It’s fashionable to judge horror movies based on how scary they are. It’s a fair albeit reductive question; if comedies are supposed to make you laugh and tearjerkers are designed to make you cry, then a good fright flick should presumably make you catch your breath and clutch your armrests. By this measure, Longlegs, the fourth feature from writer-director Osgood Perkins, is moderately successful; it’s a thoroughly unsettling experience, even if it’s unlikely to have you covering your eyes in abject terror. But in terms of cinematic construction—its building of mood, its manufacture of tension, its rattling spookiness—Longlegs is a small-scale triumph. This may not be the scariest modern horror movie ever made, but it is surely one of the creepiest.

Conceptually speaking, this is nothing new for Perkins, whose prior pictures—the re-titled Blackcoat’s Daughter (changed from February), the annoyingly titled I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House, and the gender-flip-titled Gretel & Hansel—all cultivated an inescapable sense of doom. They felt weird and looked great (Gretel & Hansel made my Best Cinematography ballot in 2020), but they prioritized bone-chilling atmosphere over legible plotting. With Longlegs, Perkins has properly calibrated his nerve-jangling sensibility, locating the proper balance between apprehension and entertainment. He hasn’t curtailed his gift for upsetting his audience—a number of scenes here are deeply disturbing—so much as channeled it into a more propulsive story. He has his cake and taints it too.

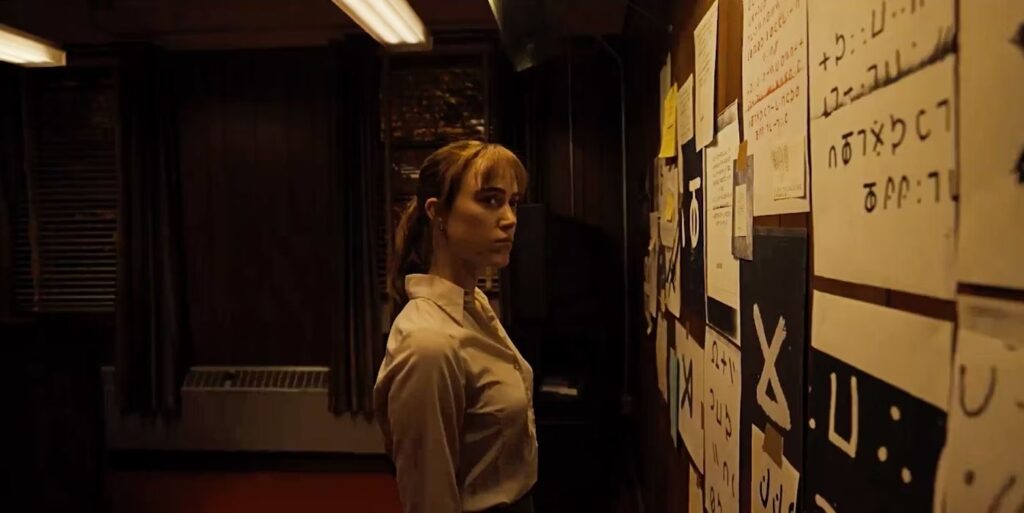

For such a perverse movie, Longlegs exhibits a surprising ability to connect with viewers on an emotional plane. Much of this derives from the simple casting of Maika Monroe, that erstwhile scream queen whose mere presence infuses the proceedings with a brittle humanity. She plays Lee Harker, a recently minted FBI agent blessed with a sharp mind and an eerie intuition. “It’s that one,” Lee says to her (very male) partner as they’re canvassing a suburban street, searching for a perpetrator who might be lurking in any random house. How could she know? “It’s like something tapping me on the shoulder, telling me where to look,” she later explains to her boss, Carter (a steady Blair Underwood). Perkins wisely doesn’t delve too deeply into Lee’s apparently paranormal abilities—in a nice touch, when participating in an absurd number-guessing exercise meant to gauge her deductive talents, she chooses wrong roughly half the time—and neither does Carter; he cares more about results than process, and he has bigger, more diabolical fish to fry.

That would be the titular murderer, a gangly, chalk-white monster played with characteristically gonzo energy by Nicolas Cage. When we first see Longlegs, we don’t really see him; instead, the movie’s chilling opening scene unfurls from the vantage of a young girl, meaning the man towering over her is only visible from the mouth down. It’s a smashing introduction that instantly reinforces Perkins’ facility with forced perspective; his framing is always purposeful, compelling you to perpetually scan the background in fear, as though a demonic figure might emerge at any moment. He also likes toying with aspect ratio; most of the film unfolds in widescreen and is set in the mid-’90s (we know this thanks to the large framed photo of Bill Clinton on Carter’s office wall), but a handful of ’70s flashbacks are shot in a squarish, claustrophobic box, so when that cold open abruptly transitions to a ruby-red title sequence, the color gradually stretches outward, like blood spilling across the screen. (Perkins later repeats this trick when a pivotal flashback to Lee’s youth concludes with the camera finding the adult agent in her childhood bed; that expanding boundary is just as disquieting the second time.)

With Longlegs, Perkins has marshaled his skills for agitation and discomfort in service of a plot that is, in its bold strokes, curiously familiar. A brilliant but green female FBI agent, eager to prove herself but haunted by a preadolescent trauma, partnering with a stoic but supportive male mentor in the desperate chase to track down a pitiless serial killer—this is essentially the logline for The Silence of the Lambs. The movie’s broad trajectory mimics other celebrated police procedurals as well; Lee’s decoding of Longlegs’ cryptic letters evokes Zodiac, while her preternatural instincts recall the tortured hero of Manhunter.

Yet even if Longlegs’ descriptive skeleton may be creaky, its artistic flesh is entirely its own. Combining arrhythmic editing with formal elegance, Perkins creates a miasma of suffocating wrongness—the sense that things and people are somehow off. This is most obvious during an archetypal scene where Lee visits that classic horror-exposition factory, the psychiatric ward—only instead of discovering plot points, she finds herself on the receiving end of matter-of-fact, cold-blooded malice spewed by a creepily composed patient (Kiernan Shipka, who starred in The Blackcoat’s Daughter). It’s also present in the phone calls between Lee and her mother (Alicia Witt), which play out with an oddly stilted politeness, and in basic objects, like the hand-crafted porcelain doll that suddenly open its eyes, giving both you and Carter an all-time shock. Under Perkins’ stewardship, even patches of inky blackness in the frame attain an elemental power, making you question whether you’re looking at a spectral figure or just staring into nothingness.

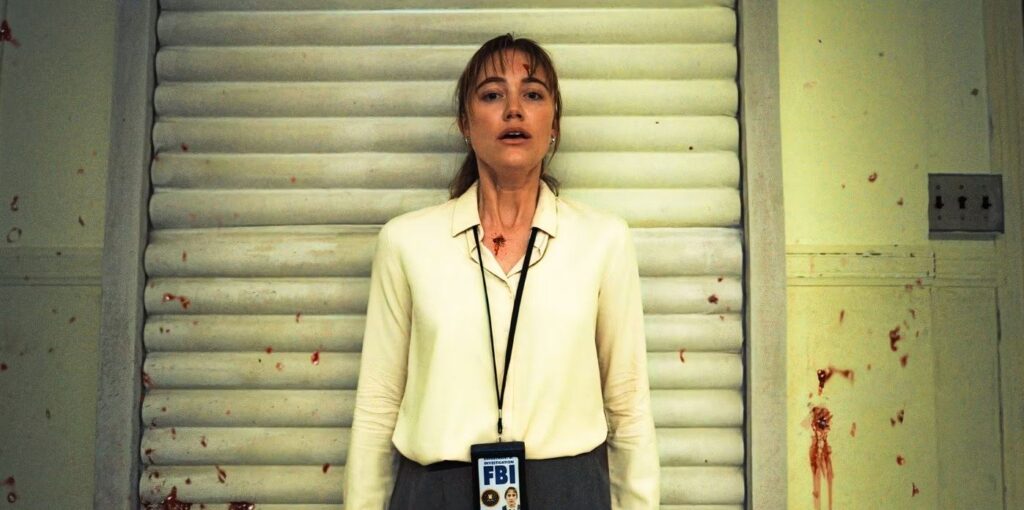

Again, such clammy manipulation is Perkins’ stock in trade, but here he tethers it to a narrative that acquires forceful, inexorable momentum. The key in this regard is Monroe. Lee is a potentially clichéd character (think Clarice Starling with a sixth sense), but Monroe imbues her with a fully rounded personality—sparky intelligence, rugged persistence, solemn decency—that makes her intensely sympathetic. The upshot is that even as Perkins is constantly freaking you out, Monroe draws you in. Her coiled restraint also operates in engaging stylistic counterpoint with Cage, who rises up to meet his larger-than-life villain, spiking his usual syncopated lunacy with a dash of genuine menace. The scene where Lee finally comes face to face with Longlegs doesn’t feature much in the way of physical threats, but it nonetheless throbs with incalculable terror.

Inevitably, that spine-tingling dread dissipates somewhat as Longlegs hurtles toward its conclusion, which is well-staged but which still must grapple with the banality of supernatural mayhem. (It is here where I’m obligated to point out that the best horror film of the new century remains the Monroe-starring It Follows, in part for how it miraculously sustains its oppressive tension through its climax.) As a metaphor, the picture suggests a bundle of potentially intriguing ideas—about the pulls and pitfalls of religious fundamentalism (as in The Blackcoat’s Daughter, characters repeatedly proclaim “Hail, Satan!”), about the sins parents visit upon their children in the name of protecting them, about how men should maybe listen to women every once in a while—but they never coalesce into a coherent theme. The movie is too pervasively creepy to be intellectually stimulating.

Which is more compliment than criticism. Longlegs is too busy amping up the suspense and fueling your nightmares to bother with provocative subtext. Perkins’ merciless technique might not make you fear for your soul, but you may want to say a fruitless prayer for your nerves.

Grade: B+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.