The Black Phone: No Answer, Try His Hell

Listen up, kids, here are some dos and don’ts courtesy of The Black Phone, the grimy new horror movie from Scott Derrickson: Do stand up to bullies by hitting them in the head with rocks. Don’t beat your children with a belt, even if you’re really just a sad dad on the inside. Do pay careful attention to your dreams, which may or may not be premonitions. Don’t invite the cops inside your home while lines of cocaine are visible on your coffee table. And if a dude in clown makeup driving a black van branded “Abracadabra” approaches you on a vacant sidewalk, do immediately walk the other way; don’t—seriously, do not—ask if you can see a magic trick.

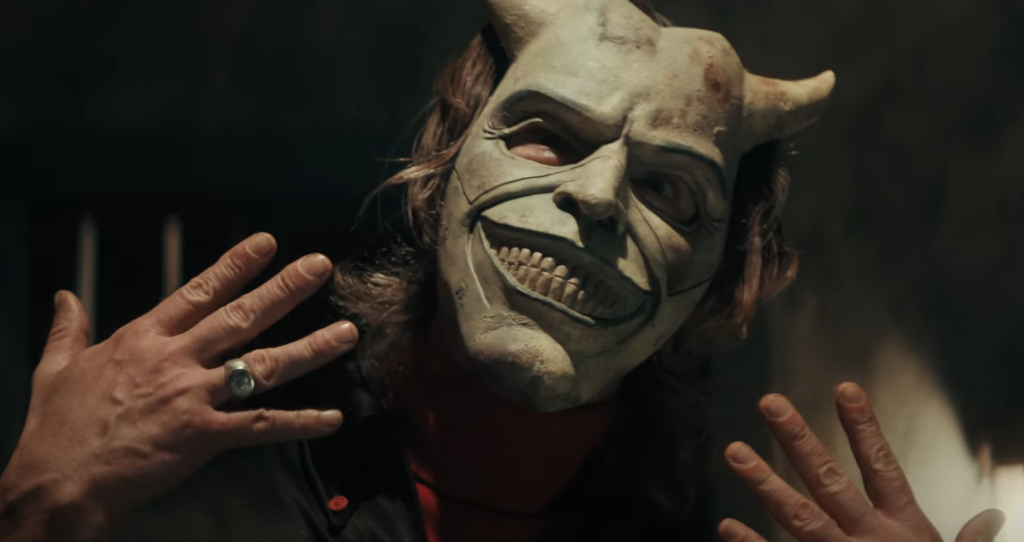

That last nugget comes courtesy of The Grabber, a serial killer terrorizing a morose Denver neighborhood in 1978. With lank hair and dark eyes that peek out from behind a two-piece mask—the upper part topped with devilish horns, the lower forming a demented smile—he’s played by Ethan Hawke, continuing the actor’s not-unwelcome veer into villainy following his small-screen turn on Marvel’s Moon Knight. There are moments of real menace in Hawke’s performance here; when he smothers a child’s cries and threatens to gut him like a pig before strangling him with his own intestines, you know he means it. For the most part, though, he keeps things in second gear, gesturing toward evil rather than embodying it. Read More