No cows fly in Twisters, but there’s still plenty of bullshit. Directed by Lee Isaac Chung from a script by Mark L. Smith, this muscular movie skillfully and predictably conjures devastating cyclones capable of demolishing entire towns, but the most powerful force on display is the manipulative currents of the screenplay. If you’re having trouble distinguishing between the heroes and the villains, just wait for the scene where an anxious storm chaser expresses concern for the people of a nearby hamlet, only for his companion to snarl in response, “I don’t care about the people!”

So no, Twisters, like its singular-titled 1996 predecessor (with which it shares a spiritual lineage but no narrative connection), is not a work of great subtlety. But it is nonetheless a competent blockbuster—generally diverting and sporadically delightful, with pleasant characters and robust spectacle. Even its emotional hackwork is often agreeable, thanks to the warmth and agility of its cast.

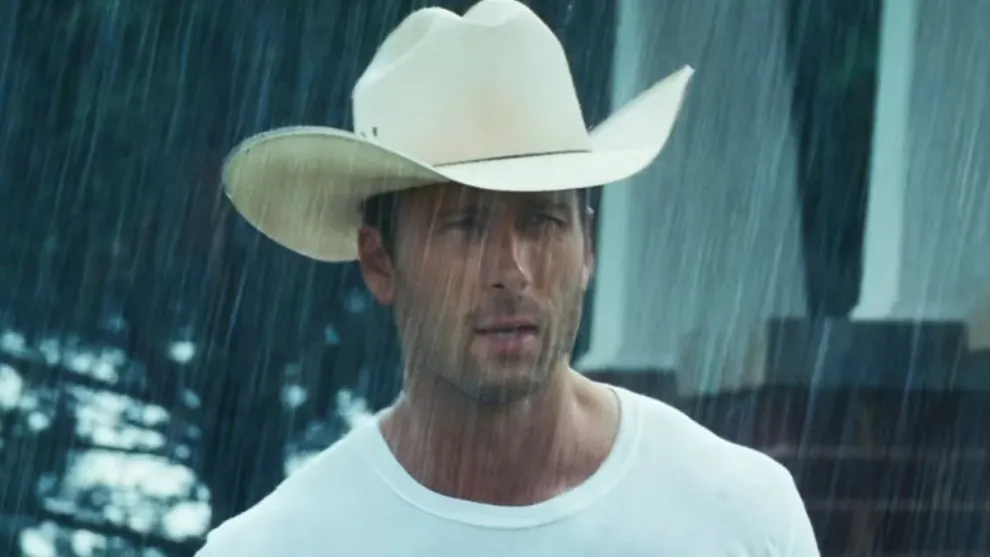

The most charismatic member of Twisters’ ensemble is Glen Powell, who continues in his ongoing coronation (following Hit Man, Anyone But You, and Top Gun: Maverick) as America’s next big movie star. He plays Tyler Owens, a swaggering “tornado wrangler” who’s less scientist than celebrity. Tyler doesn’t appear to be a man of much substance—whereas the film’s more putatively serious characters track cyclones with the goal of testing a reliable method of diminishing their potency, he’s more interested in whether you can blast fireworks inside their whirlwind—but he’s charming company, which explains why he and his crew of boisterous hotshots (including Brandon Perea and Sasha Lane) have acquired over a million YouTube followers. Surely the Stetson and the tight white T-shirt don’t hurt.

Tyler may be the embodiment of the movie’s jovial spirit, but he isn’t its main character. That would be Kate Carter (Daisy Edgar-Jones, very fine), who occupies a more conventional place on the heroic spectrum. Twisters was initially conceived by Top Gun: Maverick director Joseph Kosinski (he receives a story credit), and while Tom Cruise has unofficially anointed Powell as his heir apparent, it’s Kate’s arc here that oddly resembles that of Pete Mitchell in the first Top Gun. When we first meet her, she’s self-assured to the point of cockiness—a natural successor to Helen Hunt’s gung-ho storm chaser from the original. But following an early tragedy (which Chung stages with admirable efficiency), she loses both her nerve and her sense of purpose. (When we next see her, she’s relocated from the plains of Oklahoma to the high-rises of Manhattan and—in the ultimate symbol of cinematic cowardice—has traded in her dungarees for a smartly pressed suit.) In its bold strokes, Twisters is the story of Kate’s redemption: Recruited by an old colleague, Javi (a poorly served Anthony Ramos), for a one-week heartland homecoming in the midst of a tornado surge, she must rediscover her prior intuition and atone for her past mistakes.

On the page, such a journey might sound tedious or trite. But as she demonstrated in the goofily enjoyable Where the Crawdads Sing, Edgar-Jones has a talent for taking potentially risible material and investing it with emotional legitimacy. The scenes of Kate gradually getting her groove back—whether she’s anticipating a storm’s trajectory or just exchanging barbs with the perpetually smirking Tyler—are satisfying for the quiet way she reclaims a measure of her agency.

It’s a pity Edgar-Jones can’t salvage the entire screenplay, which for the most part is thuddingly obvious. (Such clumsiness is typical for Smith, whose recent scripts have ranged from curiously simplistic (The Revenant) to endearingly maudlin (The Midnight Sky) to straight-up awful (The Boys in the Boat).) It initially posits Tyler as a flamboyant loose cannon, as distinct from Javi’s more disciplined army of decorated academics, only to inevitably switch sides, revealing Tyler as a man of steadfast integrity and Javi as the compromised arm of a soulless corporate machine. The subplot in which a profiteer exploits the suffering of displaced residents is too clunky to acquire any resonance, making you long for the sneering villainy of Cary Elwes (or, to tack in the opposite direction, the thoughtfulness of Chung’s prior feature, Minari).

But so what? This is Twisters; we don’t care about the people, we’re here for the cataclysmic set pieces. And overall, the many sequences of pandemonium that populate the movie are… fine. They all tend to follow the same rudimentary pattern: Kate and Tyler spot a tornado, drive toward it—Kate so she can launch a thingamabob designed to weaken its destructive power, Tyler so he can do some cowboy shit on his live-stream—then speed away from it in a panic. (This model mimics Jan de Bont’s original; the chief new innovation here is Tyler’s spiral clamp that tunnels into the ground, the better to prevent his truck from being sent skyward.) The action scenes evoke the mirror bit from Jurassic Park, only instead of fleeing a T-Rex, our heroes are running from the weather.

This presents a challenge for Chung—not just because cyclones lack the snarling savagery of dinosaurs, but because their airborne nature makes it difficult to imbue them with visible weight. The special effects in Twisters are entirely credible—no specter of phoniness surrounds phenomena that were surely computer-generated—but there is only so much excitement to mine from people constantly hiding in shelters or clinging to objects. Chung delivers a handful of solid sequences—a relatively small-scale storm where rodeo onlookers pile into a motel pool, a climax where a movie theater becomes both haven and hot zone—but they lack the demented imagination of, say, Hunt and Bill Paxton driving through a flying house.

For a disaster picture about thrill-seeking tornado wranglers and catastrophic natural forces (the topic of climate change is alluded to but never directly addressed), Twisters operates with a paradoxical sense of caution—both in its modulated mayhem and in the slow-simmering chemistry between Edgar-Jones and Powell, which is never allowed to boil over into a bona fide romance. At the same time, the movie exhibits an appealing lightness that distinguishes it from the brawny, pushy blockbusters of its era. It may technically be a sequel, but it’s unburdened by franchise lore, and even if it’s nominally focused on providing heart-pounding bedlam, it also creates characters who are fun to be around. It takes you for an entertaining ride. It just never sweeps you away.

Grade: B-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.