Sully: He’s Not a Hero. Just Ask the Government.

In the dreadful 2012 flop Trouble with the Curve, Clint Eastwood plays a grizzled baseball scout who has grown disgusted with the sport’s increasing reliance on analytics and technology. “Anybody who uses computers doesn’t know a damn thing about this game,” he growls at one point. His irascible critique encapsulates the film’s worldview, namely, that the classicist’s wisdom of observational experience will always vanquish the modernist’s reliance on statistical data. That broad thesis is now the animating force behind Sully, Eastwood’s brisk, hackneyed, intermittently diverting reenactment of an American tragedy that wasn’t. It’s the kind of movie where the officious villains blindly trust computer simulations, only to be taken aback when they’re informed that they’ve failed to account for that most vexing of variables: humanity.

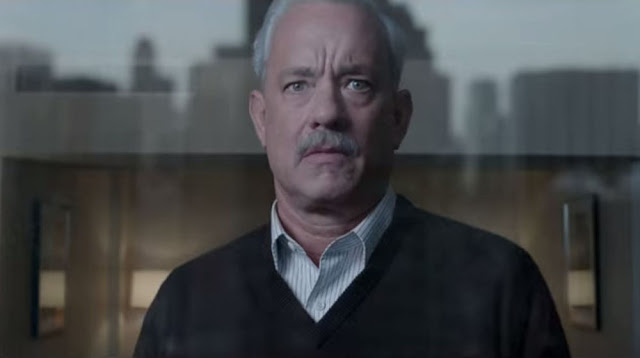

The majority of the humanity in Sully derives from Tom Hanks, an actor who, luckily for Eastwood, could imbue a paperclip with an aura of moral and professional authority. Here he provides the necessary blunt-force gravitas as Capt. Chesley Sullenberger, the pilot better known as, well, you know. The film opens with anonymous voices screaming Sully’s name as an airplane glides above the streets of Queens before crashing into a skyscraper. It’s a nightmarish image, which makes sense, given that it is born from Sully’s nightmares. In actuality, as you will no doubt remember, things went quite differently: On January 15, 2009, after U.S. Airways Flight 1549 suffered power failure in both engines due to bird strikes, Sully successfully landed the plane on the Hudson River, saving the lives of all 155 souls on board. The incident was swiftly dubbed “the Miracle on the Hudson”, with Sully as its chief architect. Roll credits. Read More