Can Kevin Costner save the movies? He’s certainly willing to try, even if nobody asked him. Horizon: An American Saga is many things—an epic western, a romantic melodrama, a historical reckoning, an ode to classical masculinity—but above all, it is a wager on the sanctity of the theatrical experience. In the 34 years since Costner captured the hearts of viewers (and Oscar voters) with Dances with Wolves, the landscape of American cinema has changed, with much adult-oriented prestige fare migrating from the expansive frontier of the multiplex to the cozier confines of your living room. Costner himself has played a small part in this, having spent five seasons starring on the wildly popular TV series Yellowstone. With Horizon—which Costner not only wrote (with Jon Baird) and directed, but also financed with $38 million of his own money—he aims to unfurl a long-gestating passion project that restores the big screen to its former glory.

So the bitter and abiding irony of Chapter 1, the first of at least four planned installments in the saga (with the second slated for release on August 16 er, we’ll get back to you on that), is that it feels very much like an episode of television. It introduces a large number of characters and sketches out their preliminary circumstances, rarely affording them anything resembling closure. It also cuts across numerous locations, hinting at a potential intersection of disparate subplots but reserving any such linkage for a subsequent entry. And it concludes not with an exclamation point but with an ellipsis—a frenetic, fairly absorbing montage that comprises footage from the already-shot Chapter 2, a technique akin to the “This season on [X]” stingers that wrap up the premiere of your favorite Netflix or Amazon series. This isn’t a movie; this is a pilot.

Perhaps that’s unfair. After all, modern cinema is no stranger to sequential storytelling; hell, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, which until recently was the most dominant cultural force on the planet, essentially operated as a perpetual sequel machine, with each film functioning as a lead-in to the next (which it invariably teased via tantalizing post-credits scenes). James Cameron’s first Avatar follow-up was shot back-to-back with its second, and the Wachowskis did the same with the first two Matrix sequels. If this approach is good enough for superheroes and blue-skinned warriors and sunglassed messiahs, why can’t it work for gunslingers?

Maybe it would, if Horizon were constructed with greater clarity or energy. But while Costner does deliver a handful of engaging sequences—a slow-simmering shootout here, a game of chicken in a saloon there—his work is also indicative of a man who hasn’t directed a feature in a very long time. (This is his fourth venture behind the camera, and his first since Open Range in 2003.) The result is an odd and poky picture, one with noble intentions but spotty execution.

The sheer vastness of Horizon’s narrative can be disorienting, but with time three distinct storylines emerge. The first takes place at the titular settlement, which is raided by Apache natives in a bloody, chaotic massacre whose brutality inspires an appetite for vengeance among the surviving white residents. The second follows Ellen (Jena Malone), a fugitive from Montana who, after blasting her husband with a shotgun—the reasons for this catalyzing act of violence are unclear, but a hint of spousal abuse is implied—hides out in Wyoming, where she’s pursued by the wounded man’s two brutish sons (Jon Beavers and Jamie Campbell Bower). (The ruthless matriarch who tasks her kin with capturing Ellen is naturally played by the great Dale Dickey.) And the third shifts the action to the Santa Fe Trail, where a wagon train slowly winds its way west; it’s shepherded by a beleaguered captain (Luke Wilson), whose salt-of-the-earth sensibility chafes against the patrician superiority of a British couple (Ella Hunt and Tom Payne).

The only one of these mini-arcs that remotely works as a piece of semi-coherent drama is the Wyoming passage. That, as it happens, is where Costner himself shows up, although—in a gesture that constitutes either humility or hubris—he waits for over an hour to reveal himself. He plays Hayes Ellison, an archetypal cowboy armed with a revolver, a fedora, and a very fine mustache. We don’t learn much about Hayes over the course of Chapter 1; mostly he just wants to get laid, which accounts for his flirtations with a persistent sex worker (Abbey Lee) who also serves as Ellen’s boarder and part-time nanny. But the sequence in which Hayes traipses toward Ellen’s cabin, unwillingly unaccompanied by a greasy stranger whose manner vacillates between ingratiating and threatening, is one of the rare moments when Horizon acquires genuine suspense.

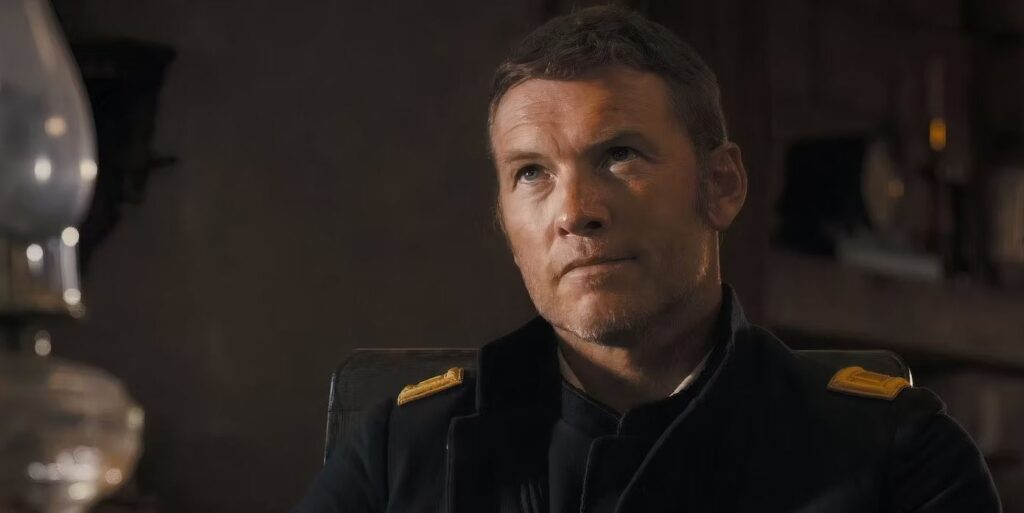

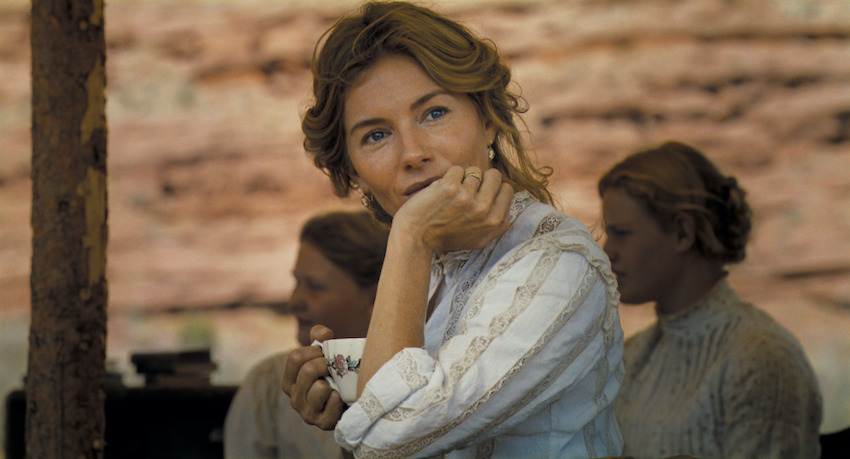

The same can’t be said for the material at Horizon itself, which is too muddled and hectic to be invigorating. That aforementioned Apache raid is the movie’s biggest and loudest set piece, but Costner’s choreography is too illegible for it to develop the desired terror; the only moment of tension occurs when a woman (Sienna Miller) and her daughter crawl under a house’s foundation and frantically try to open an airway before they suffocate. Four years later, that widow strikes up a tentative relationship with an army lieutenant (Sam Worthington); their romance is sweet and chaste, but like everything else in the picture, it’s too thinly conceived to generate any emotional power. It’s at least better defined than the caravan scenes, which play out as pure prelude, hinting at a potential conflict that for now remains wholly theoretical.

Such speculation is basically the film’s entire vibe, but tonally speaking, Horizon is a curious creature. Costner plainly wants to evoke the full breadth of manifest destiny—how it mingled hope and horror, advancement and regression, civilization and annihilation. To that end, he includes a lengthy scene of internal squabbling within an Apache tribe, where a youthful firebrand (Owen Crow Shoe) agitates for combat while a more reserved elder (Gregory Cruz) counsels diplomacy. As for the colonizers, they run the prejudicial gamut; Worthington’s officer warns that seeking retribution against the native population (he even uses the politically correct term “indigenous”) will only produce further slaughter, others reject his caution and instead form a bloodthirsty war party, and in between lies a pragmatist (Scott Haze) who opines that this cycle of violence is simply an ingrained fact of human nature, even as he takes pains—in the movie’s second-best scene—to prevent a murder at a trading post. This all possesses the veneer of sensitivity without real substance, as though Costner is acknowledging the period’s endemic bigotry without exploring it.

More at the forefront of his mind, it seems, is his portrait of the era’s masculinity. Early on we see a teenage boy spurn his mother’s invitation to dance at a soirée; when his parents’ home is attacked that evening, he turns down the chance to escape, preferring to stay and fight with his father while the women hide and tremble. Meanwhile, that English husband on the trail, with his books and spectacles, is the epitome of effeminate weakness; he can’t even help repair a broken wheel, and his impotence consternates Wilson’s rugged leader. And of course, Hayes himself is the strong, silent type—a real man’s man who’s quick on the draw and stout between the sheets. Horizon feels too colossal, both narratively and conceptually, to be dismissed as retrograde, but if Costner intends to truly interrogate the mythology of manhood in the old west, he’s saving that for a future installment.

And that, again, is the ultimate sensation the movie imparts: the feeling of delayed gratification. (The closing credits give amusingly high billing to Giovanni Ribisi, who literally doesn’t appear in the film until its final seconds.) If you want to experience the payoff of its protracted setup, well, you’ll just need to show up for Chapter 2.

Assuming you can find it, that is. Horizon’s immediate sequel was scheduled to arrive on August 16, but two days ago, news broke that the studio had yanked it from the theatrical calendar, purportedly to build greater word of mouth regarding Chapter 1 via—wait for it—streaming. I reacted to this announcement with mild horror; as much as I found this first episode frustratingly incomplete, it’s also sufficiently ambitious and appealing to make me intrigued for a follow-up. At the same time, the decision seems weirdly fitting. For all its impressive scale and strenuous effort, this undeniably big movie proves best suited for the small screen.

Grade: C+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.