Early in his career, the writer-director Jeff Nichols developed a reputation for making movies that felt unlike the work of anyone else. The paranoid thriller Take Shelter, the noirish coming-of-age story Mud, the science-fiction parable Midnight Special—none of these was exceptional, but they all toyed with genre expectations in a manner that made them feel gratifyingly unusual. That changed with Loving, a well-intentioned docudrama that was tender, intelligent, and disappointingly ordinary. Nichols’ latest picture, The Bikeriders, continues this regression toward normalcy in a peculiar way, less by occupying a familiar template than by imitating a specific filmmaker—namely, Martin Scorsese. This movie could easily have been called “Goodfellas: Easy Rider edition.”

There are worse touchstones to copy. Cinematically speaking, The Bikeriders may not venture too far off road, but it at least zooms forward with confidence and texture. It also acquires a sense of melancholy—an elegiac wistfulness—that is both genuinely touching and somewhat dubious.

If The Bikeriders envisions its titular brawlers as manly men who never talk about their feelings (they would rather get into knife-fights than go to therapy), its script does the opposite, regularly underlining its themes with a bluntness that vacillates between clumsy and efficient. Nichols’ screenplay, which is based on the book by photographer Danny Lyon, creates a Goodfellas-esque framing device, in which the moll Kathy (Jodie Comer) narrates the events in the context of interviews with Lyon (played by a scraggly Mike Faist). There’s no real reason for this conceit beyond giving more screen time to the talented Comer, who gets to show off her flashy Chicago accent; Kathy is good company, but she’s also a passive observer in a story dominated by the countercultural hooligans whom she fears and loves.

Of which there are really only two worth mentioning, despite Nichols rounding out the cast with convincing character actors like Damon Herriman and Boyd Holbrook. The first is Benny, the very picture of bad-boy glamour, incarnated with casual magnetism by Austin Butler. When Kathy first sees Benny, he’s shooting pool, in the kind of take-your-breath-away reveal shot that admires his rippling biceps and wavy blond hair. He’s the strong, silent type, and he woos her with a very 1960s version of courtly persistence: one night of him leaning against his parked Harley outside her house (enraging her emasculated boyfriend in the process) is all it takes for their hushed introductions to turn into vows of matrimony.

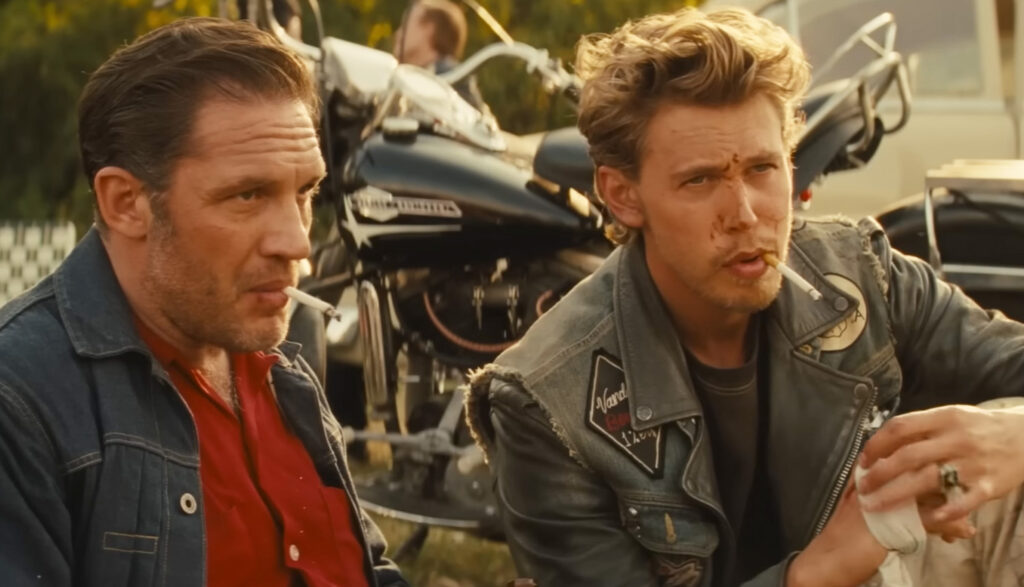

The other significant figure in Kathy’s orbit is Johnny (Tom Hardy), the de facto president of Benny’s motorcycle outfit known as the Vandals. The Bikeriders posits itself as a quasi-love triangle, with Kathy and Johnny competing for Benny’s attention. But it’s the relationship between the two men that forms the movie’s true dramatic axis, both for the characters’ clashing personalities and the actors’ stylistic approaches.

In some ways, Johnny is even more soft-spoken than Benny, given that he mumbles most of his dialogue (did I mention that he’s played by Tom Hardy?). But while they share a deep-seated loyalty to the Vandals, their temperaments differ. Benny is your prototypical hothead: brash, defensive, all too eager to get into a scrap. Butler embodies the part’s charisma effortlessly—perhaps too effortlessly. In Dune 2, he exhibited an ability to size up and meet the maximalist scale of the material; here, he commensurately attempts to tamp down his star power and coast on his matinee-idol looks. It’s effective but not quite powerful, at least until the movie’s lovely final scenes allow him to show some range.

As compared to Benny, Johnny is somehow both more wild and more restrained. He’s unconquerable in a fight thanks to sheer force of will; when a gigantic subordinate (Happy Anderson) challenges him for supremacy of the Vandals, he bites the poor sap’s leg and breaks his finger before shaking his hand. But he is nevertheless a family man who views bike-riding less as a way of life than a leisure activity, a convenient excuse to hang out with his pals; in fact, he was inspired to found the club after watching Marlon Brando in The Wild One. (“What are you rebelling against?” “Whaddya got?”) Hardy can be a showman, but he is likewise a master of understatement, and his clenched portrayal emphasizes Johnny’s coiled intensity while also lending him a quiet dignity.

The plot that surrounds these two taciturn ruffians is pleasant, predictable, and not all that interesting. As with any cinematic gang or band or company, the Vandals rise and they fall, relishing the good times before suffering the consequences of pride and overreach. This parabolic trajectory (and Kathy’s voiceover) obviously recalls Goodfellas, only the third-act accumulation of dead bodies isn’t presented in a dazzling montage set to “Layla.”

Speaking of which, while it’s unfair to demand Scorsesian levels of craft, The Bikeriders might have been more arresting if Nichols had imprinted it with a greater degree of visual panache. He does supply a few memorable images, such as the shot of Benny roaring down the open road in his motorcycle, wind whipping his hair as “I Feel Free” blares on the soundtrack (Clapton, again!). For the most part, though, his style is workmanlike, making room for soulful performances but rarely enlivening the proceedings with any zip.

Perhaps Nichols didn’t want to distract from the film’s central theme, which gradually emerges as a curious, potentially pernicious form of nostalgia. “It was the golden age of bike-riding,” Kathy tells us, and rhetoric like that tends to raise my hackles, given its propensity to fabricate a mythical yesteryear as distinct from the unhappy now. But Nichols resists crude hyperbole, even as he invisibly nudges The Bikeriders toward melodrama, one in which his heroes’ laissez-faire camaraderie is challenged by the inexorable encroachment of modernity. This latter force is personified by The Kid (Toby Wallace), a cocky upstart who contests Johnny’s laidback rule, and who perceives the Vandals not as a fraternal organization but as a potential vehicle for vice and criminality.

A different movie might have seized on the conflict between Johnny and The Kid as an opportunity for visceral excitement, but here it plays out with a simple inevitability that proves both fitting and, surprisingly, quite sad. What lingers from The Bikeriders is its sense of loss—not in terms of epochal symbols (the gleaming chrome, the leather jackets), but the disintegration of community. In the film’s most startling scene, a low-level Vandal (Michael Shannon, Nichols’ regular muse) delivers a funny, rambling, oddly beautiful monologue about how he once sought to join the army but was rejected on account of his “undesirable character.” It’s affecting not just because of his embittered anger, but because his fellows around the campfire listen to him with quiet compassion.

And that, ultimately, is what The Bikeriders is about. It may be a persuasive period piece, even if its panorama of toughs greasing engines and trading punches doesn’t represent my preferred version of masculinity. But it also recognizes the enduring importance of friendship. Its golden age may be bygone; its need to belong is at home in any era, including our own.

Grade: B

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.

A sensitive and thoughtful review, Jeremy. I’m old enough to have grown up riding motorcycles just about 5 years after the era of the movie, so the gangs, including the Outlaws, were on their downhill slide and even at the time the sense of loss was palpable. I purchased Danny Lyon’s book when it was first published in 1968 and it has stayed with me to this day. – Peter

Thanks very much, Peter, and appreciate your informed perspective. Sounds like the movie paid appropriate tribute to the era and to Lyon’s work.