Can a Marvel movie be an underdog? Certainly not commercially; even before it smashed the November box office record with $181 million last weekend, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever was guaranteed to make an enormous amount of money. But artistically, Ryan Coogler’s sequel faces a set of challenges that are atypical to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, with its rigorous quality control and absurd phases and general regimentation. To begin with, his follow-up bears the weight of considerable expectations; in addition to banking $700 million—the third-highest of any film to that date (though it’s since been surpassed by Avengers: Endgame, Spider-Man: No Way Home, and Top Gun: Maverick)—the original Black Panther earned rave reviews and a rare sheen of prestige, racking up seven Oscar nominations (including Best Picture!) and taking home three statuettes. But beyond that, Coogler is faced with an even graver dilemma: that of making a Black Panther movie without the Black Panther.

Chadwick Boseman’s death two years ago was tragic for many reasons, most of which have nothing to do with corporate profits or franchise continuity. But viewing it purely (and perhaps distastefully) in the context of the MCU, it placed Coogler in a no-win situation: He could either recast the role of King T’Challa, thereby inviting unsavory comparisons and risking the wrath of countless fans, or he could kill off a beloved character and bake his demise into the sequel’s plot. (The prospect of simply not making a follow-up at all is too ludicrous to contemplate.) He chose the latter approach, and in case you were somehow oblivious to Marvel’s marketing machine, he announces his decision straightaway; the cold open of Wakanda Forever finds T’Challa’s younger sister, Shuri (Letitia Wright), frantically trying to wield her technological expertise to cure an unspecified illness, to no avail. Coogler stages this brisk prologue, which concludes with a mournful funeral procession, with the appropriate degree of sobriety—the shot of T’Challa’s coffin mystically ascending to an airborne vessel is heartrending, while the replacement of the standard Marvel logo (which typically affords glimpses of various MCU heroes) with exclusive footage of Boseman is a lovely touch—even as it shrouds the ensuing film in death.

Not that Wakanda Forever skimps on spectacle or clamor. Per his blockbuster imperative, Coogler ably (if somewhat dutifully) marshals the vast resources at his disposal and assembles them into a loud and boisterous production. There are colorful costumes, explosive gadgets, and exotic locales, in particular an underwater kingdom that undulates with its own mythical lore. All the same, the visual sparkle that accompanied our first journey to Wakanda has been supplanted by a more perfunctory busyness—the impression that Coogler is desperately hurling ideas at the screen (hey look, an Iron Man clone!) rather than shaping them with the proper polish.

That sense of clutter also applies to the film’s story, which again bristles with ostensibly interesting concepts—the fallacy of monarchal rule, the complexity of geopolitics, the dwindling of the planet’s natural resources—but struggles to harness them into a coherent throughline. Having previously disclosed its possession of the precious commodity vibranium to the United Nations, Wakanda finds itself the target of imperialistic envy and bigoted fearmongering. (A slyly cast Richard Schiff pops up as a mistrustful U.S. bureaucrat, doomsaying about weapons of mass destruction.) This potential for disaster grows thornier and graver with the (literal) emergence of the Talokanil, a race of water beings with access to their own deposit of vibranium, and who are led by a godlike figure named Namor (Tenoch Huerta Mejía). An early scene in which these blue-skinned nymphs lay waste to a surveilling party of Navy SEALs (hi Lake Bell! bye Lake Bell…) identifies them as antagonists, while Namor’s silkily worded threats to Shuri’s mother, Queen Ramonda (Angela Bassett, quite good), brands him as the movie’s chief villain.

As tends to be the case in Coogler’s films, things are a bit more complicated than that—or at least, they’re meant to be. Namor, with his delicate features and tragic backstory, isn’t a mustache-twirling megalomaniac so much as a concerned civic leader, anxious to preserve his people’s safety and autonomy. His militaristic instincts are designed to clash against the more pensive and diplomatic approach advocated by Shuri and Ramonda, who strive to honor T’Challa’s legacy by positioning Wakanda as a global power rather than a reclusive haven.

This dynamic essentially inverts the central conflict of the original, which found T’Challa preaching stoicism in the face of the bloodlust promoted by his vengeful cousin, Erik, aka Killmonger. And that highlights Wakanda Forever’s real problem. Boseman’s absence may cast an inevitable pall over the proceedings, but what the movie really misses—what no amount of tweaking or massaging can compensate for—is Michael B. Jordan. It was his mesmerizing performance as Killmonger that supplied the first Black Panther with its electric charge, its genuine danger, its seismic force. Huerta Mejía does his best, but his Namor can’t help but feel like a feeble imitation, which renders the character’s putative menace largely gestural.

It’s perhaps unfair to judge Wakanda Forever in comparative terms, given that equaling its predecessor’s combination of thought-provoking politics and rambunctious entertainment was always going to be daunting. But what’s really disappointing about the movie is how familiar it is—how it feels like just another installment rolled off the MCU merchandising line. Coogler still has a sure hand with actors, but his authorial personality now seems diminished. You can imagine the film’s predictable franchise signifiers—the stale banter, the green-screened action, the overlong climax, the same-sex kiss that lasts no longer than three milliseconds —as having been orchestrated by any studio journeyman.

It doesn’t help that Marvel’s house formula—a carefully calibrated mix of quippy comedy and chaotic, SFX-heavy set pieces—doesn’t play to Coogler’s strengths. The dialogue, which he wrote with Joe Robert Cole, is oddly stiff, especially when it tries to be light. The MCU has always been a deceptively productive comedy factory—the sweet-natured bickering of The Avengers, the playful one-upmanship of Guardians of the Galaxy—but the sequence where Shuri and Wakanda’s fearsome general, Okoye (Danai Gurira), travel to Harvard to recruit a brilliant student (Dominique Thorne) stumbles with flat jokes, forced laughter, and stilted rhythm. Even worse are the scenes featuring a wary CIA operative (Martin Freeman) and his duplicitous boss (Julia Louis-Dreyfus, still on autopilot), which yank the movie away from Wakanda and waste time integrating it into this entropically expanding franchise, only adding to the picture’s sense of bloat.

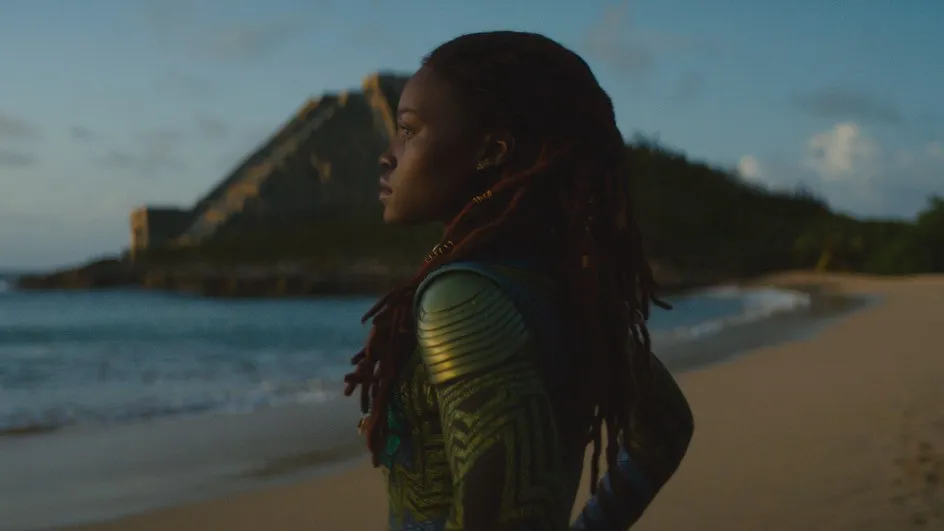

When it comes to action, Coogler fares little better. The early battles are darkly lit and sloppily choreographed (it doesn’t help that Namor’s soldiers feel like outcasts from the upcoming Avatar sequel), and while some of Okoye’s spear-wielding carries some zip, it can’t hope to match the visceral intensity of the cliffside duel between T’Challa and Killmonger. (Whoops, there I go again.) Over time, Coogler does brighten both the weather and his color palette, supplying a few striking images set in daylight; a nifty new armor called Midnight Angel glimmers with blue-and-gold trim (Michaela Coel has stepped in for Daniel Kaluuya as one of the kingdom’s chief enforcers), while the shot of red-robed Wakandan warriors charging vertically down a ship’s starboard is energizing. But Coogler still can’t solve Namor; as clumsy as the character is thematically, he’s an even less interesting combatant. With his winged feet and omnipotent weapons, he embodies all of the flaws of swollen CGI sensationalism: weightless, hectic, arbitrary.

The target of Namor’s wrath tends to be Shuri, and it must be said: Wright holds her own here. The young and wiry Briton surely never imagined, when she signed on six years ago as the seventh-billed actor in a superhero flick, that she’d soon be headlining one of the biggest movies ever made. But she cannily exploits her lack of stature, which features a sliver of meta recognition. Beyond her crippling grief, Shuri’s existential crisis lies in her fear that she can’t possibly fill the enormous void created by her brother’s death, and Wright—replacing a cherished star herself—conveys her angst through faltering facial expressions and tremulous body language. She and Bassett, who exudes icy regality with inveterate ease, provide the film with its quavering emotional resonance.

Which is fine, as far as it goes. Black Panther: Wakanda Forever isn’t a bad movie, just a predictable and typical one. Yet its ordinariness feels oddly dispiriting. If Ryan Coogler, who before making Black Panther revitalized the Rocky series with Creed, can’t turn a $250 million budget into an interesting superhero feature, who can? Perhaps this is simply what the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become. Shuri and Ramonda take the issue of Wakandan royal succession seriously, but at some point, it’s hard to shake the feeling that each new episode of this competent, compulsory franchise is just another pretender to the throne.

Grade: C+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.

Watched it yesterday and found it underwhelming, some individually good parts but messy and unsatisfying as a whole.

I found it very drab visually, night-time and underwater sequences were hard to make out clearly and even daylight scenes felt ‘muddy’ in places – possibly an issue with the particular screening I saw though?

I saw some rumblings on Twitter from people complaining about the lighting and wondering if it was poor projection quality. I was OK with the daylight scenes but found the early nighttime scenes far too dark. Hard to say whether that’s on the movie or the theater.