Uncut Gems: Doubling Down, on Distress and Excess

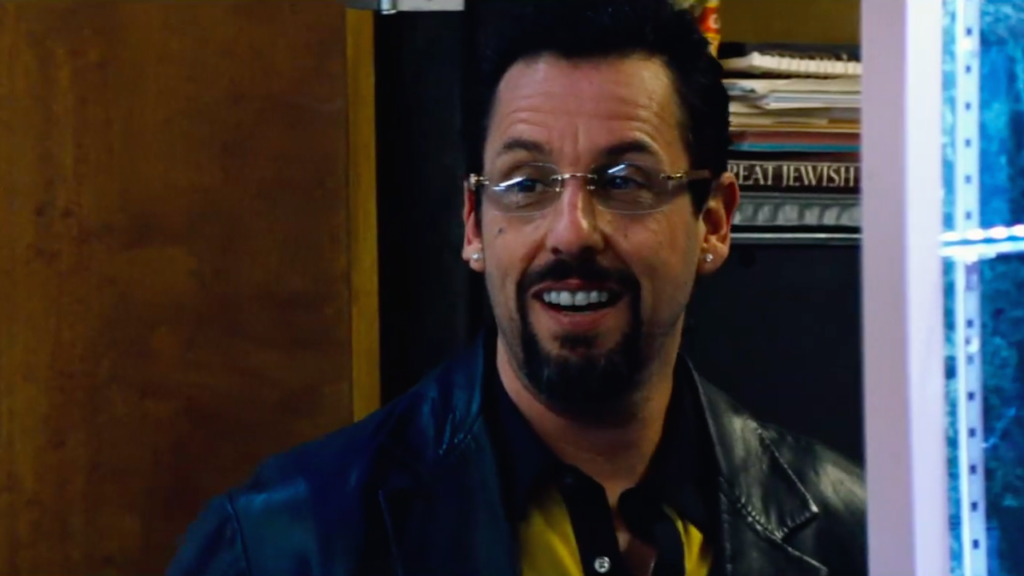

Of course Uncut Gems opens with an extreme close-up of a colonoscopy. After all, this nasty, edgy, oddly exhilarating movie is the work of Josh and Benny Safdie, those sibling purveyors of stomach-churning New York City sleaze. Their prior film, Good Time, steeped itself in grimy brutality, featuring all manner of crimes, deaths, and maulings. Their new picture, as its initial footage of a man’s digestive tract suggests, in no way eases up on the throttle; it’s another portrait of a desperate man, and it’s uncompromising in its vulgarity and intensity. Yet there’s something strange about Uncut Gems, something shiny buried within its crusty shell of unfiltered savagery and heedless aggression. It is—and I can’t believe I’m writing this, given that the Safdies’ filmmaking ethos seems to involve making the viewing experience as nauseating as possible—fun to watch.

Whether it’s pleasant to look at is another matter. With each new feature—before Good Time, they made the low-budget addiction drama Heaven Knows What, starring mostly non-professional actors—the Safdies grow increasingly accomplished in refining their distinctive style. It is not an aesthetic I particularly care for. The camera is wobbly, the music (again by Daniel Lopatin, aka Oneohtrix Point Never) is invasive, and the lighting is, well, not very light; many scenes play out in dim interiors, with unflattering illumination that makes the actors look wan. Occasionally, they subvert their grungy approach in productive ways, such as when a musician activates a black light at a nightclub, suddenly brightening the screen with bolts of neon. The veteran cinematographer, Darius Khondji, has worked with David Fincher, Bong Joon-ho, and Michael Haneke, and he helps modulate the Safdies’ signature freneticism with a measure of discipline. Still, for the most part, this movie looks gritty, sickly, and ugly. Read More