Today marks the long-awaited arrival of Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, an enormous blockbuster that will make gobs of money, thereby rescuing the box office from its “post-summer slump.” But just because recent releases haven’t been financially successful doesn’t mean they haven’t been interesting. This past weekend featured modest expansions of three small-scale movies that collectively scraped together less than $3 million, which is less than Wakanda Forever will earn in an hour. There’s nothing inherently venerable about independent films, but these three pictures have more in common than modest budgets; they’re also all notably personal in their storytelling, with original screenplays written by their director. If Black Panther is the antidote for Hollywood’s commercial doldrums, these movies provide a valuable reminder that contemporary cinema consists of more than franchises and superheroes.

It doesn’t get much more personal than Armageddon Time, James Gray’s autobiographical depiction of his childhood in Queens in 1980. (In this, Gray gets a jump on Steven Spielberg, whose Arizona-set self-reflection, The Fabelmans, hits select cities today and will go nationwide the day before Thanksgiving.) Gray casts the fresh-faced, soft-featured Banks Repeta (recently in The Devil All the Time and The Black Phone) in the role of young James Gray Paul Graff, an aspiring artist whose idle classroom drawings exhibit greater skill than your typical 12-year-old doodle. Maybe someday he’ll grow up to be a talented filmmaker. Who can say?

In fairness to Gray, Armageddon Time doesn’t feel overly self-indulgent. At the same time, it rarely feels like the work of an especially gifted director. I’m mixed on Gray’s record—I highly admired The Immigrant and The Lost City of Z but was left cold by We Own the Night and Ad Astra—but most of his movies at least demonstrate a forceful combination of craftsmanship and energy. Here he’s throttled down, prioritizing competence over flair. It’s a defensible approach, given the film’s focus on character rather than style, but it also renders the proceedings rather wan.

As a protagonist, Paul is less of a surrogate than a blank slate onto which Gray can project conventional coming-of-age anxieties and curiosities. (Not the pubescent kind, though; unlike many pictures of its ilk, such as Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast, Armageddon Time doesn’t clutter itself with a fledgling romance, to the point where virtually the only woman on screen is Paul’s mother, played with smart restraint by Anne Hathaway.) One of the story’s main threads involves his budding friendship with Johnny (Jaylin Webb, from Till), a slightly older Black classmate who introduces Paul to the pleasures of the Sugarhill Gang and kindles his nascent rebellious streak. Gray’s script draws a tenuous, blurry line between Paul’s Jewishness and Johnny’s Blackness, observing that both boys’ forebears are victims of discrimination but that the latter’s present circumstances are more invidious. It isn’t all that insightful, but the fuzziness is arguably part of the point, as Paul must recognize that he’s both a target of prejudice and a child of privilege.

He learns that lesson from two men of differing temperaments. His grandfather, Aaron, played with twinkling charm by Anthony Hopkins, encourages Paul’s artistic ambitions, even as he educates the lad about his Jewish heritage and chastises him for wavering in the face of bigotry. Where Aaron is mischievous and wise, Paul’s father, Irving (Jeremy Strong), is cantankerous and crude; he worries that his child is too soft for the world, and he channels that fear into beatings. Is Irving a gratifyingly complex character, or just a muddled and inconsistent one? Despite Strong’s immersive performance, Gray lets him off a little easy, as he does Paul during a crucial late sequence where the screenplay tries to valorize its hero while also making him the beneficiary of a lucky break.

If Armageddon Time’s narrative developments can seem contrived, its vibe nonetheless remains thoroughly pleasant. Gray naturally evinces a strong feel for the period—Reagan’s ascent is imminent, prompting jeers at Paul’s home and cheers at the private school where his parents desperately enroll him, and which is bankrolled by a recognizable villain (bonus points for the Jessica Chastain cameo)—along with an instinctive command for domestic crowdedness; an early dinner scene in which Paul defiantly orders takeout dumplings rather than swallow his mother’s homemade scrod buzzes with authentic familial bickering. (Additional bonus points for Tovah Feldshuh showing up as a no-nonsense granny.) The Graffs are a fun lot to be around, even if their primary role is to shepherd an anodyne youngster on his inevitable path to Hollywood.

Where Armageddon Time scrupulously recreates the time and place of the director’s youth, Aftersun supplies a more freewheeling evocation of the crucible of childhood. The flawed but deeply promising feature debut of Charlotte Wells (who’s described it as “emotionally autobiographical”), it’s less interested in reenacting pivotal episodes than in capturing the particular, peculiar sensation of a father-daughter bond. At times, it feels less like a movie than a memory, refracted through the haze of recollection and bouncing back to us in the form of scrambled thoughts and shattered dreams.

Fairly early in Aftersun, it becomes evident that its narrative will be relatively plotless, with little of substance actually happening. A very young father named Calum (Paul Mescal, forever from Normal People) is taking his 11-year-old daughter, Sophie (Frankie Corio, a born heartbreaker in her first role), on a weeklong vacation in Turkey, and that’s pretty much it. Despite a curious miasma of danger hovering in the air, there are no kidnappings or car crashes or injuries; what passes for incident here is a hotel inadvertently booking a room with just one bed. As a result, the film’s pace vacillates between deliberate and downright sluggish. But while it’s fair to accuse Wells of neglecting dramatic urgency, it’s plain that her artistic interests lie elsewhere.

Not that she’s indifferent to character. In a series of unhurried scenes which find Calum and Sophie engaging in prototypical kid-vacation behavior—visiting the arcade, playing billiards, lounging by the pool, seeing the sights (in a parallel universe where this movie is a smash hit, Turkey’s tourism industry will surely see a corresponding boom)—Wells slowly but persistently explores their relationship, gradually constructing a link that is both ironclad and brittle. Calum, all in all, is a pretty good dad; he’s gentle and supportive, protecting his daughter from the perils of the world while simultaneously nurturing her independence. He’s also something of a deadbeat, and the inherent contradiction of his parenting—his abiding decency combined with his overall lack of presence—becomes one of the movie’s primary themes. He wants to be a better father than he actually is. Sophie, played by Corio as both cherubic and wise beyond her years, seems to recognize this, even if her understanding is sometimes barbed with frustration and resentment.

Wells intensifies this fraught-but-tender dynamic by deploying a sort of aggressive naturalism. Wielding a striking and at times jarring command of cinematic trickery—mirror shots, sharp cuts, jagged montages—she toys with time and perspective, replaying scenes and repeating visual motifs. The most frequent of these is the unexplained image of Calum at a rave surrounding by strobing lights, and perhaps accompanied by a woman of unclear relation to Sophie. Is this a flashback? A glimpse of the future? A dream? The ambiguity can feel vexing as well as tantalizing; I confess that I spent a healthy chunk of Aftersun restless, anxious for its mellow mood and antic style to coalesce into something greater.

And then, how it does. Beginning with a karaoke scene in which Sophie cheerfully butchers an R.E.M. banger—the ensuing exchange between her and Calum, involving singing lessons and financial means, is devastating—the movie accumulates a startling degree of emotional momentum. It isn’t as though Wells tidily clarifies the story so much as she synchronizes its messiness with her bustling visual imagination. The simple shot of a woman placing her feet on a carpet, accompanied by murmured birthday wishes, turns into a stomach-punch, while a bravura final camera pivot seems to collapse time and space altogether.

The sheer force of Aftersun’s climax would seem to be at odds with a work of such modesty and intimacy. But Wells’ triumph, achieved with greater clarity and power than Gray’s straightforward approach, is to convey how memory can shape our experiences, and how childhood can appear so momentous when viewed in the distorted light of reminiscence. She’s hardly made a perfect movie, but she has located the beauty, and the love, in two people’s imperfections.

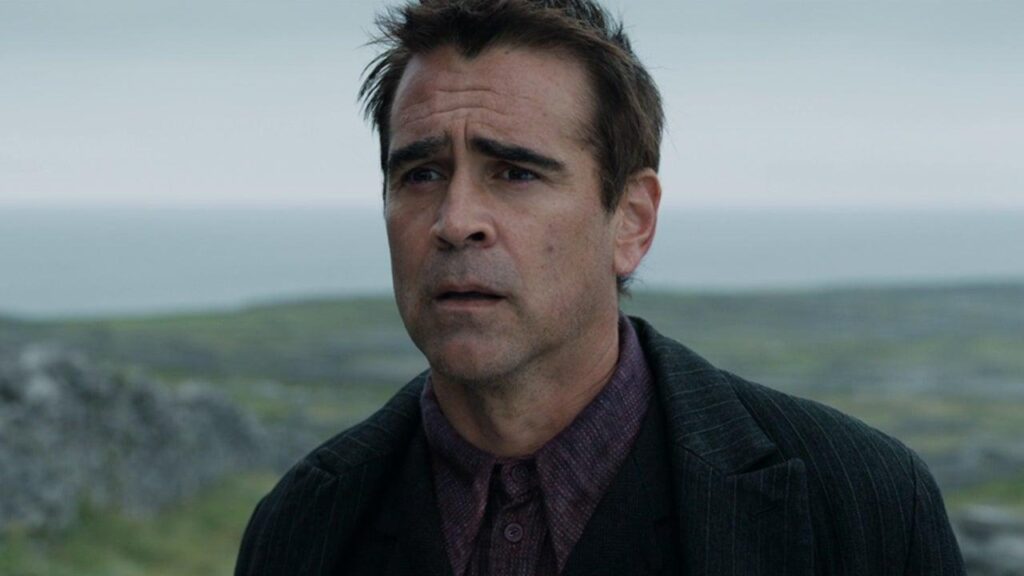

If Armageddon Time is literally autobiographical and Aftersun is emotionally autobiographical, The Banshees of Inisherin is wholly fictional, though its storytelling feels no less personal. The latest work from Martin McDonagh, it reunites In Bruges costars Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson for a meditative study of friendship, community, and vengeance. It’s less showy than McDonagh’s prior films, which also include the meta crime thriller Seven Psychopaths and the controversial Oscar nominee Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri; it is also more resonant, whether despite its narrowness or because of it.

Set in the (invented) titular isle off the coast of Ireland—the year is 1923, and the distant thud of cannon fire informs us of the civil war raging on the mainland—the movie chronicles the friendship between Pádraic (Farrell) and Colm (Gleeson), two bosom buddies who ritualistically visit the local pub whenever the clock strikes two. Or at least, they used to. In the opening scene, Pádraic (rhymes with “frolic”) discovers to his bafflement that Colm has no interest in joining him for a pint. And while he initially hopes that this sudden hostility is a temporary episode, that prospect is swiftly put to bed when Colm bluntly informs him, “I just don’t like ya no more.”

This level of forthrightness is atypical among adults of any demographic or locale, much less stoic men from a homey hamlet like Inisherin, and its candor sends Pádraic into an emotional and metaphysical tailspin. Did he do something wrong? Is Colm simply playing an April Fool’s prank? Can their camaraderie possibly be repaired? Has he misjudged the man who’s been his closest friend for ages?

As with Armageddon Time, The Banshees of Inisherin is rigorously committed to its specific setting—McDonagh populates the outpost with colorful barkeeps, gossips, and coppers, all of whom seem less like characters than creatures who sprang from Ireland’s soil—but its insights and explorations of male friendship aren’t confined to its own era. Virtually all relationships are asymmetrical to a certain degree, and a shift in the (im)balance always has the potential to cause confusion, awkwardness, or sorrow. (This happens to be the second picture in recent years to remind me of Seinfeld’s “Male Unbonding” episode.) But ghosting wasn’t an option a century ago, and so Colm resorts to more drastic measures: He vows that if Pádraic continues to associate with him, he’ll slice off one of his own fingers for each unwanted interaction.

The absurdity of this threat jerks The Banshees of Inisherin out of the genre of small-town comedy and places it into the realm of fable. How you respond to this tonal shift will likely hinge on your tolerance for thematic surrealism. But regardless of whether you accept the film’s outlandish premise, it seems impossible to deny the strength of McDonagh’s conviction—the way he fleshes out his bizarre setup with detail, compassion, and humor. Pádraic and Colm’s ensuing run-ins are bleakly funny—if nothing else, they afford Farrell the opportunity to mangle the pronunciation of Beethoven—even as they provoke sincere questions about the nature of their now-severed bond.

Just why were they friends in the first place? Besides living in the same town, they seem to have nothing in common, either professionally or temperamentally. Pádraic is a dim-witted dairy farmer whose closest companion, aside from his sister Siobhan (a wonderful Kerry Condon), is the miniature donkey whom he regularly invites to join him at the dinner table. Colm, by contrast, is an aesthete—a fiddle player (it’s unclear if he derives actual income from this) who has grown preoccupied with the notion of artistic legacy. His rationale for cruelly jettisoning the far nicer Pádraic is that he can’t waste his waning years on idle chitchat. “He’s dull,” Colm says to Siobhan of her brother, to which she replies, with delightful incredulity, “He’s always been dull!”

Maybe so. But Farrell nevertheless brings honor to Pádraic’s clumsiness, deftly articulating the severity of his wounds and the corresponding surge in his pride; he’s a smart actor who finds integrity in the role’s stupidity. For his part, Gleeson leverages his looming physique, even as he wisely recognizes that Colm is, so to speak, the picture’s second fiddle. (Having previously played a priest for McDonagh’s brother, John Michael, in Calvary, Gleeson here finds himself on the opposite side of the confessional, in a few poignant scenes that help bring dimension to a film that otherwise broadly adopts Pádraic’s point of view.)

And while The Banshees of Inisherin remains sharply focused on its feuding drunkards, McDonagh invisibly adds texture to it without cluttering his narrative with subplots. Siobhan, it’s plain, has a melancholy life of her own, and Condon effortlessly communicates the character’s intelligence while also supplying some belligerence of her own. (Upon realizing that the postmaster has snooped on one of her letters, she snarls, “Fell open, did it?”) And then there is Dominic, the village idiot played by Barry Keoghan who serves as both the movie’s holy fool and its moral conscience. His grubby circumstances and tragic fate help imbue the picture with an elegiac air that McDonagh boldly accentuates in its final scenes.

That those scenes are more thoughtful than wrenching is perhaps a limiting consequence of McDonagh’s allegorical style. Or maybe it’s of a piece with the movie’s surprising sensitivity—its caressing visuals (there are numerous gorgeous shots of Irish landscapes) and tender humanism. If Armageddon Time is clear-cut and Aftersun is impressionistic, The Banshees of Inisherin somehow manages to be both at once: a spiky, somber fairy tale that turns something as simple as friendship into an elusive mystery.

Grades

Armageddon Time: B-

Aftersun: B

The Banshees of Inisherin: B+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.