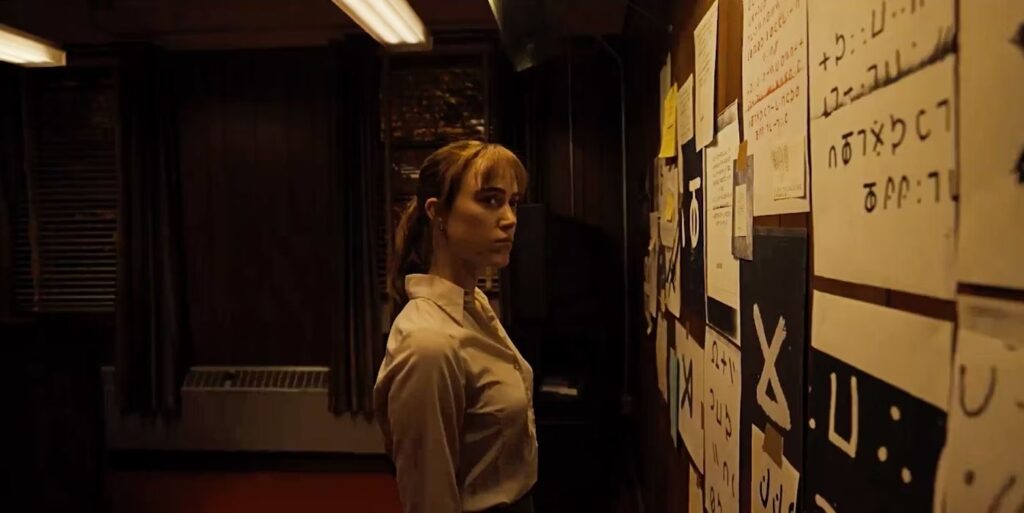

Blink Twice, Strange Darling, and the Third-Act Problem

Movies are built for catharsis. Regardless of genre—the romantic comedy’s race through the airport, the murder mystery’s unmasking of the killer, the sports picture’s big game—cinematic endings are designed to cash the checks that their films have spent the past two acts writing. The paradox of this construction, at least when it comes to the modern thriller, is that most directors are more skilled at building tension than unleashing bedlam. Auteurs such as Ari Aster, Osgood Perkins, and M. Night Shyamalan (to name a few) are all capable craftsmen, wielding their razor-sharp technique to amplify our unease, but while they’re skilled at manufacturing suspense, they often struggle to pay it off in ways that are genuinely unpredictable or exciting.

Last weekend saw two new releases acutely vulnerable to this common pitfall. One tumbles into it. The other does its best to evade it, partly by rewiring its chronology. At the risk of evoking that head-tapping “Roll Safe” meme, your third act can’t ruin your movie’s ending if it arrives in the first 15 minutes. Read More