During one of the best scenes in Alien: Covenant, a robot tells an antiquated model of himself why he was ultimately decommissioned. “You were too human,” the current version bluntly informs his predecessor. “Too idiosyncratic.” The explanation makes sense—the older model’s uncannily lifelike behavior unsettled his mortal masters—but it carries with it an undeniable sting of irony. Covenant, the sixth entry in the Alien franchise and the third directed by Ridley Scott, is a vigorous and impressive piece of mass-market entertainment, a finely calibrated horror film that boasts expert effects work and pulse-pounding set pieces. Yet it is also clearly the product of corporate assembly, a sequel to a prequel that ably perpetuates the series’ mythology but does so with minimal distinction or ingenuity. It’s a bit like that newly updated cyborg who lectures his elder counterpart: sleek and efficient, but not idiosyncratic enough.

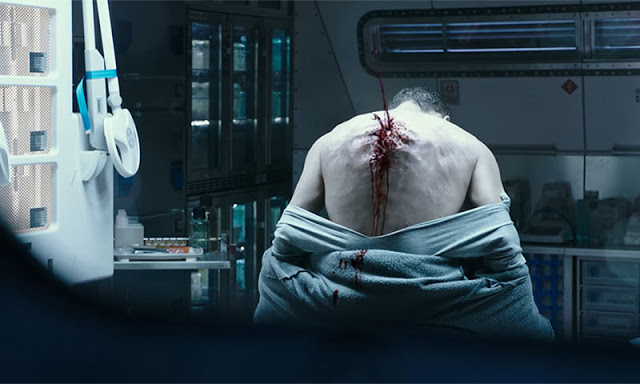

Or maybe I’ve just seen too many Alien movies. If you haven’t watched Scott’s classic original (which is slightly overrated, but that’s a different discussion), you are likely to be gobsmacked by the spectacle of violent death and physical suffering that the director has arrayed before you. Setting aside Sigourney Weaver’s spunky and sexy performance, Alien achieved cinematic immortality for two reasons: its historically great tagline, and John Hurt’s upset stomach. Seeing as Covenant cannot hope to match the former (though “The path to paradise begins in hell” isn’t half-bad), it strives to one-up the latter. Throughout this movie, nasty critters burst out from within the insides of unsuspecting human hosts, spilling blood and splintering backbone in the process. Alien enthusiasts may have seen this before, but they likely haven’t seen it this excruciating and visceral.

They will certainly recognize and appreciate Scott’s patience. After all, the laws of horror require a tense, twitchy buildup before chaos is unleashed. Following a sharp and ominous prologue set in a dazzling mountainside utopia, Alien: Covenant opens in that vast void where no one can hear you scream, its titular vessel crawling through inky black space. Though the ship is carrying thousands of hibernating colonists and embryos, the only conscious soul on board is Walter (Michael Fassbender, typically fantastic), a newfangled “synthetic” who acts as something of a caretaker to the dozen or so crew members suspended in cryosleep. Despite Walter’s best efforts, something goes boom, rattling the crew from their slumber (and recalling last year’s unduly maligned anti-romance Passengers). When they wake, they elect to change course to a nearby planet that appears to be habitable and that is emitting a mysterious radio transmission. When a subordinate questions the wisdom of this decision, the acting captain waives her off—when has a little friendly exploration of an uncharted territory ever gone wrong?

What follows is predictable, though it is not unpleasant. As the crew split up and trudge across the planet’s surface, looking for signs of life and marveling at this new world’s natural beauty (filming took place in New Zealand), they inadvertently activate dormant alien spores, which swiftly and silently invade a pair of human bodies. (In a superbly creepy touch that will have you racing to the store for Q-tips, one set of spores enters via the ear canal.) At this point, the fate of these two oblivious incubators is assured—the spores will gradually grow into merciless animals who don’t like being confined inside a human rib cage—but Scott still charges the inevitable bloodshed with excitement, adding some gravitas to go with the gore. In the movie’s most suspenseful sequence, the Covenant’s biologist finds herself trapped in a medical bay with a colleague who’s falling prey to the alien’s signature chest-bursting move; as she clamors to be released, a third officer looks on pityingly from the other side of a sealed doorway, racked with guilt and paralyzed with fear.

She isn’t the only one. Before long, quite a few crew members are dead, though it’s difficult to mourn them too heavily—most of the human characters in Alien: Covenant are indistinguishable, or they would be if they weren’t played by recognizable actors. The few who do stand out include Daniels (Katherine Waterston, suitably terrified), the second-in-command with a keen sense of trepidation; Tennessee (Danny McBride, not awful), a cocksure pilot with a cowboy hat; and Faris (Amy Seimetz, very good), another pilot who’s also Tennessee’s wife. There are quite a few other spouses in the picture—in a clunky bit of hand-holding, officers constantly refer in the third person to “my wife”, just to underline the marital bonds tying various crew members together. Perhaps screenwriters John Logan and Dante Harper thought this device would intensify the characters’ emotional plight, but it only reinforces their pervasive sameness, as it’s difficult to tell which wife (or husband) is which.

Yet just when Alien: Covenant threatens to descend into gruesome monotony, it flares to vibrant life upon the arrival of a mysterious, hooded figure. Is it the last Jedi? No, but there is nevertheless an aura of mysticism, even a touch of the supernatural, about the robed warrior who suddenly rescues the crew from a pair of ravenous aliens. When he lowers his cowl, however, he is revealed to be a familiar face—namely, Walter’s. Yet he is not Walter but David, the sentient android who caused so much trouble for Noomi Rapace and her cohorts in Prometheus. He ended that film with his head severed from his body, yet here he stands, quite well, if not strictly alive.

David, of course, is also portrayed by Fassbender, and if Alien: Covenant is largely a typical sci-fi gore-fest, it at least affords us the opportunity to watch one of the world’s great actors shape two complementary personas. With his clipped accent and stiff mannerisms, Walter is a proficient but servile assistant, a laborer who obeys orders without question. David, however, is a different creature, an avatar of patrician superiority and derision. He has an appetite for mischief, as well as a taste for the operas of Wagner. He is also something of a horticulturist, though he favors breeding aliens rather than plants. As for humans, David views the species with a mixture of curiosity and contempt, impressed with their perseverance yet scornful of their mortality. But he regards Walter—who is technically a more advanced version of himself—with fascination.

Aside from being technologically accomplished—the special effects of twin cinema have come a long way—the scenes in Alien: Covenant between David and Walter are deliciously, thrillingly weird. The tentative dance between them is opaque and ambiguous, so that it is unclear whether we are watching the prelude to a battle or the start of a courtship. A sequence where David teaches Walter how to play the flute positively throbs with unclassifiable tension, as it seems equally likely to lead to sex or murder. (With a twisted smile, David coos, “I’ll do the fingering.”) And Fassbender pours his prodigious talent into the performance(s), heightening David’s supreme arrogance while also emphasizing Walter’s robotic wariness.

It’s tempting to imagine an entire movie built around David and Walter’s queasy and beguiling relationship, but Scott has too much killing to do. In short order, he returns the film to its principal business of slime and splatter, his xenomorphs (as the aliens are called) adeptly sowing death and devastation. In so doing, he conforms to the traditions of the genre, dispatching his interchangeable victims one by one. (In this, the film is not all that different from Kong: Skull Island, a well-executed monster mash that similarly treated its humans as fodder.) There is even the age-old trope of a character breathlessly sheltering herself against a wall, then hearing something behind her and slowly turning toward the camera, eyes widening as she locates the monster perched quietly above her, coiled and ready to strike.

Again, all of this mayhem is skillfully staged. Setting some of the action on the planet’s surface allows Scott to inject some geographic variety into the carnage, such as a hectic sequence on the roof of an airborne vessel, as Daniels improbably attempts to snatch a xenomorph in the jaws of a giant crane. (Meanwhile, an early scene in which papery sails spread out from the ship to catch the light of a distant sun showcases Scott’s occasional gift for majestic imagery.) But while that aforementioned nightmare in the med bay undeniably evokes the horrors of Hurt’s demise from the first film, Alien: Covenant lacks a truly original showstopper. Certainly, there is nothing as harrowing as the moment in Prometheus where Rapace was forced to give herself an impromptu abortion, nor anything as triumphant as Weaver kicking extraterrestrial ass by way of a cargo-loader in Aliens.

Thirty-eight years ago, when speaking of the inaugural xenomorph, Ian Holm memorably intoned, “I admire its purity.” But while Alien: Covenant is a robustly entertaining horror film, it is too manufactured and familiar, too diluted by formula, to be pure. Strangely enough, I find myself sympathizing with David. He may be the film’s brilliant stealth villain, but he is also an artist, an innovator who’s invested in creating new life. Scott, in replicating some of his own greatest hits, acknowledges David’s visionary spirit but fails to honor it.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.