Today in the Manifesto’s Review of 2013, we’re continuing with our look at the year’s failures. If you missed Part I, you can find it here.

The Lone Ranger. I concede that The Lone Ranger is not a good movie. Tonally, it lurches between lifeless comedy and nostalgic neo-Western. The writing is both winkingly self-conscious and painfully earnest, but the jokes are dead on arrival, and the odes to the grandeur of the Old West feel strained and unconvincing. The typically reliable Johnny Depp seems unsure of how much humor he’s supposed to bring to his character, an uncertainty that applies equally to the film’s weird flashback structure. And the plot is both overstuffed and undercooked. It’s a mess.

But God bless him, Gore Verbinski knows how to stage an action sequence. As a modern moviegoer, I have grown tired of virtually all “high-octane” action scenes in would-be blockbusters. They’re invariably loud, long, and incoherent, confusing entertainment with spectacle; in their giddy embrace of CGI’s infinite possibility, action directors relentlessly assault audiences with explosions and rapid cutting while ignoring filmmaking fundamentals like blocking and framing. (For a particularly egregious example, see the first film highlighted here.) Verbinski, who helmed the first three (excellent) Pirates of the Caribbean pictures and the wonderfully bizarre Rango, is different. He puts a premium on balletic choreography, and certain moments in The Lone Ranger—especially when multiple characters are pursuing speeding trains from various angles—are downright symphonic in their fluidity and integration. And so while The Lone Ranger may be a disaster, it’s also oddly promising because it reinforces Verbinski as an undeniably talented and energetic filmmaker. If he would only invest a fraction of that energy into minor matters such as plot, dialogue, and character, he’ll get back on track.

Lore. There’s considerable potential buried within Lore, and quite a bit of talent visible on the surface as well. The potential lies in the premise, which follows the eldest daughter of a pair of high-ranking Nazis who, after her parents shuffle off to face the music (and perhaps a firing squad), must shepherd her younger siblings in a trek across Germany. And the talent derives from the title character herself, played with extraordinary poise and hidden anguish by Saskia Rosendahl. But Australian director Cate Shortland squanders this promise in a misguided effort to craft a quixotic meditation on family and identity. Or something like that. In truth, I’m not quite sure what Shortland is trying to accomplish with Lore. I just know that she stubbornly refuses to inject any energy into her proceedings. Lore features elements of many genres—it perhaps could have been, in different hands, either a chilling horror movie or a searching character study—but Shortland muddles these elements, resulting in a vague, shapeless picture that occasionally tantalizes but rarely coheres. Certain scenes spark with intrigue, but for the most part Shortland is more interested in evoking a mood than telling a story, rendering a late reveal regarding a critical character’s identity forced and false. Lore is by no means a bad movie, but Shortland’s deliberate approach feels less contemplative than tentative. As a result, Lore slows when it should quicken, stammers when it should enunciate, and—unlike the American military presence that hovers on the movie’s periphery—hesitates when it should charge.

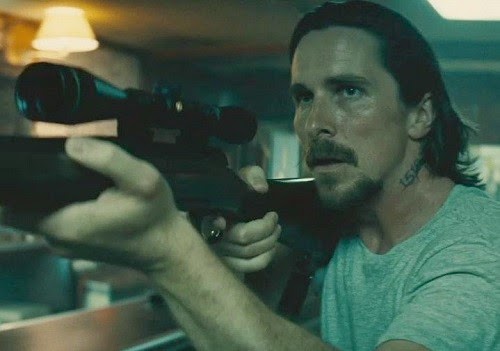

Out of the Furnace. If there’s one thing you learn watching Out of the Furnace, it’s that Scott Cooper is a fan of The Deer Hunter. Set convincingly in a dreary Appalachian town—the kind where the steel mill is forever belching smog and the locals are always either fighting or drinking—this crime fable plays like a paean Michael Cimino’s Oscar-winning opus, right down to the protagonist sizing up a target with his rifle and debating whether to pull the trigger. But while Out of the Furnace effectively captures The Deer Hunter‘s singular tone—it unfolds in a decidedly uneasy Middle America, where hardscrabble decency mingles with perpetual discontent—it’s also proof that evocative atmosphere can only carry a thin story so far. And Cooper’s screenplay, which he co-wrote with Brad Ingelsby, is just plain starved. The movie’s hero, a frustratingly virtuous ex-con (imbued with typical, which is to say staggering, authenticity by Christian Bale), just wants to live honorably, but that honor compels him to exact vengeance after his brother (Casey Affleck, chiseled and impressive) falls victim to the misdeeds of a repugnant gangster (Woody Harrelson, holding nothing back). (The film’s opening scene, in which Harrelson’s heavy sexually assaults a woman, then nearly beats a man to death for interfering, clues you in to the degree of subtlety Cooper wields in his characterizations.) And that’s pretty much it. Guns are fired, punches are thrown, and righteousness wins out, or so Cooper would have you believe. He wants you to think that you’ve borne witness to a profound morality play. But Out of the Furnace is far too simplistic—and too dull—to impart any sort of lesson, other than perhaps that if you witness a brute terrorizing his date at the local drive-in, keep your mouth shut.

Reality. Matteo Garrone’s Gomorrah was widely hailed as a masterpiece, undercutting traditional mob-movie romanticism with harsh realism and miasmic suffering. It left me a bit cold, partly because it divided its time across too many vaguely sketched characters, but primarily because Garrone’s insistent refusal to sentimentalize his gangsters felt arch and studious, robbing his ostensibly dire proceedings of urgency or even interest. With Reality, Garrone solves one of these problems: He focuses his film entirely on a downtrodden fishmonger (played brilliantly by Aniello Arena) who becomes obsessed with the prospect of appearing as a contestant on Italy’s version of Big Brother. But the heightened intellectual approach persists, and Garrone seems so intent on chronicling his protagonist’s descent into madness with detachment that the movie feels less insightful than merely labored. Several critics have interpreted Reality as a satire of organized religion—our fishmonger has absolute faith that he’s destined to appear on the show, despite no visible evidence—but Garrone’s aloof style blunts any satirical impact. Indeed, the movie seems opposed to delivering any impact, preferring quiet observation over actual storytelling. Reality is redeemed somewhat by Arena’s extraordinary performance; he’s completely convincing as a man who’s capable of interpreting the most mundane events as signs from his producer gods. But he’s a bright vessel toiling in a dark, listless film, one that mistakes indifference for intelligence. Garrone’s resistance of formula may be laudable in theory, but on the screen, Reality could have used a dose of artifice.

Saving Mr. Banks. At an elemental level, there’s much to enjoy in Saving Mr. Banks, John Lee Hancock’s overwrought, sap-stricken depiction of the battle over the film rights to Mary Poppins. Emma Thompson is her usual sharp self as author P.L. Travers, and the “making of” conceit lends itself so naturally to light, pleasurable filmmaking that even Hancock’s grandiose tendencies can’t sabotage it. To that end, most of the scenes set in 1960s Los Angeles—in which Travers bickers contentiously with a much-harried writing staff (Bradley Whitford, B.J. Novak, and Jason Schwartzman, all good) and their playful, persistent overlord, Walt Disney (Tom Hanks, dangerously relaxed)—are airy and enjoyable.

But that isn’t enough for Hancock, the director of the equally mawkish The Blind Side. No, Travers must be haunted by flashbacks to her Australian childhood in which her alcoholic father (a wonderful Colin Farrell, who flings himself into the part) wages war with his own allegorical demons. The existence of backstory itself isn’t a cinematic sin, but Hancock inexplicably spends nearly half of Saving Mr. Banks‘ swollen runtime in the distant past, tirelessly scrounging for emotional clues to the adult Travers’ prickly obstinacy, then spoon-feeding them to his audience. It’s a catastrophic miscalculation, one that torpedoes an enjoyable picture and saddles it with sentimental drivel. Near the end of Saving Mr. Banks, there’s a critical scene in which a bushel of pears roll portentously across a dusty floor, their motion presumably freighted with significance. To Hancock’s credit, the moment indeed elicits a powerful response; to his detriment, I doubt guffaws are what he had in mind.

Shadow Dancer. Shadow Dancer is a deeply promising film, one haunted by sadness and tinged with regret. It exhibits a strong sense of place—you can practically feel the Irish chill seep into your bones—and it features a breakout performance from Andrea Riseborough, a terrific and emerging actress on whom I’ll continue to heap praise as the Manifesto’s review of 2013 progresses. Riseborough is so good at conveying steely resolve and submerged longing that you’re almost willing to forgive Shadow Dancer for its fundamental shortcomings, namely its languid pacing, muddled storytelling, and thinly sketched supporting characters.

But those shortcomings are present, largely because James Marsh (who also directed the middle installment of the excellent Red Riding trilogy) never fully commits to his espionage plot, in which Riseborough’s IRA firebrand agrees to do the bidding of an MI-5 agent (Clive Owen, steady) in order to protect her son. There’s potential there, and if Marsh were as dedicated to careful plotting as he were to building an atmosphere of oppressive dread, Shadow Dancer could have proved to be a powerful fusion of slow-burning thriller and thoughtful character study. But even as allegiances continuously shift and murders pile up, the film’s story never coheres, and as convincingly as Riseborough evokes her character’s utter despair, we’re left confused rather than dismayed. Shadow Dancer is ostensibly a movie about searching—for criminality, for love, for peace of mind—but ultimately, it’s just a stunning performance in search of a movie.

Trance. The cool thing about a movie like Trance, Danny Boyle’s mind-bending thriller, is that anything can happen. But that creative freedom also proves to be the film’s undoing. Trance takes place in a gleefully illogical movie-verse, one in which flashbacks abound, plot points fold in on themselves, and dream sequences blur into reality. (At one point, the top half of Vincent Cassel’s head gets sliced off, which only seems to make him angry.) It’s pulpy nonsense, which makes it a natural fit for Boyle, a director who’s never needed much goading to jump into the deep end (remember that baby scene in Trainspotting?). And for a time (and with the help of Rick Smith’s terrific score), it’s easy to immerse yourself in Boyle’s frenetic, hyperactive world of sensory overload, one that eagerly explores a variety of alluring genre elements: hypnosis, stolen art, honor among thieves, Rosario Dawson’s body. But navigating Trance‘s constant fakeouts, double-crosses, and narrative figure-eights eventually grows wearisome, and as Boyle keeps firing neon curveballs at you, it becomes increasingly clear that he’s less a magician than a charlatan. He’ll show you what looks to be a diamond, and on its surface, Trance is an impressively glitzy piece of work. But give it one poke with a well-aimed hammer, and it turns to dust.

Next time out: The Intriguers.

Previously in the Manifesto’s Review of 2013

The Failures (Part I)

The Unmemorables (Part II)

The Unmemorables (Part I)

The Worst Movies of 2013

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.