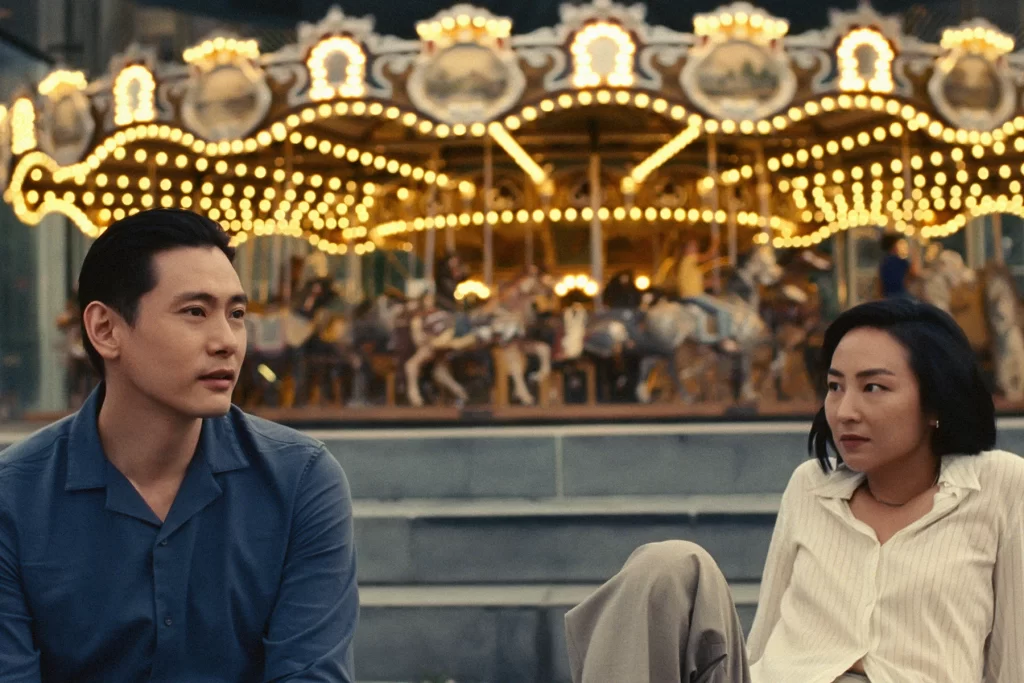

Past Lives: No Sublime Like the Present

Late at night in a Manhattan bar, we see three people: an Asian woman seated in between two men (one white, the other Asian). They’re chatting amiably, but we can’t hear what they’re saying; instead, we listen to the observations of an unseen couple who speculate about the triad’s possible relationships. Perhaps two of them are married and the other man is her brother, they suggest, or maybe the white guy is an American tour guide. As they conjecture, the woman turns her head and looks directly into the camera, her eyes both inviting and comprehending of our attentions, as though she’s slyly caught us in the act.

This is the opening scene of Past Lives, the debut feature of writer-director Celine Song, and it immediately signals the film’s rare, delicate intimacy. When you buy a ticket for Past Lives, you end up not so much watching a movie as participating in an act of eavesdropping. Sure, you’re seeing actors pantomime a fictional story of love and loss, but you are also receiving an unauthorized glimpse into the inner worlds of two people—a secret chance to understand their desires and bear witness to their heartbreak. Read More