filmmakers, even though they make exceedingly dissimilar films. Villeneuve’s movies are grand, sprawling adventures that envision alien life forms and contemplate dystopian futures. Anderson, by contrast, makes tidy, compact comedies whose foremost exotica are their characters’ eccentricities, and which tend to unfold in an unspecified but highly particular recent past. Yet both directors are true artisans skilled in the craft of cinematic world-building; for them, the screen is a coloring book for their fertile imaginations, one that should be sketched in as boldly and minutely as possible. Put differently, Villeneuve and Anderson treat movie-making like a work of galactic creation. One looks to the skies, the other to the soul, but both construct their own universes, packed with detail, whimsy, and awe.

This past weekend was something of a feast for cinephiles, as it brought new films from the two auteurs, both of which the COVID-19 pandemic had delayed for roughly a year. Villeneuve’s Dune, the long-awaited adaptation of the beloved science-fiction novel by Frank Herbert, finds the Canadian literally building a brand new world, one teeming with wonder and innovation. Anderson’s The French Dispatch, meanwhile, is more earthbound but no less profligate in its assembly. Both are natural progressions that reflect their makers’ career-long preoccupations, yet while both are undeniably impressive aesthetic achievements, only one fully succeeds as a piece of dramatic entertainment.

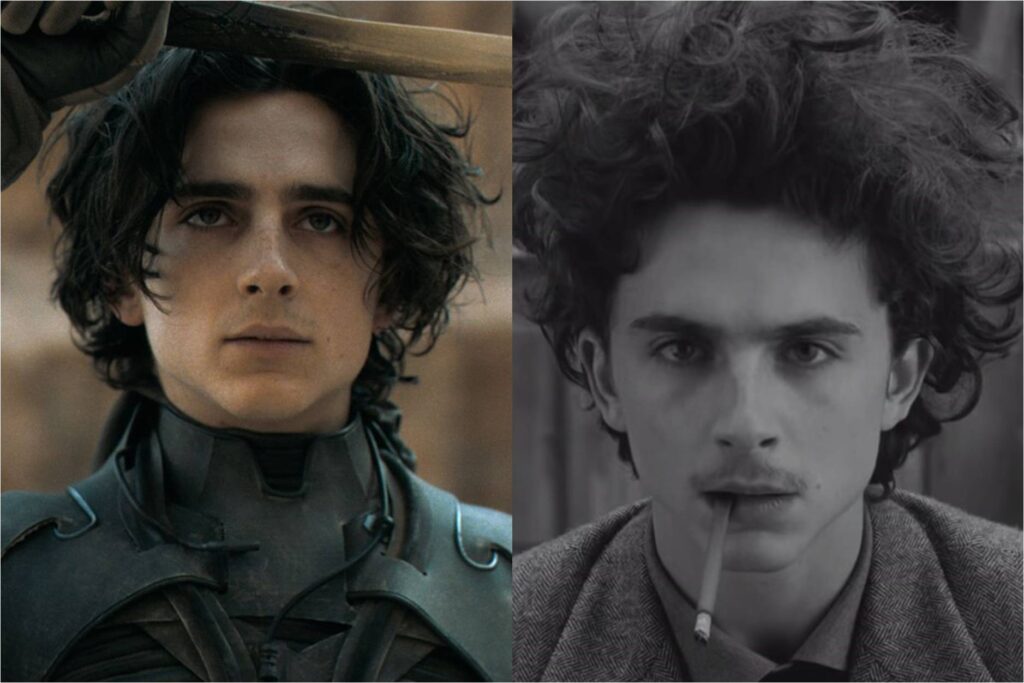

For all its eye-popping glory, Dune’s central narrative arc is familiar, nigh rote. Its sleep-deprived hero, Paul (Timothée Chalamet), is one of those troubled royal types who’s disturbed by dreams of a foreign beauty (Zendaya), and who labors to shoulder the twin burdens of his political future and spiritual destiny. In Paul’s case, those burdens are ancestral, with one flowing from each of his parents. His father, Leto (Oscar Isaac), is the duke of House Atreides, which seems to occupy a middle rung on the ladder of global power that’s topped by an unseen emperor. (This is as good a point as any for me to admit that I’ve never read Herbert’s book, nor seen David Lynch’s much-derided 1984 adaptation.) Meanwhile, his mother, Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson), is a member of the Bene Gesserit, a sect of female warriors capable of bending others to their will merely through command of a rumbled basso called The Voice. Paul thus simultaneously wrestles with the impending obligation of diplomatic leadership and frets over the whispered prophecies of messianic ascendancy.

Which isn’t all that interesting. Chalamet is a nimble actor, and shots of him striding forward in a black cloak amid sweeping scenery carry a certain charge. But Paul’s existential reckoning is old hat, and the character is too feebly written for his predicament to gather any real force. Villeneuve seems uncertain of how best to convey the weight of his protagonist’s anguish; a scene where a religious elder (Charlotte Rampling) arrives and tests Paul’s mental fortitude through use of a mysterious box is appealing in setup, but it mostly results in Chalamet twitching his face while Villeneuve splices in flashes of foreboding visions. It’s difficult to meaningfully distinguish Paul from Luke Skywalker, Frodo Baggins, or any of the other whiny white dudes in modern literature who have reluctantly assumed the mantle of heroism. For him, heavy lies the frown.

Thankfully, Villeneuve exhibits a lighter touch elsewhere. The real pleasures of Dune lie in its spectacle, which is why the movie begins to heat up once Paul and his parents—along with a retinue of advisors, including those played by Josh Brolin, Jason Momoa, and Stephen McKinley Henderson—arrive on the desert planet of Arrakis, where the emperor has tasked them with managing the manufacture of a precious commodity known only as spice. One of the most memorable images of Villeneuve’s prior film, Blade Runner 2049, was of a masked Ryan Gosling weathering a dust cloud and tramping into a sandy wilderness; Dune is essentially that shot turned up to 11. As conceived by Villeneuve and production designer Patrice Vermette, Arrakis is a beautiful and forbidding land, festooned with majestic temples, barely glimpsed monsters, and a delightfully absurd grove of palm trees. And though a few aerial shots of the rolling mounds of earth look a bit too cleanly rendered (shooting took place in Jordan), the planet nevertheless seems tactilely real, a newly discovered world breathing with its own hidden coves and creatures.

This is no small accomplishment, and I mean that literally; the movie is simply massive in terms of scale. Projection screens aren’t any bigger than they were five years ago—if anything, they’re a lot smaller, at least for those who watched on HBO Max—but the world of Dune feels legitimately enormous. That’s harder to pull off than it sounds; would-be blockbuster cinema is replete with anonymous sci-fi flicks that mistake clutter for grandeur. Villeneuve understands how to establish relative size, and when to modulate versus when to go for broke. The pounding score from Hans Zimmer only augments this sense of bigness.

Villeneuve would likely sniff at Dune being dubbed an action movie, but it works best when it’s in motion; it operates more fluidly as a collection of set pieces than a unified story. His eye for color remains extraordinary, not to mention handy; in addition to the blazing orange of the desert, he’s developed a clever red-and-blue scheme for martial combatants based on the invisible force fields that shield them from impact, a nifty method that makes the hand-to-hand fighting more legible. The variety in the film’s costumes also pays dividends, especially during a nighttime invasion where House Atreides finds itself the victim of a devious pincer movement, with white-clothed assassins parachuting down from a fireball-ridden sky. And an early rescue mission, which unfolds clearly and logically, also shows off the film’s ingeniously designed vehicles, especially a quasi-helicopter with rapidly contorting diagonal wings, like a giant metallic hummingbird.

Dune’s dazzling construction is more than just window dressing, but it still can’t entirely salvage the film’s writerly shortcomings. In his recent work, Villeneuve’s great gift has been his ability to tether magnificent images to genuine personal and thematic concerns: the inexorable spread of violence in Prisoners and Sicario, the challenges of human communication in Arrival, the tension between men and machines in Blade Runner 2049. Yet despite some glancing commentary toward the evils of colonialism—the natives of Arrakis are a blue-eyed race called the Fremen, led by a flinty Javier Bardem—Dune lacks that element of provocation. Arrakis is a breathtaking display of world-building, but Villeneuve fails to populate that world with interesting characters. When the people do pop, it’s thanks to the striking visuals; Zendaya’s slippery desert-dweller is more noteworthy for the breathing tube that snakes out of her nose than for anything she says or does, while Stellan Skarsgård’s heavy would be a generic despot were it not for the bulbous masses of fat that gild his body—never more suitably disgusting than when he’s emerging from a vat of black sludge.

Some of this thinness is a product of the screenplay, which Villeneuve wrote with Jon Spaihts and Eric Roth, and which has been designed to cover only part of Herbert’s book, with a recently greenlit sequel to follow. (The on-screen title is “Dune: Part One.”) It’s understandable that Villeneuve wasn’t comfortable cramming the entire novel into a single feature, but the result is that Dune feels like half a movie—maybe even less than half. For such a long film (156 minutes), it’s strangely light on catharsis; instead, the vast majority of it feels like an elaborate setup, saving any real payoff for the conclusion. The two-part structure isn’t unworkable—Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows pulled it off elegantly, with each installment functioning on its own as well as pieces of a whole—but Villeneuve is so committed to buildup that he sacrifices impact. Concluding your movie with the line “This is only the beginning” is meant to be an enticing tease, but here it doubles as an admission of failure.

Not a fatal one, though. Plot, after all, is just one component of a picture, and just as Dune’s ravishing visuals can’t excuse its two-dimensional characters, its flimsy script doesn’t nullify its pictorial splendor. Besides, even if the sequel doesn’t sufficiently flesh out the story, it should still be a thrilling trip to another of its director’s brilliantly realized, faraway worlds. Either way, it’s sure to be a spicy ride.

“Ride” is a word that might apply to the films of Wes Anderson, seeing as they tend to function as mechanized creations—well-oiled, motorized contraptions that whir along carefully placed tracks, steadily accumulating momentum without ever relinquishing control. It’s tempting to accuse Anderson of remaking the same movie over and over, but while his aesthetic sensibility is certainly consistent, his abundant imagination extends to the act of telling vibrantly new stories. The fruits of his painstaking labor aren’t always charming—I must confess that, with the exception of Rushmore, I was something of a Wes skeptic over his first decade-plus—but on the occasions when he successfully marries his obsessive style to his peculiar characters, the fusion of technical prowess and human tenderness can be overpowering. And The French Dispatch is just such an occasion, one of those happy times when Anderson has applied his assiduous technique to yield a true enchantment: exquisitely crafted, yes, but also surpassingly lovely.

If Dune is barely half a movie, The French Dispatch is really three short films in one. Its central conceit is to dramatize the trio of feature stories that appear in the final issue of its titular magazine, whose office is located in the fictional town of Ennui. That name is one of the picture’s more obvious jokes—even Anderson’s most strident detractors could never accuse him of being boring—but it also highlights the gentle absurdity of this fanciful universe; hell, the very existence of the publication, which is technically a satellite of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun, is a prospect that would have seemed implausible even in print’s heyday. Yet in this cheerfully literate and ludicrous world, the periodical thrives under the stewardship of Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray, appearing in Anderson’s work for the ninth consecutive time), whose death prompts his staff to execute his final wish and deliver one last issue comprising three of the weekly’s greatest past essays.

The French Dispatch, then, is an anthology picture. Following a breezy introduction to the habitants and hazards of Ennui (provided by a cycling Owen Wilson), it progresses in three distinct chapters. The first, “The Concrete Masterpiece,” centers on an incarcerated murderer named Moses (Benicio del Toro) whose gift for painting catches the eye of Julien (Adrien Brody), a white-collar criminal with art-world connections. The second, “Revisions to a Manifesto,” follows a youth movement headed by an impetuous idealist called Zeffirelli (Chalamet again, and again talking about his muscles!), exploring his struggles against the establishment even as he flirts and bickers with Juliette (Lyna Khoudri), a fellow student and free spirit. And the third, “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner,” begins as the profile of a famous cook named Nescaffier (Stephen Park) before transforming into a caper involving the commissaire (Mathieu Amalric), whose son is kidnapped by a devious chauffeur (Edward Norton).

Each of these segments carries its own jaunty rhythm, but they are also pieces of a broader symphony, a cacophonous medley of desire, danger, and farce. Anderson is renowned for his rigor, but he has a sneaky impish streak as well; even as The French Dispatch is supremely elegant, it is also wickedly profane. The sequences of delicate camera moves and erudite dialogue are punctuated with moments of spiky violence and ribald humor, as when Berensen (Tilda Swinton), the journalist lecturing an audience on the events of “The Concrete Masterpiece”, inadvertently flicks the projector to a slide of her own naked photograph; shortly thereafter, she departs from her carefully prepared notes and relays a halting anecdote about how Moses tried to rape her. And Moses’ penchant for animalistic growling returns later during a frenetic prison riot, when his fellow inmates quite literally crash the party that Julien is holding for his highfalutin investors.

The level of craftsmanship on display in that sequence—in every sequence, really—is simply remarkable. It has perhaps become easy, as Anderson’s career has evolved, to take for granted the meticulous care that he brings to his compositions, and to the seamless fluidity that he and his regular cinematographer, Robert Yeoman, exhibit when operating the perfectly placed camera. Here, he indulges in an array of playful tricks—split screen, false fronts, kitschy animation—all while maintaining absolute control over the integrity of the image. As usual, he tends to place his actors in the dead center of the frame, lending his shots a mathematical exactitude, while his dollies and pans move at just the right rate of speed. Even a simple scene of a waiter arranging drinks on a tray and subsequently ascending a staircase becomes its own miniature ballet of precisely choreographed sound and motion, while a montage of Moses’ muse (Léa Seydoux) assuming a variety of pliable poses seems destined for a cinematic museum. And the sets, by production designer Adam Stockhausen, are splendid for their combination of intricacy and simplicity.

Nor are the movie’s delights exclusively visual. Anderson wrote the script himself (from a story he conceived with Roman Coppola, Hugo Guinness, and Jason Schwartzman), and it’s a blizzard of verbiage, a ping-ponging barrage of threats, jokes, and insults. (The negotiation in which Julien attempts to buy one of Moses’ priceless paintings is just one example of rapid-fire magic, particularly when Moses tries to set the cost: “Fifty cigarettes. No, seventy-five.”) Between the hectic dialogue and the jam-packed frames, absorbing all of the detail of The French Dispatch can feel like an impossible task, but the sensation isn’t unpleasant; rather, it’s engaging to try to process all of the hustle and bustle. The exhaustion is exhilarating.

Yet Anderson recognizes the value of silence, too. Every so often, he’ll throttle down the lightning pace in favor of tranquility, as when Howitzer shares a quiet moment with one of his writers (Frances McDormand, briefly rejoining her sad spouse from Moonrise Kingdom), or when another reporter (Jeffrey Wright) pauses his yarn to reflect on his sincere admiration of great food. And despite a vocal cameo from Jarvis Cocker, Anderson suppresses his typical urge to flood his work with pop music, leaning instead on large helpings of Bach alongside Alexandre Desplat’s twinkly score.

The French Dispatch is such a gorgeously stylized wonder (did I mention that Saoirse Ronan shows up for roughly 45 seconds, mostly for a single shot of her ice-blue eyes?), it’s possible to overlook the strangeness and complexity of its narrative. The challenge of any anthology film is to tell complete stories which also collectively contribute to a larger thematic whole. Not all of the chapters of this movie are equally satisfying; while “The Concrete Masterpiece” is a triumph of screwball sweetness and “The Private Dining Room” is a marvel of nested storytelling (Wright’s journalist discusses the events on a talk show alongside Liev Schreiber, recalling the layered narration of The Grand Budapest Hotel), “Revisions to a Manifesto” struggles to articulate the specific parameters of its wonky, chess-laced turbulence.

Yet despite their variations in temperament and setting, the three segments are less disparate than they may appear. What gently threads them together, aside from the periodic returns to the magazine’s offices (when the crisp black-and-white chroma briefly reverts to soft color, and when the squarish aspect ratio flares back to widescreen), is a shared appreciation of artistic passion. Moses may be an impulsive psychopath, Zeffirelli a clueless kid, and Nescaffier a simple cook, but their commonality is that their work speaks to people. Whether working with paint, words, or food, their celebrity—the degree of distinction that makes them ideal subjects for a magazine profile—stems from their genuine pursuit of truth.

And ultimately, what lends The French Dispatch its surprising resonance is the dispatch itself. Anderson has described the film as a valentine to The New Yorker, but in my eyes it operates as an ode to the elaborate process of movie-making. “Let’s write it together,” Wright’s character says of Howitzer’s obituary, and the picture seizes on that spirit of creative collaboration. Anderson may be a fearsome auteur, but he is also a generous and humane director, which may explain why he’s built such an impressive repertory of talented actors, and why the entire cast—newcomers Elisabeth Moss and Christoph Waltz join his regulars, who also include Schwartzman, Bob Balaban, and Willem Dafoe—appears so at ease within his rigorously controlled cinemaverse.

That method of effortless acquittal—of quietly bringing natural humanity to artificial constructions—is a tenet of Anderson’s work. According to the French Dispatch staff, before his death, Howitzer favored a particular nugget of journalistic wisdom: “Try to make it sound like you wrote it that way on purpose.” Good advice. But of course, there is nothing accidental in Wes Anderson’s movies—not in the immaculately arranged frames, not in the whimsical dialogue and colorful costumes, and certainly not in the ripples of melancholy that bubble beneath the smooth surface as he gracefully transports you, yet again, to another beautiful and fantastical world.

Dune grade: B

The French Dispatch grade: A-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.